The Same Aspirations Persist: An Interview with Cameron Anstee, editor of Apt. 9 Press

By Ben Ladouceur

In 2016, three of the five chapbooks nominated for the bpNichol Chapbook Award came from the same press, Ottawa’s Apt. 9 Press. One of those Apt. 9 Press nominees, Nelson Ball’s Small Waterways, ultimately took the 2016 prize. This is Game of Thrones-level nomination-domination, a formidable accomplishment for a single publisher. But are things like awards very important to Apt. 9 Press editor Cameron Anstee? In the interview below, Cameron lays out why he does what he does.

Open Book:

Congrats on the bpNichol win last fall. Nelson Ball’s Small Waterways is certainly a deserving chapbook. Much like Minutiae, the other Nelson Ball chapbook you published, there’s no text on the cover. No title, no author; just a little sketch. Can you tell me a bit about both of these cover images, and how they relate to their respective chapbooks? Can you also tell me about the editorial decision to forgo having any kind of text on the cover?

Cameron Anstee:

Nelson’s work is so careful and deliberate, and the space around each poem is vital. In his brand new selected poems from WLUP, Certain Details, editor Stuart Ross writes that he “sacrificed […] the effect of a tiny poem on the large white field of the page” by “greedily” including as many poems as possible given the page limitations (i.e. multiple poems on each page), but wanted to acknowledge that Nelson’s work really does need room and space on the page to feel right. I wanted to honour that in these two covers, keep it clean and simple and tidy and, I hope, right for the poems.

