The Lower Reaches of Pulp

By Naben Ruthnum

It’s rare for me to be disturbed by a book: usually, I enjoy being scared or pushed to an extreme emotion within the safety of a page. But I was badly bothered by a pulp novel from the 1980s that I picked up in a Halifax charity shop.

There were many single-dose-serving paperback toughguy novels on the shelves of drugstores, truckstops, and airports from the late sixties onward. Like the Hardy Boys and Tom Swift books I read as a kid, these were series books that came out in quick succession, often from multiple authors sharing a pseudonym. You could check in with these guys and their adventures every month. At best, when the writer was great, the prose was trim and vivid, the plots spare and convincing. Richard Stark’s great Parker novels are a high watermark of this little subgenre. The novel’s title character has been played by Lee Marvin, Mel Gibson, and Jason Statham. (He was also played by Anna Karina, in Made in U.S.A, Jean-Luc Godard’s unauthorized adaptation of Parker’s adventure in The Jugger).

Most of these toughguy series are not very good. Still, many of the books are fun: as quick as a television episode, and crazily inventive when it comes to the obstacles the heroes face, even if most of the characters barely make it to one-dimensional status. While most of them are dead serious about the action and stakes on every page, the series titles reflect one of the bonus attributes of the books: they’re silly as hell. The Butcher, Hardman, The Headhunters, Dakota, Matt Helm, The Pro, Shell Scott, Nick Carter. These books reach a maximum index of gritted-teeth manliness that is as unbelievable as it is amusing.

The usual, and sometimes interchangeable, protagonist of these series isn’t the tough guy detective character we encounter in Chandler and Hammett novels and the movies that came from them. He’s a character born from the harder edges of noir and from the post-Vietnam disillusionment with America. He usually has the army, jail, or a brutal wartime background in his past. Like James Bond, he’s a fantasy projection, a guy who solves world problems and wins admiration by being great at violence. On modern bookshelves, he's still going strong in at least one form: Jack Reacher, Lee Child's series character, who regularly grabs the # 1 spot on the NYT bestseller list last when a new entry comes out. The weak box-office takings of the movie adaptation, Jack Reacher, has a lot to do with the brand of tough fans are drawn to in the Reacher novels. Tom Cruise was cast as the title character, a 6’5 giant in Child’s descriptions: the role was probably physically better suited to Dwayne Johnson, even if Cruise's screen charisma went a long way toward closing the gap. Tom simply didn't have a believable capacity for the brutal, overpowering violence that, in addition to Child’s reliably clever plotting and talent for blunt dialogue, keeps Reacher's readers coming back.

The toughguy character I’m talking about has also turned up comics from about the seventies onward. Two of these incarnations recently got the Netflix series treatment: The Punisher, of course, and the lesser-known Luke Cage, a blaxploitation-spawned superhero-for-hire with bulletproof skin and a working-class need for paid crime-fighting jobs. The genre’s move to television makes sense: the series nature of the character is part of his DNA. This is a guy who can come back and be fit into new problems, on a monthly, bi-annual, or annual basis. TV made that schedule weekly.

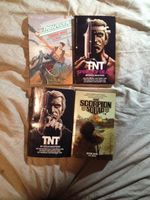

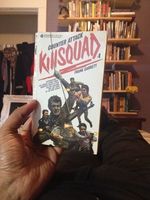

Killsquad #1: Counter Attack clearly has one of the greatest titles to ever grace a paperback cover, which is why I bought it at that Halifax charity shop. But the fun mostly stops there. The book’s a pretty clear ripoff of The Dirty Dozen, which had a maverick military commander recruiting soldiers on death row for an impossible mission against the Nazis. 1986’s Killsquad swaps out Nazis for terrorists and military prisoners for regular, if particularly violent, death row inmates. It also loses any of the characterization and stylistic elements that make the book and film of The Dirty Dozen so damn good. E.M. Nathanson’s The Dirty Dozen novel uses the tensions between the characters to get honest racial dialogue into the book, including an odd and essential subplot where a black member of the Dozen reads Conrad’s The Nigger of the Narcissus and debates its qualities with his commanding officer.

Killsquad: Counter Attack is just unrelentingly, holy-shit racist. The book begins with terrorist attacks on two planes, and from then on, any Arab character in the book is either completely dehumanized or sexualized before being blown into atoms by the squad. The author eventually runs out of racial epithets and has to improvise new ones, coining, for example, “Koran-thumper” from the insult’s Biblical counterpart.

And TNT # 1, another one of my casual selections, goes beyond the funless dumb of Killsquad and into genuinely sinister territory. It disturbed me to the point that I was handling the book as though it was a cursed object, keeping it away from food and decent human beings. Expecting the superhero / Bond fusion that TNT’s jacket copy suggested, I instead found increasingly vivid and violent sexual fantasies, with the plotting and character development agility of low-grade internet pornography.

The lack of style and skill in TNT’s rote, graphic descriptions of degradation, humiliation, and mutilation led me to a realization. This book incarnates what highbrow or moralistic readers and censors assume about the bulk of genre fiction, particularly horror: that it exists to titillate immature, sick fucks. I can’t attain the degree of irony or nihilism to take pleasure in the sadism-porn of TNT, because I can’t help but be constantly chilled by the audience that I imagine actually enjoying this humourless, flatline-prose, dominance-fantasy dreck. TNT reminded me that there are deeper reaches of pulp that aren’t trash in the entertaining, pop-culture sense, but in the sense of being pure garbage. Thankfully, crap like this makes up only a small portion of the ever-expanding, vivifying, amazing world of pulp fiction.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Naben Ruthnum lives in Parkdale, where he writes literary and genre fiction. He also writes criticism, and was last year's Crimewave columnist at the National Post. Naben won the 25th annual Journey Prize for his short story, Cinema Rex, and continues to publish widely.

Ruthnum's essay, CURRY: Eating, Reading and Race, will be published by Coach House Books as part of their Exploded Views Series.