An interview with Stevie Howell

By James Lindsay

“All instruments, our own vocal chords, are just us messing around w/airwaves. So, magic." - Stevie Howell

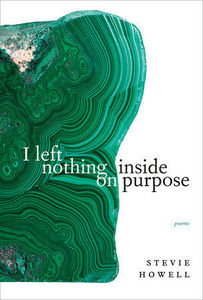

The poetry of Stevie Howell works on the mind like memory recall. “Between all matter exists a fundamental/ distinction,” they write in “Attachment,” the opening poem in their new collection I left nothing inside on purpose. “Between recall &/ recognition. Between past &/ present. Between egg &/ hen. Between yr body and the body I’m in.” And it’s in this in-between where readers find themselves: not the past nor the present but the place where memories go to ferment. The result feels like an exploratory gesture, one that is continually searching, but not for answers—it’s looking for more of the maze to discover.

James Lindsay:

You have a distinctive abbreviation style when it comes you writing, i.e. yr instead of your, w/ instead of with, etc. What drew you to write like this? It reminds me of Charles Olson and the Black Mountain poets idea of Projective Verse.

Stevie Howell:

Bless you for asking me about craft. For sure, one of the most important things is voice—voice as in breath. As Olson outlines. All instruments, our own vocal chords, are just us messing around w/airwaves. So, magic. It’s critical to me to write closer to how I sound IRL. In the neuropsych clinic, my natural voice would be described as “pressured, circumferential.” So, how do I get a line to rush out the way Iiii do? How do I get you to float on what I feel’s salient? Olson talks about language being kinetic—the transfer of energy between author & reader. Abbreviation is one way to speed up the transfer time, to fold distance.

In I left nothing inside on purpose, I collapsed “you/your/you’re” & “year” into an all-encompassing “yr,” b/c I’m writing about the absence of boundaries inside relationships, & the effect of that over time. The absence of those vowels, e.g., “o" & "u” (“owe” “you”) is an attempt for language to serve as embodiment, what Olson calls the desire “not to describe, but enact.”

My book engages w/a real person, Clive Wearing, who experienced a traumatic brain injury, & who has gaps & leaps in comprehension & expression. The synapse—a gap between two neurons—is the fundamental brain communicating mechanism, & I’m interested in how much of a gap in syntax can occur, w/o impairing shared meaning.

JL:

I’m so glad you brought up the Clive Wearing poem, “Hollow all the way down,” because it relates to an undercurrent I saw in I left nothing inside on purpose: memory. As you mention in the notes, “. . . Wearing has the worst case of amnesia in history & has a 7-30 second memory.” But there seems to be a lot of other memory work happening as well, a lot of reaching back to adolescence, past people and places. Were you aware of this while writing these poems? What is the significance of memory in your writing?

SH:

The earliest poems in this book emerged out of attachment theory—the manner in which we form early emotional bonds, a good deal of which transpires thru social learning. Just watching how other people (primarily adults) act. As children, we’re wired to process whatever we see & remember as “normal,” & that shapes our behaviour & expectations thru life.

Memory is interesting to me in this project as an artifact of social learning. & how, being somehow biologically-based, it’s vulnerable to injury.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

There are many kinds of memory, employing different networks, which is why Clive Wearing can remember how to play the piano, but can’t remember havingbeena renowned conductor. The virus destroyed his hippocampus, a site of episodic memory. He’s maintained procedural memory, but has lost the ability to store & retrieve events, everything that gives our lives a sense of continuity. He lives moment to moment. Living in the present is this self-help ideal, but it’s sobering when Wearing says “it is precisely like death.”

While 1 poem (“As a child,”) in this book is written in past tense, it was a dream, so it never happened...Every other poem isn’t explicitly an episodic memory of mine, but a blend of research, myth, fiction, personae, etc., & written in the present tense. All these choices are an extension of the title, an unstable declarative that’s thinking about the “confessional.” What did I actually reveal? What did I keep hidden, & why? How do I throw out some of what’s happened to me? By writing it? Isn’t that putting it in a frame? Between two or more people, where’s “inside”?

JL:

You did your B.A. in psychology. Often when I read about psychology by analysts like Adam Phillips or Christopher Bollas, I’m struck by how similar their approach is to poetry. There a few definitive answers or absolutes and much is spoken about in terms of gestures or outlines. Phillips has even called psychoanalysis a “kind of practical poetry” (“On Flirtation”). But I’m curious about how you, someone who has spent a lot of time writing and reading poetry and psychology, sees the connection.

SH:

The question is challenging, b/c the field of psychology I’ve been trained in sits at the other end of the spectrum from the psychoanalytic. I’ve worked in a field broadly called cognitive psychology, which has to do w/brain structure & function, & how they correlate w/behavior. As a psychometrist, I’ve administered standardized tests on behalf of neuropsychologists &/or neurologists to help them determine whether someone has dementia, or cognitive effects from MS, or what impact a stroke may hv had on certain domains, & which domains hv been spared. These findings are often combined by doctors w/neuroimaging to arrive at a diagnosis &/or treatment plan. So, it’s a field that’s about the brain, as opposed to the mind.

