THREAD! The Role of the Twitter Essay in CanLit

By A.H. Reaume

When most people think of Twitter, they think of the short and pithy 280-character messages that the platform is best known for. But perhaps the most interesting content on the social network is shared via Twitter threads--strings of tweets that talk about an issue in greater depth. If you’re on Twitter and you follow Canadian or Indigenous authors, you know a good Twitter essay is making the rounds when everyone in your timeline is retweeting it.

This mass sharing of Twitter threads and the responses that these threads generate has created communal conversations across CanLit—often between authors who wouldn’t ordinarily be in conversation because of differences in geography, genre, positionality, or relative CanLit power and prestige. In that way, Twitter threads are reshaping CanLit in small but important ways by forging new connections and elevating voices that have been traditionally excluded from conversations about CanLit that have previously taken place almost exclusively in traditional media outlets or in academic spaces.

So, what is the history of the Twitter essay in CanLit and why do so many write and share them? And, perhaps more importantly, how significant have these threaded tweets been at resisting some of the discriminatory or exclusionary practices in CanLit and sparking important conversations about the literary community and its practices?

The History of the Twitter Essay

It might surprise you that the Twitter essay as a genre has its roots firmly planted in Canadian literature. Noted Twitter essayist Jeet Heer, a Canadian author, literary critic, and a staff writer at The New Republic, was one of the first people to thread tweets and helped define and popularize the genre.

While Heer credits David Frum, the political commentator and senior editor of The Atlantic, as among the first to start numbering his tweets to create essays, he acknowledges that he played an important role in spreading the form--which Twitter later helped legitimize by introducing the capability to ‘thread’ tweets in late 2017.

Heer’s first forays into Twitter essays were an attempt to parse why Rob Ford was so popular despite his frequent racist and homophobic comments. By thinking through this issue via Twitter threads and listening to the feedback of his followers, Heer was able to understand Ford and his supporters better.

“I now saw Ford less as a freak show than as a symptom of much deeper problems in Toronto and Canada,” he said in a 2016 article in The New Republic titled In Defense of the Twitter Essay. This realization informed articles he later wrote in Toronto Life and the New Republic.

Heer was hooked on the form and began tweeting out so many Twitter essays (which at the time were often referred to as tweetstorms), he was called out as a ‘manthreader’ by Gizmodo in 2016.

The Gizmodo article was partly in response to Heer’s infamous thread about why so many people have sex with animals and vegetables in Canadian fiction, which Heer wrote when Nick Mount resigned from The Walrus after he published a short story by Stephen Marche that featured a man having sex with an owl.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

That thread, which tacked how settler colonialism, race anxiety, and national identity influence Canadian literature’s preoccupation with those themes, is an excellent example of how Twitter essays foster important conversations about books and literary culture in Canada which might be hard to find a home for in the mainstream press or even literary publications.

Why Twitter Essays?

One thing about Twitter that struck Heer when he first signed up for the platform was its diverse voices.

“It included a much higher percentage of women and people of color than can be found in Canadian media,” he said.

That means that people who might not have access to another platform can use Twitter as a way to speak out on an issue. That broadens the kinds of topics that can be discussed by the CanLit community since there are no gatekeepers deciding what’s important and worthy of publication and what isn’t.

Like Heer, many prominent threaders in CanLit also use Twitter as a way to talk through issues that they later publish longer pieces on. Writer Gwen Benaway is well-known for her incisive Twitter essays in which she tackles things like sexual assault and harassment and transphobia. Those that follow Benaway’s work and Twitter feed closely will note that she often writes creative non-fiction essays or articles that delve deeper into the issues she tweets about.

For example, Benaway originally talked about the transphobia she experienced during multiple ER visits in a Twitter essay before she wrote a compelling article about it for The Globe and Mail.

But not everyone wants or has the time to write an article based off their Twitter essays. In fact, when writer Erika Thorkelson decided to focus her energy on finishing her novel this summer instead of writing articles, she realized that her thoughts would still need an outlet. “I’ve committed my summer to finishing this novel I’ve been working on forever, so Twitter will be the place where I shunt all my essay writing urges. Sorry guys. There will probably be a lot of threads,” she tweeted.