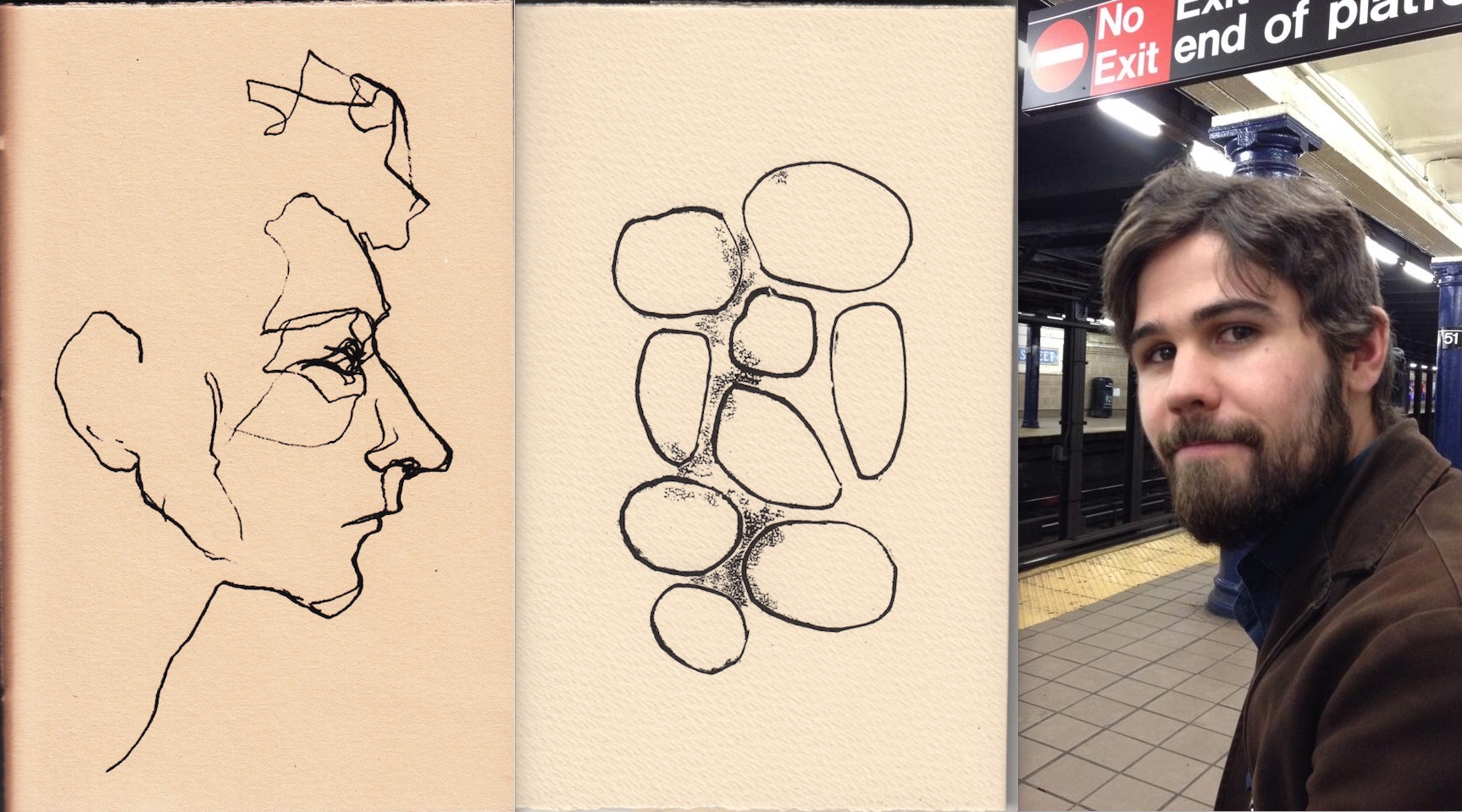

The cover of Minutiae (2014) is a line drawing portrait of Nelson by his late wife, the artist Barbara Caruso. Done in the 1960s, the portrait was originally printed and distributed (on a folded letter-sized sheet) with Nelson’s book Force Movements, published by bpNichol’s Ganglia in 1967. Using it was Nelson’s idea, something he pitched to me over email when we were discussing the book and that I was of course excited about. I tried some versions with text, but it always just felt like the text got in the way of the image. Barbara’s work is so wonderful and I didn’t want to mess it up with my amateur typesetting, so the image went alone. I can’t speak for Nelson, but I like the book-historical resonances of the cover, how it ties in to his lifelong collaborations with Barbara and with bp, how it nods backs to his first heyday in the 1960s. I also like that the point of focus of the portrait is his eye; Nelson’s poems are so much about perception, and seeing, and the effect of inhabiting those processes thoughtfully.

The cover of Small Waterways (2015) is a small linocut that I did myself. I wanted it to fit aesthetically with Minutiae (the two books are the same size), and knew it would be a simple line image on the cover stock with no text, so I did my best in my fumbling, non-artist way to get the job done. Now with a bit of distance from having done the linocut itself, and having processed seeing the image in quite a few places following Nelson’s bpNichol Chapbook Award win, I’m more at peace with it, less bothered by the bits I wasn’t good enough to do better. It is more literal than Minutiae, taking its cue from the poem “Lake Huron Shoreline, Revisited” in the chapbook: “The water has retreated / leaving stones in hard mud / / small waterways / between stones.” I will admit that I’m not great at printing linocuts and had to tidy up a few blemishes on the computer.

OB:

There’s a lot of modesty in that response. I wonder how you reconcile such a strong sense of modesty with the enormous successes of your press. Enormous is of course a ridiculous word to use because nothing is enormous in the world of small press publishing. But let’s look at the facts. Small Waterways won the biggest (and yes, almost the only) chapbook award in Canada, and merited an interview on CBC Radio One’s “All in a Day.” In addition to Small Waterways, Apt. 9 Press published three other chapbooks in 2015, two of which were also nominated for the bpNichol Chapbook Award. I’m fairly certain that it’s unprecedented for one press to take up three of the five nomination slots, and also unprecedented for this to happen for a press that published only four books eligible that year. This is not Apt. 9 Press’ first bpNichol; that designation belongs to Claudia Coutu Radmore’s book Accidentals (2011). Other Apt. 9 books have been reviewed extensively, and have sold out pretty reliably. My question is, beyond the talents of your authors, to what do you attribute your press’ successes?

