On Synchronicity and Writing: The Path Back to Myself

By Shazia Hafiz Ramji

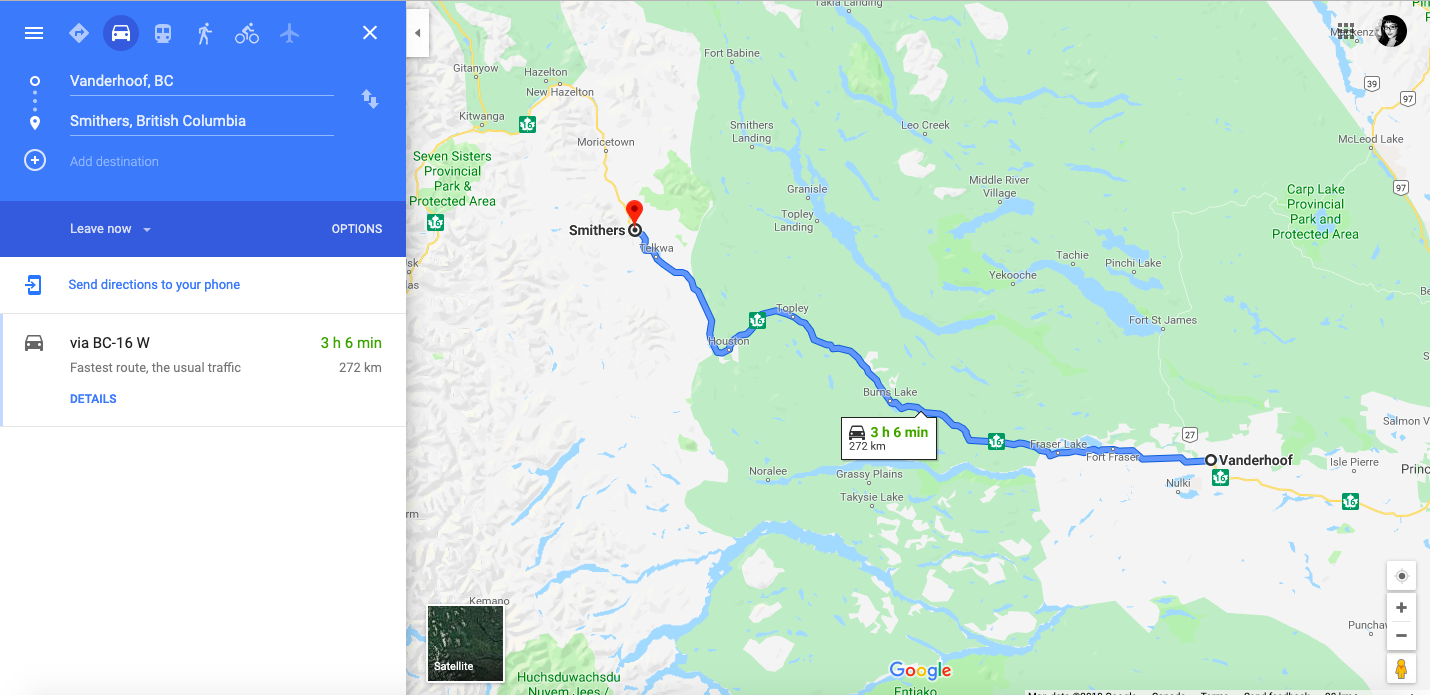

Last month, I had the privilege of going on a road trip across Northern BC as part of an author’s tour organized by the BC and Yukon Book Prizes, for which my book of poems, Port of Being, was a finalist. I had only ever been to the north once before in 2017, when I flew into Prince George. The the BCYBP tour also began with a flight into Prince George, but over the next few days, we drove to many towns like Vanderhoof, stopping along the way at Fraser Lake, Burns Lake, Smithers, and Hazelton before the last stop in Terrace. I was on the road with Tim Carlson, tour driver, guide, and Theatre Conspiracy artistic producer, and Lianne Oelke, fellow finalist and Super Smash Bros. pro. We amped each other up every morning with coffee and snacks before visiting schools and libraries, where we met young, energetic dreamers and made poems with them. We made jokes and looked for road signs announcing the CBC Radio frequencies. We ate wine and drank pizza. We saw a lot of trees. A lot of trees.

