An Interview with Paul Vermeersch

By James Lindsay

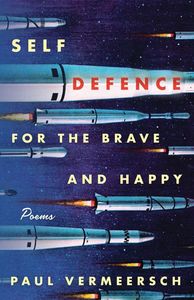

Self-Defense for the Brave and Happy, the sixth collection by poet, professor, artist and editor. Paul Vermeersch, feels like a flashlight found in a blackout. By his own admission, when writing the poems, “the themes and subjects were as dark as ever,” but now there was also a playful optimism in tow, one he discovered while returning to visual art, and when he began to write these poems, “that playful tone stuck.“ This is a sort of mischievous hopefulness in its ability to envision a utopianism that could be viewed as naïve by a cynical gaze. But why is it naïve to imagine something better than now? And how and when did we as a culture lose our desire to believe in a better world? In an indirect way Self-Defense for the Brave and Happy ask these questions, but, more so, it strives to give practical examples of better dreaming for the future.

James Lindsay:

Self-Defense for the Brave and Happy begins with an epigraph from Jane Jacobs that I’d like to quote here in full because I think it’s indicative of where your work has progressed over the years. “Being human is itself difficult, and therefore all kinds of settlements (except dream cities) have problems.” Your poetry has always struck me as having a deeply humanistic quality to it, but recently it has also taken on futuristic aspects that hint at something like a utopia, a better place than where we are now. Is this an accurate assessment of your poetry? How do see futurism and utopia playing into it?

Paul Vermeersch:

Ah, the world of tomorrow! I admit to having real nostalgia for the optimistic futurism of the Space Age: the world envisioned -- in the popular imagination -- by people like Buckminster Fuller, Walt Disney, Carl Sagan, and Gene Roddenberry: the jet packs, commuter rails and fantastic buildings of a post-capitalist utopia built on the principles of scientific and intellectual discovery. Are these are the dream cities that Jane Jacobs alludes to? I don’t so much long for those dream cities, though, as a time when people believed they were possible. I was born and came of age when the Space Age was already experiencing its downturn, and for the majority of my life, it seems like the dominant mode of imaginative futurism has been the dystopia -- from Mad Max to Blade Runner to The Handmaid’s Tale. We’re far more captivated, it seems to me, by humanity’s capacity for self-destruction, and I have to wonder if our appetite for cautionary tales, rather than aspirational ones, is a symptom of widespread societal regression or one of its causes. I’m haunted by the question: if we spent more time imagining a better world, would we eventually achieve one? It’s this tension between hope and setback that’s at the heart of my new book, I think -- looking toward the dream city while standing in the wasteland, uncertain if the dream city is real or just an image on a billboard.

JL:

The examples you give (Mad Max, Blade Runner, The Handmaid’s Tale) are all from the late ‘70s to mid ‘80s. What do you think contributed to the rise of dystopianism and the down turn of the Silver Age in culture around this time? I even think of another movie from that period, Alien, and how all the technology in it seems so cold and anti-human: keyboards and DOS-like computers (as if we couldn’t believe science would progress much farther from where it was); killer androids whose only loyalty is for a faceless corporation. Even the idea of extraterrestrial life becomes threatening and unknowable. This all seems so far removed from, say, Star Trek, where technology and politics are presented as something that could be humanity’s salvation.

PV:

What turns the Enterprise into the Nostromo, Tomorrowland into Fury Road, hope into nihilism? What turns idealistic flower children into self-centered yuppies? Are the answers to be found in Billy Joel’s hand-wringing anthem “We Didn’t Start the Fire?” The Cold War, McCarthyism, the JFK assassination, Nixon’s corruption, Viet Nam, Reaganomics, terrorism? Did these traumatic experiences disabuse our elders of their visions of a better tomorrow, or are these just more symptoms of some larger, unseen disorder? Somehow the idea that society is a cooperative endeavour has been supplanted by the idea that it is a competition, a garish game show, Richard Bachman’s The Running Man remade again and again.

The dystopian stories we enjoy may be written as cautionary tales, as reflections of rational fears and anxieties, but more and more they are presented to us -- or sold to us -- as inevitabilities, as models of our possible futures or instructions for hopelessness. We don’t imagine forging pan-galactic alliances with alien lifeforms as much as we imagine shadowy agents rounding them up for dissection or weaponization. As these ideas become entrenched, it gets more and more difficult to imagine universal altruism. I suspect that those who seek to enrich and empower themselves at society’s expense, who view other people as an exploitable resource rather than as fellow citizens, prefer it this way. Is it too far-fetched to suspect there might have been some political will, some mobilization of resources, behind this shift in the zeitgeist? I find the prospect rather easy to imagine.