CA:

It was a shock to see three books on the bp shortlist. I love all three of them, and couldn’t be happier for Nelson, Marilyn, and Lillian, but also, quite naturally, I felt self-conscious about the amount of space Apt. 9 was taking up. As you say, there is nothing “enormous” in the small press, relatively speaking, and it was surreal to speak about chapbooks on CBC Radio or to collect a huge cheque on Nelson’s behalf, but you don’t make chapbooks because you want to chase after those kinds of things. I also buy a lot of chapbooks (A LOT of chapbooks), and know how much good material is published in Canada every year by so many outstanding chapbook presses (and I can’t even begin to imagine how much amazing stuff is published that I have no idea exists). Obviously I believe in the books I publish (that would be why I put in countless hours making them), but I would never have expected three to make a single shortlist. As with all prizes, it was the right judges for the right books in the right year. Different judges, it could have been two or three books from Desert Pets, or Anstruther, or Baseline, or words(on)pages, or shreeking violet, or The Emergency Response Unit, or Puddles of Sky, or Flat Singles, or…, or..., or…., right? I’m so grateful to Hoa Nguyen and Alice Burdick for their choices, but also want to emphasize that obviously “best” is relative here. Canada’s chapbook scene is unbelievably strong, and I can’t wait to see what gets published in 2017.

As for the broader “success” of the press, I’ve been lucky. I’ve had really wonderful people trust me with their work (as well as be very patient with my pretty slow process); I’ve had other really wonderful people support the press by buying books, talking about them, writing reviews and articles and hosting readings; I’ve had a great network of support in Ottawa’s scene to learn from and with and get better alongside, as well as people in Toronto and Kingston and Peterborough and elsewhere; I’ve received a million small kindnesses from good small press people; I had a bunch of years working with In/Words Magazine at Carleton where I got to learn so much so fast and make endless mistakes. I also have an incredibly supportive partner who sits with me at book fairs and shows up at readings and listens to me go on about it all and smiles each time I drag her into another bookstore and always has constructive and insightful feedback on things I’m working on. It takes up a fair bit of space in our home, and that wouldn’t be possible without her support.

I think Apt. 9 publishes compelling books, and I work hard when making them hoping that they’ll be compelling to handle and look at as well as to read. I do it because I enjoy doing it (as I hope is the case for everyone making chapbooks), and I think that enthusiasm shows in the books and in how I talk about them and sell them at book fairs. I try to model the work I do after other presses I see doing responsible and thoughtful and good work, past and present, and hope I can keep my little corner going to support the whole unwieldy chapbook-making world as it tries to keep going.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

OB:

When you were starting Apt. 9 Press back in 2009, what other presses did you look up to? Did you aspire to achieve certain goals, or was the idea simply to make chapbooks? If there were specific aspirations then, do there remain any more to achieve?

CA:

Presses like Contact, and Weed/Flower, and Coach House were part of a historical body of influences. Of established chapbook presses, Proper Tales and above/ground were big motivators for me starting out. I have a vivid memory of seeing The Emergency Response Unit at a small press book fair in Ottawa (it must have been Summer 2009, or maybe Winter 2008?), and just being floored by what they were doing with the physical production of the books, who and what they were publishing, Leigh and Andrew’s kindness and energy. It was a push for me both to send them a manuscript (which I did, and which they took), but also to get my stuff together for Apt. 9, which was in planning stages already. During my time at In/Words, we made lots of books, but pretty often we sent stuff to a printer. I wanted to do even more of the work by hand, I wanted to stitch, and do interesting things, and learn. Ferno House was a similar push when I first saw their books, but that timeline is fuzzier, I think Apt. 9 was already a going concern. Ditto for Puddles of Sky. A dozen (conservatively) presses have emerged since Apt. 9 got going that I love and am regularly deeply jealous of.