I’ve seen trees before, of course, but I felt like I saw trees for the first time in a long time on this trip; I looked at them – I actually saw the trees: I began to think of the names we’ve given them, the way they move, the way the light moves through them, their gathering and speech, their colour I can only describe as green because language is inadequate for their beauty.

Yes, I had a tree moment. Have you ever seen birch trees?

We were flanked by birch trees throughout the three-hour drive from Fraser Lake to Smithers. In the comfortable silence and the light and green slipping past, I eased into my happiest self, noticing the ribbons of light cutting across pale birch trunks, light that reminded me of sun on water, or of a sonorous high-pitched singing, which I felt in my throat, and which I heard when I looked at the birch trees. I used to feel this way all the time when I was a kid. One of my happiest memories is of sticking my feet out the window of the car on the long, dusty road into the country, where my aunt lived, far away from us in the city. In that other country, I would look at the rock faces, the trees, the zebra, and I would feel so happy that they had lived before me and with me, and I wished that they would live forever: beyond me, beyond my family, so that this beauty would last forever. I would force myself to keep the awe in my throat, in case anyone saw me crying and thought something terrible had happened. When we got to my aunt’s house, I would run upstairs as fast as I could, away from all the adults, where that awe became a tic: I would write little descriptions, one after the other, like a list, as if writing all of it down would keep that beauty. Later, when a kind teacher saw what I was doing in class, she told me it was poetry.

Driving past the birch trees on the way to Smithers, I had overpowering feelings and thoughts like I used to when I was little. The trees were so beautiful that I wished with all my heart to plant a tree! I wished so much that I could plant a tree. I became self-aware after having that thought: I had never been the kind of person who would go out of her way to plant trees. Thinking of my life as it is now, I would likely never be able to go tree planting. I became sad after this thought. Imagine how many lives you could live, if you only had time and were elsewhere. I wanted to plant a tree at that moment because it felt like the most beautiful thing anyone could do. It probably is. After my overpowering childlike wish to plant a tree, I thought about my life now and felt immensely grateful for my family, friends, teachers, and books, and I felt especially grateful for my students, who remind me constantly of the beauty all around us. I snapped back to adult life and suggested we stop for a snack at a café at Burns Lake.

At the Boer Mountain Coffee House in Burns Lake, I was picking up cheese puffs and chocolate macaroons (my eating habits are still in the kid phase) for the road, and when I turned to pay, I bumped into my student – my poetry student from Vancouver. When she called me, I forgot we weren’t in Vancouver. It took me a minute to understand where we were. We were both so surprised to bump into each other in Burns Lake. “What are you doing here?” we said. I told her I was on tour with my book, talking poetry and writing poetry with students. She told me she had come here to plant trees.

Later that night, I sat over the desk in my hotel room in Smithers, trying to articulate the synchronicity of the tree moment. I couldn’t. Instead, I wept. This is what a moment of faith looks like, I remember thinking, facing the wall across me. This is what it means for me to give meaning to that moment of faith:

1) I understand that things just are. It just is.

2) I’m in it (i.e. I’m alive, I’m here, now, in the “it just is”).

3) I notice it (i.e. the birch trees; my wish to plant a tree).

4) I choose to follow that pattern of noticing (i.e. the birch trees; my student who was planting trees; the synchronicity).

This is how I became a writer.

Then there’s the fifth one:

5) I choose to trust it.

Sometimes this trust feels electric and vital. It leads me back to my writing, to the small shifts of perception where it happens. It leads me back to those tender, imaginative wishes of childhood that were filled with an awareness of death. It leads me back to myself.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Shazia Hafiz Ramji’s fiction was shortlisted for the Malahat Review’s 2022 Open Season Awards. Her poetry was shortlisted for the 2021 National Magazine Awards and the 2021 Mitchell Prize for Faith and Poetry. Shazia’s award-winning first book is Port of Being. She lives in Vancouver and Calgary, where she is at work on a novel.