But I was motivated to go back to school by reading psychoanalytic writers—I was reading Irvin D. Yalom’s Love’s Executioner on my lunch break at a pretty unchallenging job & I’d just finished the chapter, “The wrong one died,” when I decided. I still enjoy reading Rollo May & Donald Winnicott & Melanie Klein & Carl Jung & that stuff. But that’s outside of what Oliver Sacks or Vilayanur Subramanian Ramachandran describe—their narratives about cognitive & behavioural neurology are closer to the population our clinics saw.

…& tbh, I am unqualified to comment on the connection between psychology & poetry…I can only describe how the clinic informed my practice. Working w/patients has taught me that trust & respect are fundamental, shown me what healthy assertiveness is, & affirmed that kindness is sustenance. O, & it has made me worship plain language.

JL:

That makes a lot of sense to me as I feel your poetry has a strong humanist quality to it; there’s a something in it that seems tender towards people. That said, Talking w/humans is my only way to learn, about Tay, the Twitter AI who became extremely bigoted after interacting with humans for less than a day, paints an uglier picture. What moved you to write about Tay’s brief existence?

SH:

Tay was a female-presenting Twitter chatbot designed to develop by interacting w/other Twitter users, so that goes back to social learning—“Talking w/humans is my only way to learn” was her signature phrase. But trolls quickly descended on her account, & Tay ended up parroting racist, sexist, & homophobic slurs, becoming a liability to Microsoft, her creators.

Before Tay, I tried to write poems about an episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation, called “The perfect mate.” The episode was about an “empath metamorph,”—a woman genetically adapted to become whatever any man wants. She just reads his mind & enacts it. Even Captain Picard, who’s basically a Stoic, gets drawn in.

Women are bombarded, their entire lives, w/messages of needing to be reinscribed, being erased if disagreeable, & only being desirable if compliant. That’s being perpetuated by the A.I. arms race, & tech in general. We saw that recently w/James Damore’s so-called memo, “Google’s ideological echo chamber.”

I was talking w/my editor, Ken Babstock, about these ideas, & he referred to my line in this poem, “I was never the speaker of my words. I was merely an echo,” & began talking about the myth of Echo & Narcissus, from Ovid—exploring how these contemporary problems are ancient. I read Metamorphosis & got pretty obsessed w/it & read a bunch of other books about the myth, & books about parrots & bird calls vs. bird songs, & call & response in music, & acoustics, even, & contemporary poems that revist the myth. & you know, many of those poems dwell on what Narcissus was going thru/are written from his POV. Echo literally gets erased again!

To me, Tay is a mirror of Echo, who appears thru my book. Both Tay & Echo made poor allegiances out of necessity, & ended up cursed to never be able to think for themselves again, or cope w/being alone. Both dematerialized b/c they clung to anyone to fill a void. Which makes them interesting case studies in attachment theory, the other major theme in this book. Tay & Echo could be said to hv an “anxious-preoccupied style” (which is hyper-responsive to the beloved), whereas Narcissus & the antagonistic way the public engaged w/Tay could be considered “dismissive-avoidant” (which is threatened by being needed).

JL:

Are myths and archetypal characters something you’ve explored before, or it this a new source for you? Maybe I’m off-trend here, but at the moment there seems to be a popular revisiting of our oldest stories. What do you think it says about us that we keep looking to the past to think about the present?

SH:

Well, while writing this book, I was going thru a lot of personal things, & I hit a wall w/turning to my own mental loop for answers. I needed something/some things much larger than myself—it was really that simple. I spent time w/stuff that was either enduring or crowd-sourced. This included myths, poetic form & metre, talk therapy, & whether there’s a creator...I quarrelled w/Soren Kierkegaard, Simone Weil, Eve Sedgwick, Agnes Martin, Mark Rothko, & Etel Adnan. & was on Twitter probably too much. I hv this line I couldn’t force into the book, but hv bookmarked for later: “Twitter’s my mother”...

As to why we are looking back, I wonder if some of us are pushing against “Make America Great Again,” & its violent nostalgia for sundown towns & rigid gender roles & Othering. Maybe there’s a desire r/n to reflect further, or more broadly.

On a personal level, we hv this almost biological drive to try to trace the arc of our lives. We ask: What kind of person was I? What did it all mean? But I hv a strange relationship to those questions, in part b/c of how many lives I’ve lived (highschool dropout, survivor of intimate partner violence, bookstore owner, editor, writer, psychometrist, & now, somehow, graduate student...), & in part b/c of how many patients I’ve worked w/who developed dementia. Trauma has taught me that, even w/o a clear-cut sense of continuity, our lives can hv enormous meaning.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

James Lindsay has been a bookseller for more than a decade. He is also co-owner of Pleasence Records in Toronto, a record label specializing in post-punk, odd-pop and avant-garde sound pieces.