As a disabled writer, I began writing Twitter essays when I was in a middle stage of recovering from a brain injury that limited the time that I could spend on computers and other devices. I wanted to speak out on issues that were confronting CanLit and also on my experiences as a person with a disability, but couldn’t manage the screen time needed to write full-fledged articles, research outlets that might be interested in publishing them, or set up my own blog.

Twitter essays were a more accessible form to share my thoughts and I found a community that didn’t just comment on or ‘like’ my essays, but shared them. Sometimes I wrote threads while I was incapacitated from fatigue and unable to leave my house and it helped me feel less alone to see how my voice could still be part of a larger conversation.

The Many Uses of Twitter Essays in CanLit

Twitter essays have become a way for many marginalized or emerging writers to start important discussions about the abuses and exclusions in CanLit. In fact, Twitter essays have been a key way to push back at how CanLit operates and to call for a better CanLit. This type of resistance to the CanLit status quo is unprecedented. For the first time, more voices are insisting on being heard and rather than being silenced Twitter is offering a platform to help connect those voices with other writers who are listening.

In contrast, gatekeepers from traditional media platforms give prominent writers like Margaret Atwood coverage and access to write editorials, but often don’t seek out or publish other voices in response. On Twitter, whose voice gets heard isn’t based on how many books you’ve sold. If you write something interesting and relevant in a Twitter essay, it could get shared widely across CanLit Twitter, even if you’re an emerging writer who no one has heard about. In an era of CanLit that has often been linked to a dumpster fire, this has provided a space for responses and rebuttals to some of CanLit’s recent fires from people who aren’t as entrenched in the industry.

In fact, many great CanLit Twitter essays specifically parse articles written in the mainstream press about CanLit controversies as a way to provide an alternative narrative and perspective. The fact that these essays are published on Twitter, instead of in traditional media, means that the response is swift. While sometimes these issues are later also covered in literary magazines or more mainstream outlets from similar perspectives, the immediacy of Twitter means that tweets fill a vacuum until there is time to formulate a more polished response.

Some of the most salient Twitter essays have come in response to UBC Accountable. For example, take Sierra Skye Gemma’s 74 tweet letter to Margaret Atwood. It was published on November 17, 2016 right after the UBC Accountable letter was released and Atwood wrote an article in The Walrus in which she warned those questioning UBC Accountable, “should give some thought to the consequences.” In her Twitter essay, Gemma talks about why she supported the M.C.’s complaint against Galloway and points out how power in CanLit operates and limits her own reach to Twitter.

“I realized if I went forwards as a witness, my life would change forever…. The #canlit establishment would hate me. They would call me a liar. My name would get dragged through the mud… I’d never be published again. Which is… why my letter is a series of tweets and not in @walrusmagazine,” she tweeted.

When it came to pushing back against power in CanLit in regards to UBC Accountable, writers like Alicia Elliot, Gwen Benaway, Lucia Lorenzi, Chelsea Rooney, and many others have been particularly eloquent on the subject, while some of the letter’s most vocal proponents, Margaret Atwood and Susan Swan, have posted on Twitter about the issue, but have also often bypassed the platform entirely and gone to the mainstream media.

Interestingly, despite the fact that Atwood has almost 2 million followers, her posts on UBC Accountable tend to get far fewer retweets and likes than those of the writers who challenge her on the issue—showing one way power functions differently on Twitter than in other parts of the CanLit community.

Twitter essays became a way for people who didn’t support UBC Accountable to better articulate that the UBC Accountable letter was dangerous because it might silence victims of other abusers in CanLit. But they also served to show women who had yet to come forward about those other alleged abusers that there was a community of writers who were willing to support them. This support was later concretized through a fund launched by Alicia Elliott to support women writers in case they are sued for libel after coming forward with accusations of assault or harassment.

