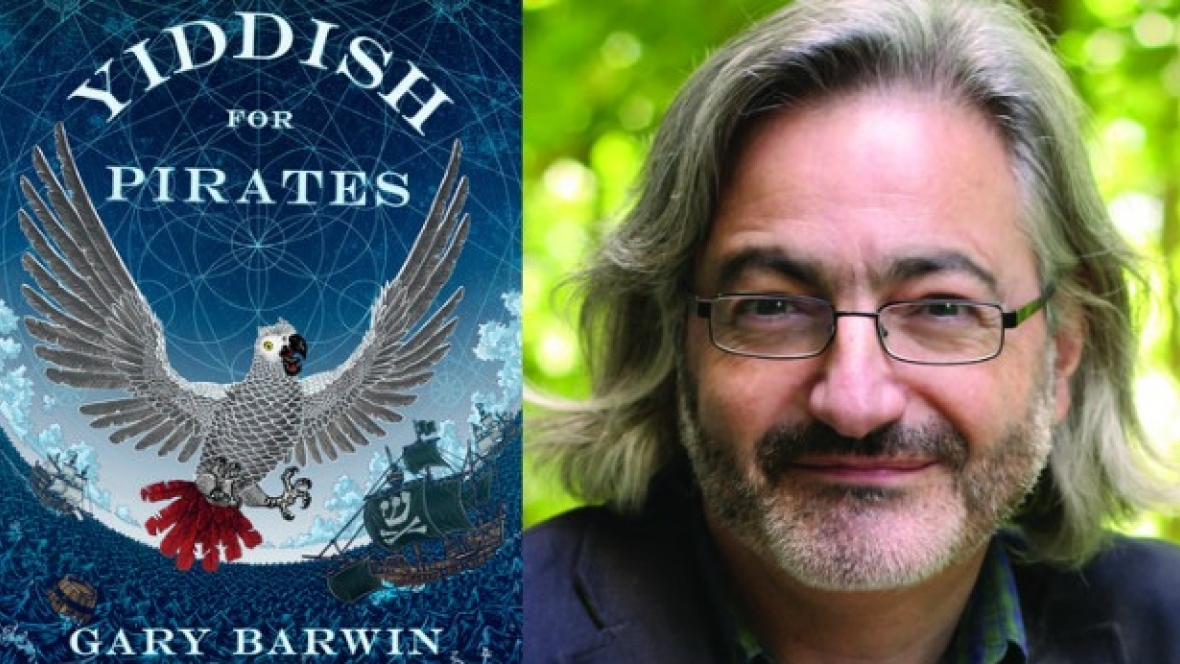

“Considering the Book as Bi(bli)osphere,” an Interview with Gary Barwin

By James Lindsay

The writing of poet, composer, and recently Giller nominated novelist Gary Barwin has music to it that sounds like a gathering of organic materials, processed and released over and over until they sound alien. His style is both a preservation and modernization of surrealism, one that emphasizes tune and humor. The source material is familiar, but the affect of interacting with language reordering itself can be otherworldly, forcing the reader to reconsider what they thought recognizable. Perhaps his rhythms can best be understood in contrast to the conceptual work composers like Steve Reich, John Cage, or Barwin himself: traditional in that they look back for inspiration, but progressive because they are compelled to present established ideas in brave new ways.

James Lindsay:

In your new collection, No TV for Woodpeckers, a line in the notes for the poem "NEEDLEMINER" struck me: "Language isn't a virus from outer space. It is our environment." I found this fascinating because for me so much of your work is about presenting language in new, challenging, almost alien ways. Could you elaborate on this thought?

Gary Barwin:

It’s always great when the most memorable line comes from the notes and not the poems! But it is an excellent question, key for that section of the book. I do think that we often become inured to language. We stop noticing it, how it works and how it frames our way of experiencing and thinking about the world and ourselves. Like that David Foster Wallace line about not asking a fish to comment about water because they don’t notice it since it is their environment. As ad-iconic Madge says, “You’re soaking in it!” Through writing, we can “make strange” our language, our perceptions and our way of thinking and so we can both know what we are thinking without knowing it, as well as being able to imagine other ways of imagining.

Rimbaud says, “I is another,” and for me, language is both other and us. Lately, I’ve been thinking of it like the microflora that live our in our gut. It’s symbiotic.

In the line that you quote, I also meant the term “environment” literally. The poems in that section repopulate other poems with the names and terminology of life forms (plants, animals, insects, etc.), which can be found where I live—Hamilton, Ontario. Like the symbiosis we experience with both microflora and language, we live in symbiosis with the environment around us. As some of the remarkable recent poetic work of Adam Dickinson shows, it writes us just as we write it. So maybe, I should have said: “Language is avarice that comes from author space. And vice versa.”

JL:

I love this idea of poems "repopulating" other poems. What do you think authorship looks like when the poems begin to have symbiotic relationships with each other? Does the poets become more park ranger than creator?

GB:

Hmm. Makes me think: Was I originally populated with language? Are there waves of language migrating to me? Or does “me” as the author migrate to the language, the poem?

I think this process of “repopulation” is just replicating what is a natural process, though less explicit, that occurs in most literature. In the “repopulation” poems in the book, I am not only exploring the process of how poems are made but also the literal ecological situation in Hamilton. How there exists a vastly greater diversity of life in the city that one might expect, and, further, that there has been a concerted effort to reestablish indigenous species there. The city isn't all roving bands of spent Roll-Up-the-Rim Tim Hortons cups.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

But I do love your idea of poet as park ranger, though I’m tempted to consider the reader as being the one in the role of park ranger, observing, considering the relationship between the writer and the language, between the language in general and the specific text before them, considering the book as bi(bli)osphere.

