Bee Whisperer Jenna Butler Talks from Her Off the Grid Alberta Farm about Climate, Storytelling, & Healing

In recent years, we've learned to look to the bees as a metric of our world's failing health, and the results haven't been heartening. But there are those who are doing the work to support these essential insects and pollinators that effect the entire, interconnected environment we live in and depend on.

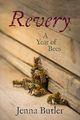

One of those people is author Jenna Butler, who, for more than five years, has worked with bees on her Northern Alberta farm. The experience led Butler, a decorated poet and essayist, to write Revery: A Year of Bees (Wolsak & Wynn), her memoir of working with and learning from the bees.

She takes the reader into the cold, crisp land she shares with them, weaving the realities of contemporary farming, the worlds of bees both wild and honey, and the environmental impacts of Alberta's changing approach to agriculture together with deeply personal storytelling.

At its heart, Revery is about hope in the face of despair, and how small and dedicated work can build something beautiful, much like the work of the bees themselves. And so we're excited to welcome Jenna to Open Book today as part of our True Story nonfiction interview series. She tells us about living off the grid in the boreal forest, the therapeutic value of seeing something green (however small) while writing, and how she uses discouraging moments to sparks her to action, both literary and environmental.

Open Book:

Tell us about your new book and how it came to be. What made you passionate about the subject matter you're exploring?

Jenna Butler:

Revery: A Year of Bees (Wolsak & Wynn, 2020) is about beekeeping in the northern boreal forest of Alberta. It’s a story of hope, of coming to understand more fully a connection and responsibility to place and ecology. It’s also a story of recovery from trauma, and how a deep relationship with the bees and the land on which they live helped me to find my way through a kind of violence that threatened to break me.

I live off grid in the boreal forest, and my husband and I are grateful to work with land we profoundly respect and learn a great deal from. We’ve been keeping bees for five years now, and the book chronicles our journey, as well as our continually deepening sense of place and the boreal ecosystem of which we’re a part. I write about the world I live in and engage with daily; it’s the same focus that permeates my teaching.

OB:

What do you need in order to write – in terms of space, food, rituals, writing instruments?

JB:

I don’t need much! Over the years, I’ve come to be able to write whenever and wherever I am; I think this comes from almost two decades as a teacher, where writing time is at a premium, and you have to take it where you can find it. So – at the old dining room table in the light from the big windows, or at my desk in our small shared study, or out in the evenings by the firepit, watching the dusk coming down. I love to have a cup of tea at hand (though it’s usually gone cold before I remember to drink it).

I almost always write on the laptop, instead of by hand. Old injuries in my hands are turning arthritic, so writing by hand is something I keep mainly for correspondence these days.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

I write best where I can see something green and growing. Here at the farm, that’s not a stretch, but even when I’m writing in the city, on a train (in the days before COVID), or where have you, the smallest scrap of green will do. Clover pushing in around the foundation of a building. A tree rootling up through concrete. There’s home for me in that.

OB:

What do you do if you're feeling discouraged during the writing process? Do you have a method of coping with the difficult points in your projects?

JB:

Ha, I felt so discouraged at times when writing Revery because I was looking at climate grief, and at solastalgia, and I couldn’t see the slightest path through. But with good advice, I got around that discouragement through careful action. I mean, I can’t possibly reverse climate change as a single person, but I can take meaningful small actions here at the farm: planting trees to sequester carbon, ensuring that our practices stay organic and mainly human-powered to avoid large polluting farm equipment and tillage, and closing loops in seed saving and food security to cut down on air miles. I guess I’d extend this to my writing process in general: when I get discouraged, I take action. Sometimes, this is as simple as switching gears, as we do, from writing itself to other activities that support the project (listening to music that informs the project, researching, discussing and collaborating with friends, connecting with community). Most importantly, I remind myself that these activities are also a kind of through-writing. I give myself permission to fill up for writing my way through a discouraging spot by doing things that might not look exactly like writing, but are filling my tank nonetheless.

OB:

Do you remember the first moment you began to consider writing this book? Was there an inciting incident that kicked off the process for you?

JB:

From our very first summer as beekeepers, I knew I wanted to write about our growing relationship with those hives, but I wasn’t certain what shape the manuscript would take yet. I explored writing about women beekeepers only; I researched women beekeepers around the world and the communities they supported through their beekeeping efforts. Ultimately, though, I realized that I wanted the book to be about the place I call home, Alberta, and I wanted to situate the honey industry as a parallel, lesser-known story alongside that of the usual oil-and-gas narrative about this province I love.

I knew that I didn’t yet have a firm enough relationship with the bees to consider writing a book at that point; it took several years of meeting the bees, of observing them and supporting them and planting for them, and of coming to meet and know the many wild bees already here on the farm, before I felt I had enough of a grounding to begin writing from.

OB:

Did you write this book in the order it appears for readers? If not, how did it come together during the writing process?

JB:

Ha, no, the book appeared in a very different order to begin with. I started by alternating a personal chapter with a more academic, research-based chapter, but that created a strange sort of tone-jumping that just didn’t work.

I spoke at length with Noelle Allen, the publisher at Wolsak & Wynn, and she suggested doing something I’d tried in an essay in a previous book: using the calendar year at the farm, with its associated tasks and growth, as the framework for the collection. This time, we determined, the book would track the beekeeping year in northern Alberta, and with that framework in place for the key essays in the book, the additional research-based pieces fell naturally into those spaces where they best belonged within the seasonal cycle. This reorganization of the book really appealed to me: fitting the research-based essays into the organic seasonal framework was so enjoyable and felt right. I teach about the land, and I write about it, but I live closely with it, too, and shifting the academic pieces into a seasonal, growth-focused structure felt like a better alignment.

OB:

What are you working on now?

JB:

Currently, I’m working with my students so we can all get through this last school term of 2020 (mostly) in one piece, but I’m writing toward something in my head. My friend Yvonne Blomer and I did a great deal of collaborative writing this past year on women’s desire paths in various environments (rural, urban, and internal desire paths), and I’d very much like to continue this work with her.

I’m also increasingly interested in IBPOC experiences of land and nature in Canada, especially in regard to seedkeeping, growing, farming, and land guardianship. What are some of the knowledges shared in IBPOC communities in regard to growing and harvesting? What are some of the blocks experienced by coloured bodies wanting to go into fields like agriculture? How do experiences of the land and access to the land differ for coloured and white bodies? I’m coming to these questions and these stories as a coloured woman who is also a small-scale organic farmer, a seedkeeper, a herbalist, and an academic – identities that are so often forced into conflict with one another.

____________________________________________

Jenna Butler is the author of three critically acclaimed books of poetry, Seldom Seen Road (NeWest Press, 2013), Wells (University of Alberta Press, 2012) and Aphelion (NeWest Press, 2010); an award-winning collection of ecological essays, A Profession of Hope: Farming on the Edge the of Grizzly Trail (Wolsak and Wynn, 2015); and a poetic travelogue, Magnetic North: Sea Voyage to Svalbard (University of Alberta Press, 2018).

Butler's research into endangered environments has taken her from America’s Deep South to Ireland's Ring of Kerry, and from volcanic Tenerife to the Arctic Circle onboard an ice-class masted sailing vessel, exploring the ways in which we impact the landscapes we call home. A professor of creative writing and environmental writing at Red Deer College, she lives with seven resident moose and a den of coyotes on an off-grid organic farm in Alberta's North Country.