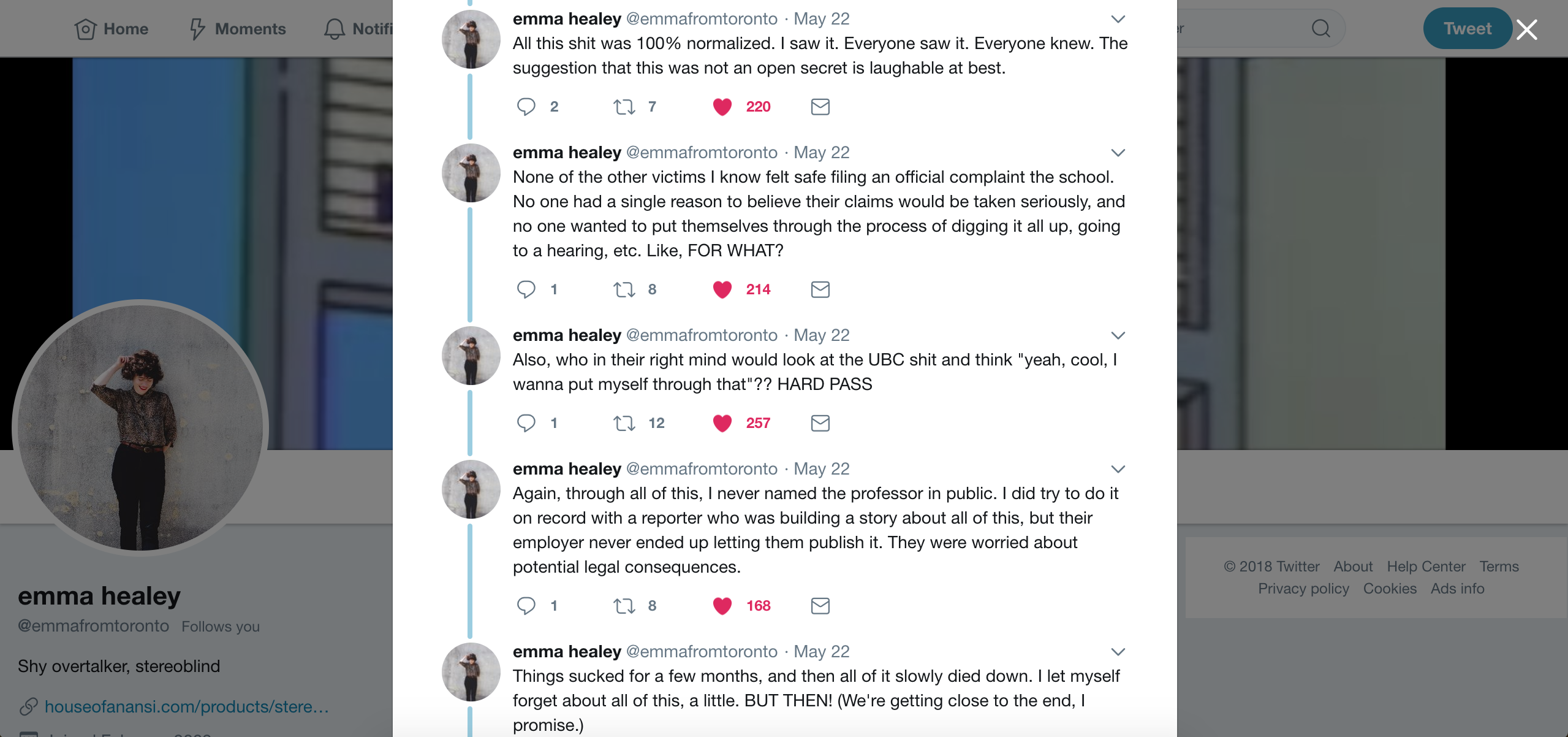

Similarly, Twitter has played a key role in the controversy surrounding the Concordia writing program. While Emma Healey published the article Stories like Passwords, which detailed her experience in the program, in The Hairpin, she decided to reveal who was the subject of the allegations in that piece in an eloquent Twitter thread that many (including this writer) watched being written tweet by tweet in real time. Healey used her Twitter essay as a way to call for other victims to come forward if they were able to. Healey might also have chosen Twitter because mainstream publications would have been too concerned about libel suits to publish her essay.