It’s true you probably can’t read one poem without considering it in relationship to others, just as it might be hard to conceive of the self as independent of others relative to it in time or space. Propinquitous.

I do think all language and all thought occurs in relation to others. We always exist in an ecosystem, both conceptual and physical. Though the conceptual and the physical are necessarily themselves interconnected in us. In actually writing the poems, I did find exploring the structures and the forms of the source poems a very productive and inspiring process.

JL:

Speaking of repopulating, why are so many poems in No TV for Woodpeckers second section, "Marlinspike Chanty," dedicated to other poets?

GB:

It’s a thinly veiled and desperate attempt to get them to like me—y’know, like most of my work…but truly, as we were talking about up there (é) I feel that writing occurs in the context of other writing and, often, community. But always from dialogue. I think of myself as writing from shared and interconnecting concerns shared with others, whether writers or not. Many of the pieces in the book actually came from discussions with the dedicatees—in IRL or on social media. Some of them originated from discussions, a poem which I read, a shared line or quip, a recommendation or a link to something—writing, trivia, images, articles, etc.—or from collaborative projects. The resultant work was often influenced in both form and content by the person that it was in dialogue with.

JL:

You have worked collaboratively with other poets in the past (Stuart Ross, derek beaulieu, and Gregory Betts to name a few). Yet writing is often a solitary process, so how does working with a dialogue, whether in direct collaboration or writing in the context of other writing and community, differ from writing by yourself?

GB:

I’m not sure that I ever really write by myself, since, as I said, I feel that I’m always writing in the context of other writing and community, however, writing in direct collaboration with other writers is definitely different. For me, it’s like the difference between hitting a tennis ball against a wall and playing with an actual person. There are surprises in both cases, but obviously, another player sends you unexpected shots, shots that are specific to the way you play and the relationship between the two of you, and the particular context. So, when Venus Williams and I play, like that last time at Wimbledon, I often change my pawn for a queen after the face-off in the third down.

I love the rallying, the sparring, the surprises, the mock competition of collaboration. But also the planning together. I guess it’s like paddling a canoe with a partner. Actually, last month, Gregory Betts and I went out for a long literal littoral literary canoe on the Jordan River and discussed a new plan our ever-evolving long poem in progress. We ended up in a very different place than I expected. And surrounded by geese.

Writing by myself involves me not thinking about someone else or myself so much, but instead trying to be attuned to what is happening on the page before me. It involves being open to the text and what it suggests, and trying to be aware of where the writing seems to want to go, or where it could possibly go, and what it might become. Being receptive, taking chances, not having fixed ideas. But writing by myself also requires me to be sensitive to what is going in my mind. What the text feels like reflected in there. What are its rhythms, resonances, associations, both as they seem to appear on the page before me but as it rebounds about my brain and body.

JL:

We have discussed the relationship between you and collaborators when it comes to writing, but what about reading? How do you view the relationship between you and your readers? What do you think of reading when you are reading? Is it still symbiotic or more parasitic in its one-sidedness?

GB:

My relationship with my readers? I imagine my readers impatiently waiting for the time when they can lift me onto their shoulders and carry me with much celebration through the streets of the city, all the while singing lines from my work and bedecking me with the iridescent dazzle of their comfort with negative capability.

But ideally, readers would be involved in a kind of linguistic tango with a text. Sometimes the text would lead, but sometimes the reader would send it signals to see how it might respond. They’d be an antennae, ready to pick the slightest tremor or signal. But the text could be, too. Like a tango dancer, ready to turn on a dime. It’d be a give and take, signals sent back and forth between reader and text, sounding each other out, echolocating each other, figuring out the nature of what they each are.

But one very practical thought that I have about readers: Because I write in several different ways and forms (from “experimental” poetry and fiction to more conventional fiction and even children’s writing) I often think about the particular reader who might encounter the work. The expectations and approach to reading that they might bring to the text. (Hey, that’s a pretty terrible window you have there. Yeah, that’s because it’s a glass of water.)

In terms of my reading, I love Charles Bernstein’s notion of “wreading,” which is some combination between reading and writing based on creative interactions with a text (see “Wreading, Writing, Wresponding” in his Attack of the Difficult Poems.) Its true that when I read a text, as a writer, there is always an element of potential creative response. I engage the world through writing so it’s natural that I might engage a text through writing. It’s a kind of triangulation: reading and writing forming two points of the three.

But I’d also say that reading teaches me about reading in general as well as about my own reading specifically. Reading reads reading, I think. What is it to read? How do we read? How can we read? What do we read when we are reading? What are the forces engaging and pulling us as we read? Capitalism, sleepiness, narrative, grammar, envy, Wernicke’s area, patriarchy, our cellphones, hunger, reality cosplay, and the blatherating tickertape of thought.

But really, since books are becoming more and more interactive, what with retina scanning and all, it won’t be how we read but how our books read us. I worry about the rating I’ll get from those books on Goodreaders. Barwin drifted off between page 7 and page 11. He missed the allusion to John Donne on page 23. Also, he wept mawkishly when the little dog saved the child.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

James Lindsay has been a bookseller for more than a decade. He is also co-owner of Pleasence Records in Toronto, a record label specializing in post-punk, odd-pop and avant-garde sound pieces.