When All Your Faves Are Problematic

By Amanda Leduc

Recently, at a dinner with several writer friends, I learned that a writer I’ve long admired has been known to behave rather smarmily around young women. This writer is now on the list of names that get whispered around when people caution writers who to seek out and who to avoid in the industry. One of those people. One of those names.

I’ve read all of this writer’s work. They’ve been a favourite of mine since, well, forever. Hearing this news about them, I felt like I’d been socked in the gut without warning, or maybe not socked in the gut so much as punched in the head hard enough to see stars. An entire world shift in the span of seconds—you think you know what’s what and then, suddenly, everything you thought you knew disintegrates in the span of a few tumbling seconds.

To say I was disappointed is, well, an understatement.

*

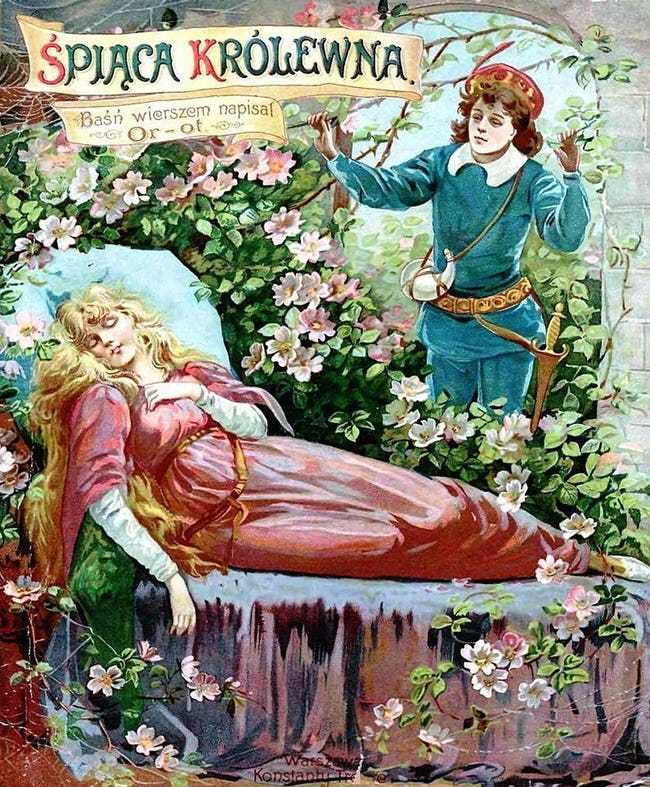

In the original version of “Sleeping Beauty”—a tale called “Sun, Moon and Talia” written by the Italian writer Giambattista Basile and published in his collected works, The Pentamerone, in 1634—a lord has a beautiful daughter who injures herself on a splinter of flax and falls into an enchanted sleep. Her father, heartbroken and believing her to be dead, lays his daughter on a velvet blanket on the throne, then boards up his castle and leaves his daughter to the wilderness. Some time later, the king passes through the land and follows one of his falcons into the abandoned castle. Seeing the beautiful woman on the throne, the king is overcome with passion. He calls out to her, but she doesn’t respond. Not one to take silence for an answer, the king “be[holds] her charms and f[eels] his blood course hotly through his veins.” He then carries her, still unresponsive, to a bed, where he “gather[s] the first fruits of love”.

Satisfied, the king then returns the (still unresponsive) maiden to her throne and leaves, and for a time he forgets the encounter altogether.

Nine months later, the woman gives birth to twins.

*

“What am I supposed to do now?” I asked my friends, the night that I found out about The Writer. As I asked it, I could feel distaste flickering at the memories of the books that I had read, already threatening to spread over the memories that I had of the stories that they held. Those beautiful, gorgeous books that had shown me so much about loyalty and beauty and mythology and love. They were dimming already. “Do those books all just go right into the fire?”

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

*

Eventually the king remembers the woman in the abandoned castle. He takes another hunting party and returns to the enchanted place, expecting (one assumes) to find an unresponsive, pliant woman, but instead finds Talia nursing her twins. (When they are first born, the twins are attended by two fairies, who place each child at their mother’s breasts. One of the babies manages to get a hold of the woman’s finger and sucks on it, dislodging the flax splinter and waking the mother from her sleep.)

The king is overjoyed but cannot take the woman and the children home because, of course, he is already married. He spends a few days with Talia and the babies and leaves, promising to return and bring them back to the kingdom. His wife, who has grown suspicious in her husband’s absence, gets the truth out from a hunting party member when the king returns. She sends for the children. Talia, thinking that the king has summoned them, gladly lets the babies go, whereupon the queen welcomes them in to the castle and tells the cook to take the twins and kill them.