While writers like Daniel Heath Justice, Chelsea Vowel, and CanLit scholar Lucia Lorenzi responded to the Boyden and Appropriation Prize controversies with Twitter essays, perhaps the most poignant Twitter thread about the issue was from Elliott, who eloquently expressed her dismay at receiving her copy of Write Magazine in which she had published an essay about appropriation, and seeing the editor’s note by Hal Niedzviecki proposing the Appropriation Prize. In her thread, Elliott says, “This is why I'm increasingly feeling like I don't have a place in CanLit as a Tuscarora woman.”

While there were many writers like Kateri Akiwenzie-Damm and Joshua Whitehead who wrote articles about the issue of appropriation in the aftermath, Twitter essays played a huge role in spreading news about what Niedzviecki wrote, swiftly speaking back, and also fundraising for the Indigenous Voices Awards.

That wasn’t the last time Twitter essays helped fund a new literary prize. Vancouver-based writer Yilin Wang also used Twitter threads to talk about her experience after overhearing racist comments about Chinese writers at a local literary event. That led her to start the #racismincanlit hashtag. That hashtag caught the eye of Toronto-based fundraiser Rahim Ladha who was inspired to start three awards for marginalized writers: one for BIPOC or trans or Queer writers named Spark, one for disabled writers named Echo, and one for queer women, femmes, trans, and non-binary writers and illustrators writing science fiction and fantasy in North America named Nova.

Twitter threads also played a significant role in changing the programming at GritLit this year after they put forward a panel that was named after Alicia Elliott’s article CanLit is a Raging Dumpster Fire, but that featured two white writers, Nick Mount and Elaine Dewar, talking about issues like UBC Accountable, and the appropriation prize and Boyden controversies. When Elliott questioned via a Twitter essay why she wasn’t invited to a panel whose title and description cited her and which heavily borrowed from her intellectual work, a new panel moderated by Jael Richardson with Alicia Elliott and Carrianne Leung was organized.

For those who weren’t able to attend, writer and The Fold Festival’s communications and development coordinator Amanda Leduc live tweeted using The Fold’s twitter account. Writers and readers from across CanLit were able to follow along on the thread as the panelists talked about the continued problems with CanLit and resisted the impulse of many more privileged writers to be hopeful that things will quickly change in the industry.

"Hope is a tricky thing,” said Richardson. “For me personally, there has to be hope to keep me going. But the danger is that people expect you to move into hope quicker than you're ready. People who aren't fighting want to be more hopeful because they don't want to get involved--they don't want to get in the trenches themselves.”

After the panel, Elliot, Leung, and Richardson used Twitter essays to talk about the experience of doing the panel and having to deal with the white fragility of audience members who highjacked the question period.

Twitter essays have also been used to confront ableism in literary communities. For example, writer Jael Richardson used a Twitter essay to announced a petition to get the local library branch she uses and which previously hosted The Fold events to make their washrooms accessible.

All these Twitter essays addressed important issues affecting writers from groups who have often been excluded, marginalized, or discriminated against in CanLit. Twitter isn’t just allowing them to push back, but also helping other marginalized writers and allies find each other, develop community, and work collaboratively to elevate each other’s activist work and writing.

Twitter Threads as Catalysts

So why do writers thread? Perhaps for the same reason we write novels or poems—as an attempt to connect with others, to spark important conversations, and to try to change the status quo.

