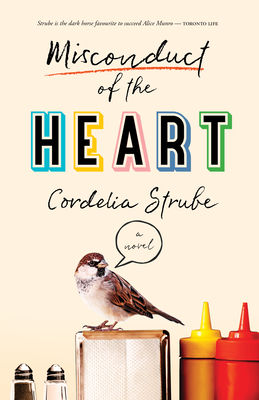

Book Therapy: Cordelia Strube’s Misconduct of the Heart

By Stacey May Fowles

“I so wanted things to be normal.”

“They can’t be normal. Make a new normal.”

—Cordelia Strube, Misconduct of the Heart

From the moment we went into isolation, people were making jokes. I don’t mean they weren’t taking things seriously (although there was certainly some of that too.) I mean that people had an amazing ability to find the salve of humour in the horror of a global pandemic. Despite the surreal nature of our experience, despite being mostly stuck inside our homes struggling to find information, food, and toilet paper, we were buoyed by a light-hearted joke tossed between friends—even if those jokes weren’t actually told in person.

Shared videos on social media of people passing time by pillow fighting in backwards hoodies. Neighbours playing ping pong with each other from across their balconies. Messy-haired shut-ins mocking the fact that they switched out of their day pyjamas into their night pyjamas. People riffing daily on their own increasing stir crazy-ness.

When I think about it, the ability to have a laugh when things feel dire is one of my favourite human traits. I tend surround myself with people who have a real gift for dark humour—they know that groping for levity in tragedy is what keeps us from descending into total darkness. They know that almost every crisis, personal or wide-scale, can be endured via a joke or two. They know that an inappropriate chuckle has the power to break through an otherwise insurmountable amount of tension.They have gotten me through a lot of bleak days.

“We’re sharing a joke that no one else finds funny,” writes Cordelia Strube of this brand of humour in her new novel, Misconduct of the Heart. “We are the naughty kids at the back of the class, delighting in our shared naughtiness.”

***

I had intended to read Misconduct of the Heart while on a long overdue vacation, preferably in the sun, on a reclining chair, while clutching a can of beer. It seems silly—even distasteful—to complain about the fact that this never actually happened. Our family trip to Florida was cut short when the Prime Minister stepped up to his podium and urged Canadians abroad to return home as soon as possible. My family was lucky enough to find a flight within twenty-four hours of his announcement and, while seated amongst panicked airline passengers in masks and gloves, Misconduct of the Heart remained unopened in my luggage.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

When I did get back to Toronto, buckling down for the required fourteen days of travel-related self-isolation, I could barely focus long enough to read a single page. As I worried about how we were going to get prescriptions, groceries, dog and cat food, I kept opening books and then abandoning them. I carried them from room to room, hoping they would somehow maintain my attention. What did get most of my attention was my phone, poisoning any chance of mental wellness with its relentless river of terrifying updates.

Even though I knew it would have been much healthier to even briefly escape into a novel, I couldn’t maintain focus long enough to get away from reality. I couldn’t stop myself from scrolling, clicking, and refreshing into oblivion. As one by one my favourite bookstores closed indefinitely, I couldn’t finish a chapter without at least a dozen self-imposed interruptions (and then a session of mentally punishing myself for said interruptions.)

Eventually I read a page here, and a page there, until I’d read a dozen. And then fifty. And then a hundred. I was grateful the book was there, even if I couldn’t give it the attention it deserved. It took me a full fourteen days of travel-related isolation to finish Misconduct of the Heart, in no way a comment on the book’s quality. Despite my pandemic-related personal reading failures, I was very glad and very grateful, in those difficult moments, to have a story of people surviving the worst by laughing their way through it by my side.

***

The cover copy of Misconduct of the Heart includes words like “hilarious” and “darkly humorous,” and claims it “will make you cheer.” It’s also a book about the unspeakable violence of war, PTSD, rape, abuse, neglect, poverty, racism, alcoholism, cancer, suicide, mental illness, and the exploitative nature of capitalism. It’s an onslaught of difficult issues and horrifying experiences, a depiction of damaged people who have lived through the worst, and who are punishing each other as a result. But it’s also a book that proves this kind of gruelling subject matter is not incongruous to laughter, and that suggests finding levity may be the only way to get through.

Stevie is a recovering alcoholic who lives with her veteran son, struggling under the weight of both his PTSD and her own. She is a survivor of gang rape, and her son—also an alcoholic—is unaware that is how she became pregnant with him. Stevie’s parents are mentally deteriorating, her gruelling kitchen job is in daily chaos and threatened by corporate “restructuring,” and her closest confidants face discrimination, violence, infidelity, and cancer, among other things. A blind geriatric dog ends up in her care, and a little girl who may or may not be her granddaughter, and may or may not have been abused, shows up on her doorstep; “She is so small, so mighty, so weary, so wise. She has remained her singular self due to sheer force of will, despite neglect, abandonment, burns.”

And yet, with all of this, the book is darkly funny, even heartwarming. It is real, and raw, and jarring, and frenetic, and upsetting—but it is also about people being deeply loyal, and showing up for each other. It is about them loving one another despite not knowing how to love. It’s about them throwing up their hands and simply coping with what is directly in front of them in whatever way they can. It is about how mundane struggle and suffering can actually be, and how in the end all we can really do is move forward with our circumstances in the hope of something better.

“(A)ll the stuff between birth and death feels random. We thrash about trying to find a reason for it, a logic. Why? All the things that happen, or almost happen, or never happen, make us who we are.”

***

The human capacity to find joy in difficult times has been proven to me over and over again during the last few weeks. Even as the news got worse, the restrictions tighter, the timeline longer, and our fears heightened, there has been a great deal of gratitude, resilience, and reprieve found in laughter between loved ones. I’ve been grateful every time I’ve heard it, and welcomed the escape whenever it was my own.

Making people laugh during times like this is a gift, and it is one that Strube’s admirable Stevie has mastered. Even if that laughter is used as a way to deflect, or to look away, or to temporarily avoid the real work of healing from trauma, it’s unbelievably necessary in the space between. In Stevie’s case, laughter and keeping things light helps her arrive at the kind of love she didn’t know she was allowed to have, and keeps her and the people she cares about alive.

It’s true that certain human coping mechanisms may not be pretty, or sanctioned, or even “tasteful”—but if they bring people together and help them survive the worst, they can certainly be valuable. There is nothing funny about what we are all dealing with right now, but shared laughter may be the only way we’ll cope.

Book Therapy is a monthly column about how books have the capacity to help, heal, and change our lives for the better.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Stacey May Fowles is an award-winning journalist, novelist, and essayist whose bylines include The Globe and Mail, The National Post, BuzzFeed, Elle, Toronto Life, The Walrus, Vice, Hazlitt, Quill and Quire, and others. She is the author of the bestselling non-fiction collection Baseball Life Advice (McClelland and Stewart), and the co-editor of the recent anthology Whatever Gets You Through (Greystone).