It can be a difficult thing, grappling with the realities of a story that you thought so highly of and loved so well. What was once a story of magic and dragons turns out, in fact, to be a story about a different kind of dragon altogether—one at once ancient and modern, a beast both terrifying and disappointing precisely because it isn’t magical at all. A story about a sleeping princess, a story about a king who in the end is just a person, and not a very nice one at that. A story about a writer who is also, in the end, just a person—and apparently not a very nice one at that, either.

What, exactly, is one to do? Do we forget the old stories that we knew and loved in light of what we’ve learned? Arguably, “Sleeping Beauty” has always been problematic, even the brighter Disney version that most of us know. Three mischievous fairies, a gown that plunges from blue to pink and back again. A clueless princess who is brought back to life with true love’s kiss, her destiny secured because of the kindness and strong hands of an attractive prince. Put the two of them together and the gnarled roots of the original story creep forward and twist around the new version, forever altering it. Suddenly you can see the connections—from blatant misogyny to misogyny that runs under the surface, from a man exerting overt power over an unconscious woman to another man, exerting power under the guise of romance and true love. You’ve seen the original version now. There’s no going back.

What to do, then, with the knowledge that a writer—or director, or politician, or any previously beloved public figure—one has admired is a rather unsavoury person underneath it all? How do you come back from that? How do you make sense of the connections between their behavior and the stories that they tell, especially when they’re telling stories and creating art that you still love?

*

The cook in the old tale cannot bring himself to kill the twins, and so he brings them home to his wife and they hide the children away. The queen, thinking that the children are gone, summons Talia to the castle. When she arrives, the queen proclaims that she’ll be put to death for seducing the king. Talia screams for the king and he hears her; when he comes into the chamber and sees the two women, the queen confronts him about the infidelity. She is incandescent with rage, but because this is a fairy tale, her rage turns her into a villain. The king, thinking that the queen has murdered his children, orders her thrown into a fire. After she dies, the cook comes forward and confesses that the children are safe.

The king, overjoyed, marries Talia, and the family lives happily ever after.

*

It probably sounds strange to compare a version of a fairy tale that no one knows anymore to the question of whether or not to let go of art. But I held on to the tale of Sleeping Beauty because I wanted to believe in the magic of the new version—the brightened Disney colours, the laughter, the joy. I held on to the books of the writer that I loved because I wanted to believe in those books too—in their goodness, in the way that the goodness they speak to can somehow obscure or mitigate the darkness of the tales about the author themselves.

The reality, of course, is that none of this is true. I won’t be reading any more of this author’s new work. The sentimental part of me wants to say that I’ll revisit the old books, the ones that I have loved, with an eye to what they brought me years ago, but I probably won’t do that, either. They have been changed now, grown over with new knowledge. They’ll never read the same to me again, no matter how much I might wish it.

*

People often argue that you can’t judge the merits of art on the basis of its creators. Tolkien was a racist, so was Dr. Seuss. Does that make all of their art bad? “If we cancel X, what’s next? Why don’t we cancel everything? If we’re canceling art on the basis of artist behaviour, where does it stop?”

Here’s the thing: I believe in the power of art to reach across boundaries and touch people no matter the nature of its creator. But there is so much art out in the world. There is so much art out there that hasn’t been written or painted or produced by someone who is racist. There are tons of novels out there written by people who do not engage in questionable behaviour that gets whispered about in backchannel conversations.

So perhaps a better question to be asking is where does it start? When you shake off old fairy tales and beloved books from your past because the people who created them turn out to be less than stellar, what’s left out there to discover?

A lot, as it turns out. I left those beloved books of mine behind last year, and in the place of those re-reads, I discovered several new authors that I might not otherwise have encountered. New authors and new stories that are already classics for me, fairy tales that are so much more interesting than a story about a woman who pricks her finger and then is raped while she’s unconscious.

I’m not saying that there isn’t a place for stories like these—we can certainly learn a lot from “Sun, Moon, and Talia”, not least of all the knowledge that fairy tales were problematic long before Disney tried to clean them up—but rather that we shouldn’t limit ourselves to the stories that we’re told are classics, especially when we learn that those classics come to us from people with significant failings. The world is much greater than Sleeping Beauty in all of its versions; the world is certainly greater than Tolkien or Dr. Seuss, and it is greater than the artist who will show themselves to be the next unsavoury character in line.

Where does it stop? It doesn’t stop anywhere.

It begins right here, with the author you have yet to know.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Amanda Leduc is a disabled author with cerebral palsy whose stories and essays have appeared in publications across Canada, the US, the UK, and Australia. Her first novel, THE MIRACLES OF ORDINARY MEN, was published in 2013 by Toronto's ECW Press, and her new novel, THE CENTAUR’S WIFE, is forthcoming with Random House Canada. She lives in Hamilton, Ontario, where she serves as the Communications and Development Coordinator for the Festival of Literary Diversity (FOLD), Canada’s first festival for diverse authors and stories.