The idea was to make books, to learn more about making books, to make nice looking and feeling books, to make books by interesting and good and challenging writers, books by emerging and established writers, to publish my friends and heroes, to publish people I’d never met, to stake out a little corner in Ottawa and try to get it into conversation with other places.

Those same aspirations persist. I also want to make books by letterpress, by rubberstamp, by silkscreen, by whatever other ways I can find. I want to collaborate with other presses. My list of people that I want to publish is already too long, and growing every day. I don’t think I could publish them all if I keep Apt. 9 going until the day I die. I’d like to do the odd-perfect bound thing going forward. If I can get myself gainfully employed post-Ph.D., I’d like to start paying writers in copies and dollars. I still want to learn more about what happened earlier in Canada, what is happening across the country now, what is happening everywhere else not-in-Canada.

I’ll keep going as long as I can, as long as it seems like Apt. 9 is making a meaningful contribution as long as I keep being trusted with manuscripts that sustain my interest across the time-and-resource-intensive process of making the books. I’ve been very lucky to have been trusted with first chapbooks, but also with manuscripts from people like Phil Hall, and Nelson Ball, and Beth Follett, and Monty Reid, and Sandra Ridley, and on and on. I’m still proud of every single book I’ve done. I’d like to keep that going.

OB:

A lot of small pressers spend their lives balancing three things: their press, their creative writing, and their primary source of income. You are, of course, no different, and it could be said that at least two of these things have come to a head for you recently. You've got a collection of poems coming out through Invisible Publishing next year, and in the time between the first and last questions of this interview, you submitted your PhD thesis. Do these three pursuits – writing, publishing, earning dough – feed or malnourish each other?

CA:

They absolutely feed each other. I see my writing, my publishing work, and my academic work as parts of a single small press practice. I really don’t think that these things can be separated, and regardless of whether I leave academia now that the dissertation has finally been submitted, I’ll still be researching and learning about small press history. You need to know what has been done to understand what is being done today, to try to contribute to what might be done tomorrow, to be a responsible contributing member of the small press community. Your question already identifies that most (if not all) small press folk take on more than one role—no one in the small press is only a writer; you’re a writer and a publisher, or an editor, or run a reading series, or do scholarship in different forms, or just show up and listen and read the books. There’s no money in any of it, so it only keeps going if people put in their own labour and sweat to fill in all the gaps, to build and maintain everything around the writing. It has to be written, published, printed, distributed, sold, read, collected, preserved, recirculated, reread, and on and on and on. Anyone interested enough to have read this far in the interview is probably straddling three or four or five of those roles today alone. So, I see each part feeding each other part, I see each as vital, and I see each as a responsibility.

OB:

What do you watch or listen to while you're sewing the books?

CA:

For a while I was burning through episodes of WTF (I especially love the shop talk about coming up in comedy; it resonates with all this small press stuff). I used to watch (mostly listen to) soccer while doing it, but we cut the cable. Radio, Spotify, my iPod. There are a pile of good poetry podcasts running now, so I expect I’ll be listening to those more when I get back to stitching books in the next month or so. Sometimes I listen back to readings that I missed (Tree in Ottawa is great about filming, and making footage available). What do other people listen to or watch? I would love suggestions.

Cameron Anstee lives and writes in Ottawa ON where he runs Apt. 9 Press. He edited The Collected Poems of William Hawkins (Chaudière Books, 2015), and Book of Annotations is forthcoming from Invisible Publishing.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Ben Ladouceur is a writer living in Ottawa. His first collection of poems, Otter (Coach House Books), was selected as a best book of 2015 by the National Post, nominated for a 2016 Lambda Literary Award, and awarded the 2016 Gerald Lampert Memorial Award for best debut poetry collection in Canada. Ben is the prose editor for Arc Poetry Magazine.