JL:

So much of Self-Defense for the Brave and Happy seems for be a rallying cry against, “those who seek to enrich and empower themselves at society’s expense,” but by way of uplifting and motivating instead of attacking. The title poem in particular--with its surreal instructions to not despair in the face of oppression--seems so tender in its coaching. Did you have a particular reader or audience in mind when writing these poems?

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

PV:

There are a few moments in the book where I want to walk the line between the necessity for self-care and the absurdity of the self-care industry. The title poem is one of them. “Being human is itself difficult,” says Jane Jacobs, and naturally people will want to seek whatever help they can get. Enter the snake oil salesmen, the advice columnists, the wellness gurus, the motivational speakers, the lifestyle bloggers, the brand influencers, the conspiracy theorists and preachers of every stripe. Claiming to have the answers can be very profitable. The poems in this book offer, as you have pointed out, surreal instructions or irrational suggestions. As answers, as advice, they’re useless, but I think they offer something else. “Poetry is useful, in fact crucial, in its uselessness,” says A. F. Moritz, and he’s really onto something. I think the imagination is one of the best tools we have for defending ourselves against the rising tide of hopelessness we’re being conditioned to accept. We don’t have to accept it. We can imagine something better, or at least something less harmful. Poetry, in its crucial uselessness, without an intrinsic need to be anything else, is an ideal framework for enacting that imagination.

JL:

Maybe more so than your previous collections, Self-Defense has a playfulness to it. I’m thinking of the visual poems in particular here, but there’s often humor throughout the book poems. It reminds me of your affinity for things like toy laser guns, kitsch, and the band Devo. Why did you include droll visual poems this time around and what does humor and playfulness in poetry mean to you?

PV:

I used to make a lot of visual art in my early twenties, but I gave it up when I started concentrating on my writing. I didn’t make any visual art for fourteen years, but in 2014 I found a cookie tin full of oil paints at a garage sale in Collingwood while visiting my mother. I estimate there was about $400 worth of paint in that tin, and the seller only wanted a toonie for it. Two bucks! The timing was fortunate. I had just released my previous book Don’t Let It End Like This Tell Them I Said Something, and I needed to take a few months off from writing to clear my head. Now here were these paints! I went back to making visual art with a vengeance: oil paints, oil markers, acrylics, brush pens, iron-on transfers, mixed media, you name it. What I found was that my visual sensibilities seemed to be naturally more playful than the somber tone that had evolved in my writing. I think that playful tone started to show itself in Don’t Let It End Like This Tell Them I Said Something, but the visual art I’ve been making took that aesthetic much further. I found that when I returned to writing the material that’s in Self-Defense for the Brave and Happy, even though the themes and subjects were as dark as ever, that playful tone stuck. The humour is rooted in this tone, in the clash between high and low culture, or between dire subject matter and an apparently carefree or oblivious speaker. And then there’s Saint Bigfoot. A few years ago I started a conceptual art project, a satirical religion called The Holy Order of the Sasquatch that combines writing and visual work. Over the past few years I began to see my writing and visual art not as separate pursuits, but as part of a continuum of multimedia work. Ultimately, it just made sense to include some graphic pieces in the new book.

JL:

Over the years you’ve acted as an editor and mentor to many poets and writers (myself included) through your previous work at Insomniac Press and now your Buckrider Books imprint at Wolsak and Wynn, and also as a professor and creative writing instructor. How do you see your role as editor opposed to poet? And how do you feel about being a mentor; someone who reaches out to offer support and guidance and direction?

PV:

For me, all of those things -- writing, editing, teaching and mentoring -- are part of the same job, part of being a poet. I am extremely fortunate to have had great mentors and teachers in my life, and wonderful colleagues and coworkers, and terrific students. I learn from all of them. I believe very much in the value of community engagement in the arts, and I think anyone’s creativity benefits from other people. We learn from each other. We teach each other. I know that every time I workshop or edit someone else’s writing, every time I prepare a lesson, every time I read and think about someone else’s work, I learn something new, something I can apply to my own writing, or to my editing or my teaching. It’s all connected. We make art, and we share art, and we nurture one another. This is how we build our own dream cities, how we populate them, how we care for our people.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

James Lindsay has been a bookseller for more than a decade. He is also co-owner of Pleasence Records in Toronto, a record label specializing in post-punk, odd-pop and avant-garde sound pieces.