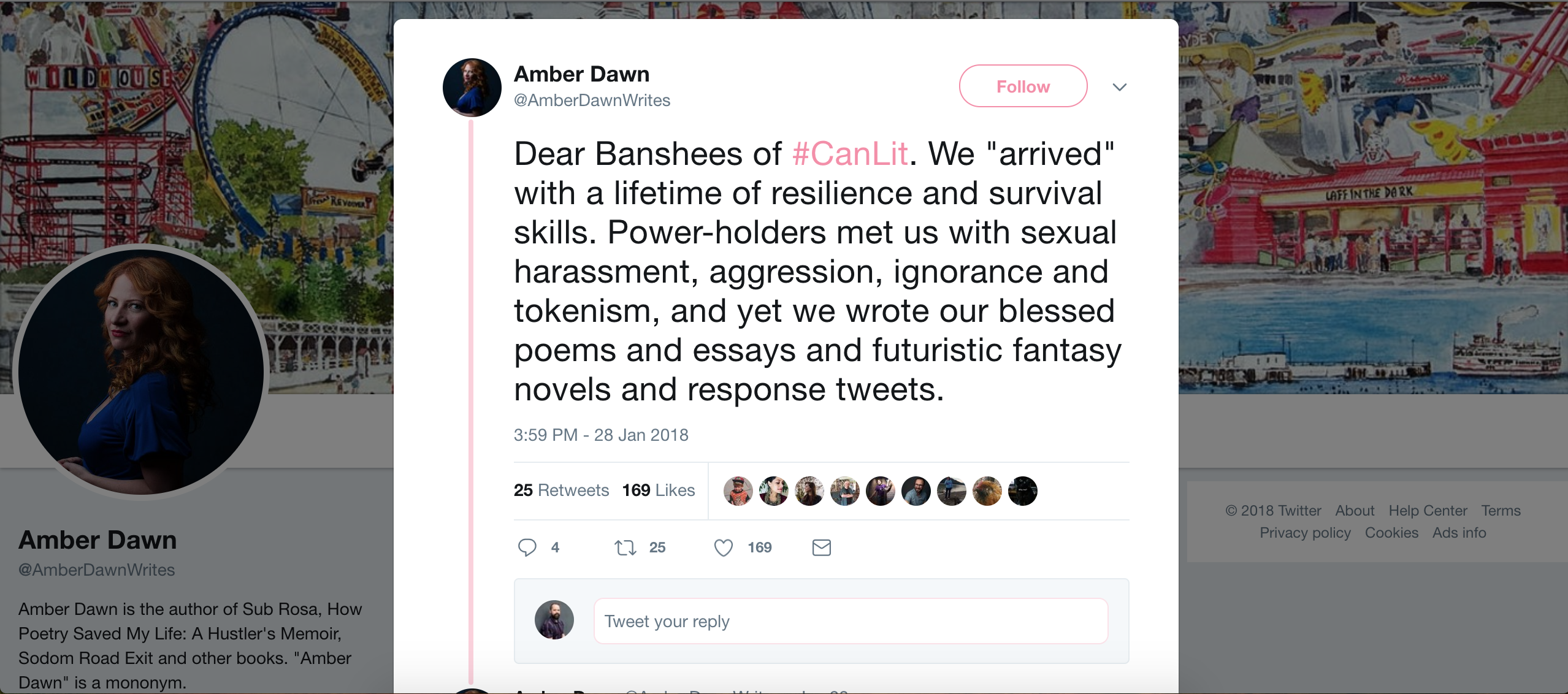

For all the talk about writers in CanLit who fight against injustices being ‘woke banshees,’ what many courageous Canadian and Indigenous writers have done in the last couple years is use Twitter essays as one way to shine light on the dark truths in CanLit.

This Twitter discourse has already created some measurable changes, but it’s also signaled the beginning of a small shift in power in the industry—that hopefully will grow over time.

As novelist Amber Dawn writes in a Twitter thread that starts off ‘Dear Banshees of #CanLit:’ “We "arrived" with a lifetime of resilience and survival skills. Power-holders met us with sexual harassment, aggression, ignorance and tokenism, and yet we wrote our blessed poems and essays and futuristic fantasy novels and response tweets. We've found, and keep finding, each other. We've spoken, and will keep speaking to power.”

If there is anything to be learned from the last two years, it is that there is value in Twitter threads. There is value in writing them. There is value in sharing them. That doesn’t mean that they don’t come at a cost—many of the writers I mention in this piece have faced consequences or harassment over their threads.

And while those that want to uphold the status quo often fight against efforts to decenter CanLit using traditional media outlets, and Twitter threads have yet to spark a major industry shift, these important essays are part of the slow and painstaking work to change CanLit. They hold the potential to continue the decentering of power in CanLit by either ‘refusing’ or breaking up with CanLit in favour of alternative ways of writing and sharing creative work, or by making more space within CanLit’s institution for those whose voices have been excluded or silenced.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

A.H. Reaume is a Vancouver-based fiction writer who reads too much and is currently in too many book clubs (four in total). Reaume has a background in feminist activism and an M.A. in Canadian Literature from UBC. She's been published in the Vancouver Sun, The Globe and Mail, USAToday.com, and Time.com and is currently trying to finish her first novel.