Soundwalking Through the Pandemic

By Shazia Hafiz Ramji

Every year, there are a few times I think I’m free from the grip of depression. And every year, there are a few times I realize that I’m not. Years ago when I was diagnosed with major depressive disorder, I had to learn to stop becoming self-destructive. Now when the depression returns, I think: shit, I have to go outside and listen.

Would it be strange to say that listening continues to save me? I didn’t know that it did until I wrote Port of Being. I was unemployed at the time, which gave me the chance to wake up at 6:30 a.m. and walk the city regularly – all the way from my home in East Vancouver to the harbour (close to two hours at a leisurely pace). I collected sounds on those walks through field recordings and notebooks: bits of overheard conversation, inventories of noise and silence, machinic textures of the city.

I had also been stalked and diagnosed with PTSD. Listening was a way of learning to live again – “to bring myself into relation again” – and here I quote myself from the author’s note at the back of my book, because I did actually turn to it this November to remember what to do when my depression peaked.

And so, a couple of weeks ago, I went on a soundwalk. It’s a little more than a walk without your phone and your headphones. Soundwalking, according to composer Hildegard Westerkamp, is “any excursion whose main purpose is listening to the environment. It is exposing our ears to every sound around us no matter where we are.”

“Soundwalking” as a term first emerged in Vancouver in the 1970s as part of the World Soundscape Project, founded by R. Murray Schafer, a Vancouverite, composer, and author of many books on sound, including The Soundscape and A Sound Education: Exercises in Listening and Sound-Making, which I’ve been using to stave off pandemic depression.

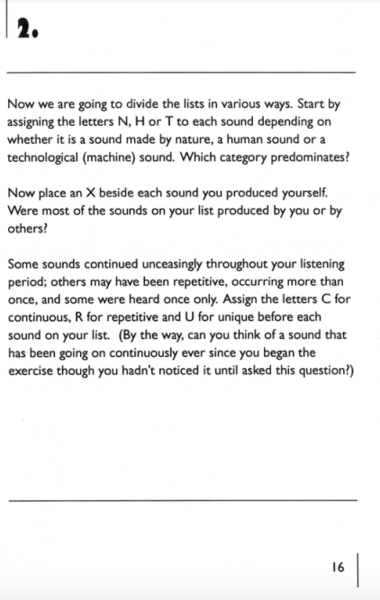

The first exercise asks you to list all the sounds you can hear. My favourite is the second one, which asks you to categorize them:

While categorizing sounds on my soundwalks, I’ve noticed that the ones labelled “C” (continuous) and “U” (unique) increase with every soundwalk. This means that I’m allowing myself to hear things I had not heard before.

In The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World, Schafer quotes Marshall McLuhan on the totality of terror and Schafer says that ”the ear’s only protection [from terror] is an elaborate psychological mechanism for filtering out undesirable sound in order to concentrate on what is desirable. The eye points outward; the ear draws inward.”

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

It may seem odd to think that soundwalking is a way of managing terror – in this case, I’m choosing what to listen to and what to allow – I’m refusing the noise of the pandemic, which makes my depression worse.

Isn’t that just mindfulness, though? Listening is a part of mindfulness for sure, and soundwalking can be too, but soundwalking is more than mindfulness. Soundwalking is an exchange between ourselves and our environments. It demands a recalibration of the senses by asking us to listen actively – to do nothing but listen. For Schafer, the ear is an “erotic orifice.”

In “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power,” Audre Lorde reclaims the “erotic” from its mainstream associations with sexualization to remind us that it is “creative energy empowered.” It is about the depth of experience, “an internal sense of satisfaction,” and that once we’ve experienced “the fullness of this depth of feeling,” we can expect no less of ourselves.

Soundwalking is an erotic experience that has allowed me to reclaim a depth of feeling when depression and pandemic-terror constantly strive to numb and reduce it. It’s no surprise then that listening has taught me how to live, again and again, this time through soundwalking.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Shazia Hafiz Ramji’s fiction was shortlisted for the Malahat Review’s 2022 Open Season Awards. Her poetry was shortlisted for the 2021 National Magazine Awards and the 2021 Mitchell Prize for Faith and Poetry. Shazia’s award-winning first book is Port of Being. She lives in Vancouver and Calgary, where she is at work on a novel.