Home

By Nancy Jo Cullen

This October I travelled to Calgary from my home in Kingston to do some book promotion and to catch up with my family and cherished friends. It had been a little over a year since I’d returned home, which I suppose, is a funny way to think of Calgary since I haven’t lived there for over a decade. Ask my kids where they’re from and they will tell you, they’re from Toronto; ask me where I’m from and I’ll say I’m from Kingston with the caveat that I’m actually from Calgary, although I was born and raised in B.C. And though I am now resolutely from southern Ontario, as my partner and children are all firmly rooted in this place, I can’t help but tell people out here that I am actually from Calgary.

That being said, it was being away from Calgary that allowed me to write about the city that shaped me, a place I still love. But I needed to leave Calgary, I needed to forgive Calgary for hot mess I’d gotten myself into there, and I needed to leave behind the “lake of fire” anti-queer rhetoric that sometimes bombasts across Alberta’s media. Still, it’s important to note that Calgary is also the city I where I became a feminist activist, it’s the place where I first connected with the left-wing ideas that helped me to start thinking more critically about income disparity and to start unpacking racism (lifelong process alert!), and it’s the place where I came out into a small but robust queer community.

When my kids and I left Calgary I had a pretty good idea that we wouldn’t be returning. However I kept that to myself, technically we were going to live away from Calgary for two, maybe three years. There was no way of knowing if our move to Toronto would be a disaster even if I looked forward to introducing my kids to the rich diversity of the city. But as I hoped, despite the distance from family and friends, my kids and I thrived in Toronto. Although one outcome of the move I hadn’t anticipated was the longing I would have for Calgary. I didn’t regret our move to Toronto but I missed Calgary’s crisp, blue winter skies, and I missed my people: my family, and my brilliant and resilient friends.

Calgary has a reputation as a redneck city, much of it deserved. But I know an alternative Calgary and my distance from the place made me want to write about the Calgary I know. I wanted to describe a more nuanced city to people who don’t know Calgary. I began work on my novel thinking I would write a sweeping social drama about politics and history (which, in retrospect, is funny because I almost always prefer a tight, short novel), and I ended up with a small book about a family living in Calgary during a particularly turbulent era. I began with the idea I would write a novel about place and ended up with a novel about home.

After you finish writing a novel—if you are lucky—you will be asked to talk about your book, like you know how and why you did things. In my case, so much of my novel happened because what I began with simply didn’t work. But, since I’ve been fortunate enough to talk in hindsight about my novel, I have been thinking about why place as home is important to me as a writer. What do I want to try to understand about belonging, to a family, to a group, to a city, or to a country? And how do I tell those stories in a way that is true to the history of a place, whether it is difficult or not?

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

Of course, these are questions that can only be explored, not emphatically answered. I know that I want to talk about place and home in a way that troubles simplistic answers and heteronormative tropes. I want to rattle the bones of the idea of happily ever after, of “deserving” and “undeserving.” And yes, I want to dismantle our capitalist patriarchy but, as that work carries on, I’ll settle for a good story or poem that pushes back against traditional narratives of family and home making. Maybe feeling at home in two places, and also at home in neither, is the situation I required to best explore these concerns in my writing. Maybe, for me, shallow roots are preferable to deeper ones.

Funnily enough, when I was in Calgary for those first two weeks of October, with skin and hair parched by the arid climate and “enjoying” two snowfalls before Thanksgiving, not to mention suffering from a wee bit of jet lag and missing my partner, I thought: it will be good to fly back home. It should come as no surprise then, that on my last trip home to Calgary, I found myself telling people that while my parents were both raised in Calgary, and that while I had spent twenty-three years living in in the city, I am actually from Kingston now.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

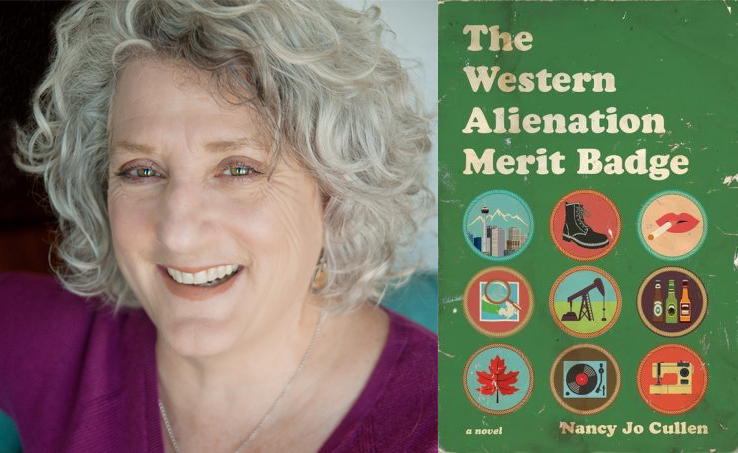

Nancy Jo Cullen is the fourth recipient of the Writers’ Trust Dayne Ogilvie Prize for LGBT Emerging Writers. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Guelph and her short story collection, Canary, was the winner of the 2012 Metcalf-Rooke Award. Her poetry has been shortlisted for the Gerald Lampert Award, the Writers’ Guild of Alberta’s Stephan G. Stephansson Award and the City of Calgary W.O. Mitchell Book Prize. She lived in Calgary for over two decades and still returns regularly to connect with family and friends. She now lives in Kingston, Canada.

Nancy's latest novel, The Western Alienation Merit Badge, was published in Spring 2019 by Wolsak & Wynn, to wide critical acclaim.