So You Want to Write About Race

By Jen Sookfong Lee

Somehow I have become on expert on writing race.

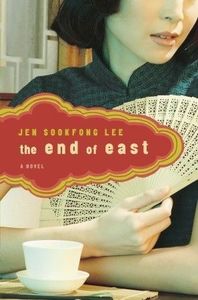

This was not something I planned for. When I started publishing, I was writing fiction about Chinese Canadian characters, about families who had been invisible in Canlit, not because of politics really, but because it was a story I knew I could write that also hadn’t been told yet. I was 23 years old (the same age as Justin Bieber!) when I started The End of East and my politics were ill-formed and probably pretty stupid. When the novel was published, I was unprepared for how much people wanted me to talk about race, about other Asian authors, about immigration, about diversity in publishing, even about the effects of Chinese investment on Canadian real estate prices (not a topic I enjoy, so please stop asking me). After a few months of promoting The End of East, I developed stock answers that were designed to both deflect attention from my race and to make people laugh. My favourite? Whenever someone at an event asked what the Chinese Canadian community thought of my book, I would answer, “There are 1.5 million of us and I haven’t had time to talk to everyone. But I’m pretty sure at least half a dozen think it sucks.”

Ten years and five books later, I have come to an uneasy peace about my position as The Accessible Inclusion Lady of Canlit, influenced, at least partly, by the number of young writers of colour who write or talk to me at events, asking if they will get published, if there is a place for them in our industry. My visibility, I’ve come to learn, is important for them. My willingness to speak about representation matters to them. For this reason, the space I’ve been given to speak about race and appropriation and diversity is one that I’m happy to occupy, even if I sometimes don’t want to, even if I would rather be asked about my craft or research or how much I will always love Possession by A.S. Byatt.

(And I should say that not everyone who is asked to represent a community needs to or should. Some prefer to let their literary work speak for their politics. Others would rather leave all of that alone. That’s all good!)

But what do I say when someone asks, “But Jen, how do I write about race when it’s not my race?”

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

This is a question I’ve been asked hundreds of times, usually by emerging writers, but also sometimes by established ones who are now wrestling with the idea that writing race requires some measure of accountability. I take this topic very seriously, although I admit that I’m sometimes tempted to respond with, “Would you ever ask Dave Eggers this question?”

- Question your idea. Before you get started, ask yourself, “Am I the person to write this story?” So often, problems arise when writers try to tell stories that are strongly and identifiably tied to specific communities. Are you the person who should be writing a story about residential schools, or internment, or refugee camps? Can you tell this story with more or less authority than someone from that community?

- Give your characters space. A diverse cast of characters is great! It’s ideal! But take care to identify your characters with other markers, not just race. Every character, no matter how secondary, deserves enough space to be the hero in their own stories, even if those stories are only one paragraph long. Hint at their backstories. Tell us how they’re acting and what they’re wearing. Make sure we know them as something other than That [insert race here] Person.

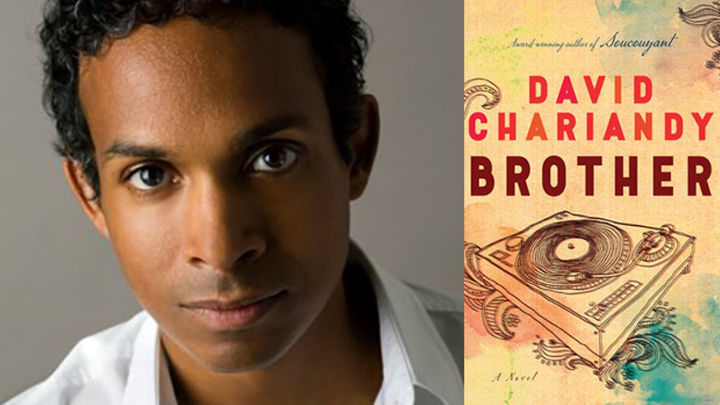

- Refer to race without stating race. When I finished reading Brother by David Chariandy, what struck me was that his characters were young men from all kinds of families, but he did not identify their race to us. Instead, he described what kinds of haircuts they had, or what they cooked, or gave them names from a specific language. In this way, we knew what their race was, but these markers gave us more than race, they gave us genuinely interesting details that helped us get to know these characters better than just race ever could.

- Approach your characters as you would a human in real life. Whenever we meet people at a party or in line at Starbucks, we start conversations with generosity and understand that we begin not knowing anything about them, and that the process of familiarity is full of surprises we can never anticipate. This is the same for your fictional characters too. Real humans will never conform to a stereotype or a fetish and our characters shouldn’t either. How will they surprise you? What will you discover about them that is delightful or disturbing or challenging?

- Do the work. It really comes down to research, finding the right sensitivity readers, and constantly questioning your narrative decisions. Writing a book is always an exercise in hard work, in doing more than you thought you could. Race, like dialogue or setting or plot, requires time, revision, and a critical eye.

As you embark on your writing project with this list in mind, I want you to ask yourself one more question: can you make space for writers from marginalized communities to tell their own stories? Buy a book from an emerging writer of colour. Attend a reading featuring someone whose work is new to you. After all, accountability doesn’t stop when you’ve written what you want. Accountability extends to creating opportunities for everyone. Life, like the best fiction, is expansive, diverse, and cacophonous. Embrace that. It’s a beautiful thing. I’m The Accessible Inclusion Lady of Canlit. You can trust me.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Jen Sookfong Lee was born and raised in Vancouver’s East Side, and she now lives with her son in North Burnaby. Her books include The Conjoined, nominated for International Dublin Literary Award and a finalist for the Ethel Wilson Fiction Prize, The Better Mother, a finalist for the City of Vancouver Book Award, The End of East, The Shadow List, and Finding Home. Jen acquires and edits for ECW Press and co-hosts the literary podcast, Can’t Lit.