Brittany Luby's New Picture Book is a Love Letter to the Natural World and Anishinaabe Family Life

Mii maanda ezhi-gkendmaanh/This Is How I Know (Groundwood Books) by author and academic Brittany Luby (illustrated by Joshua Mangeshig Pawis-Steckley) is warm, colourful story-poem for young readers that weaves together Anishinaabemowin and English. The Anishinaabemowin text was crafted by Alvin and Alan Corbiere, a father and son team.

In the book, a young Anishinaabe girl and her grandmother explore each season and its unique wonders, showing the beauty of each different time of year. From swirls of bright flowers to plump mushrooms and more, Mii maanda ezhi-gkendmaanh/This Is How I Know offers a great way to discuss colours, seasons, and the natural world with the young readers in your life. And Pawis-Steckley's rich and inviting artwork pairs perfectly with Luby's song-like lyrics, which draw warmth and authenticity from the childhood memories that inspired them.

We're excited to welcome Brittany to Open Book to talk about her newest book as part of our Kids Club series, where we talk to writers of books for young people. She tells us about the online tool that is her go-to writing aid, what words should taste like, and, of course, how pink puppy tummies featured in her writing process.

Open Book:

Tell us about your new book and how it came to be?

Brittany Luby:

I had the most horrendous break-up. I also had the most horrendous haircut. Nevertheless, I managed to drag myself to the most nourishing meeting with my agent, Jackie Kaiser, and the editor of Encounter (my first children’s book), Susan Rich.

At the beginning of our conversation, I didn’t feel like I could do much of anything (like get a decent haircut or create). Luckily, these two brilliant women prompted me to talk about writing. They asked me what I would write about home. I would write Mii maanda ezhi-gkendmaanh/This Is How I Know. I would write about the Plant and Animal teachers who remind me I am never alone.

OB:

Is there a message you hope kids might take away from reading your book?

BL:

I carry many hopes for Mii maanda ezhi-gkendmaanh/This Is How I Know – but, I will share just two.

First, I hope that families feel encouraged to (re)connect with the natural world, to practice close looking. As an Anishinaabe woman, I have been taught that my Plant and Animal relations are teachers. By forging relationships – through observation – with the other-than-human world, we can learn how to care for ourselves.

In The Four Hills of Life: Ojibwe Wisdom, Thomas Peacock and Marlene Wisuri explain, “We know winter is approaching when birds flock together in the fall. We know winter will be long and cold if bears dig deep dens and squirrels store large quantities of seeds and nuts.” Mii maanda ezhi-gkendmaanh/This Is How I Know invites us to follow a granddaughter and her grandmother as they associate different seasons with different other-than-human beings and star signs.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

Second, I hope that readers – Indigenous and non-Indigenous – feel the love and warmth that can fill Anishinaabe households. Headlines in mainstream Canadian media tend to emphasize the challenges faced (rather than the successes celebrated) by Indigenous families. It is true, as Indigenous Services Canada writes, that “52.2% of children in foster care are Indigenous, but account for only 7.7% of the child population.” But, we also need stories like This Is How I Know and Richard Van Camp’s May We Have Enough to Share that show us that culturally-appropriate care enriches life.

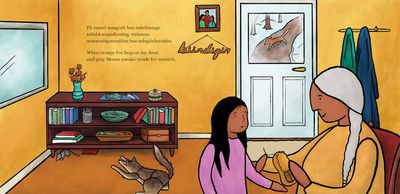

I encourage readers to look closely at the spread with Fox and Mouse. Here, a grandmother beads moccasins. A family portrait hangs in the background – just above an Anishinaabe sign that invites readers to come indoors (biindigen). A quillwork box sits on the bookshelf beside a smudge bowl. Here is a girl whose days are rich with kin and culture.

OB:

What was the strangest or most memorable moment or experience during the writing process for you?

BL:

I first envisioned This Is How I Know as a board book. This helps to explain, in part, the emphasis on colour. I wanted guardians to be able to scale their reading practice from teaching seasons to teaching colours to getting outdoors and spotting red-capped woodpeckers.

I read teaching blogs and parenting blogs to try to identify which colours are most commonly taught to preschoolers. Pink is one such colour. You may have noticed phrases like “rosy pink cheeks” in the picture books on your shelf.

I did not want to draw attention to Indigenous bodies in the text. Dr. Ian Mosby's research makes clear that our ancestors were tested on in the name of scientific progress. The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Woman and Girls (Volume 1a) reveals how Indigenous women and girls have been exotified by colonial onlookers (386-391). Stereotypes about sexual availability have, in turn, resulted in violence. There would be no “pink cheeks” or “red lips” in Mii maanda ezhi-gkendmaanh/This Is How I Know. And so, I struggled to write pink into the book.

One slow morning, during a visit home, I decided to write at the kitchen table. Dad popped into the kitchen to refill his coffee. “Whatcha working on, Kiddo?” he asked. The floodgates opened. I explained my predicament. I also spoke about how I didn’t want to limit colours like pink and purple to the flowers of summer.

Dad took a sip and then said, “What about a puppy’s pink tummy?”

This felt like a solution – but, I hadn’t looked too closely at our puppy’s belly. “But, are they pink?”

“Yep.”

I googled it.

Dad was right. He solved the “pink puzzle” over a cup of coffee – in one memorable moment.

OB:

What do you need in order to write – in terms of space, food, rituals, writing instruments?

BL:

When I am writing for children, my favourite online tool is Text to Speech Reader (TTS). Because children’s books are written to be read aloud, I feel it is essential to hear drafts. If a passage is unintelligible to me when read by "English, UK, Female" or "English, US, G," I revise it.

While I use TTS to mimic the listener's experience, I read aloud to mirror the reader's experience. Words, I believe, should “taste delicious” (or feel good in the mouth). If a sentence is difficult to "chew," I rewrite it.

This part of my process is very private. It requires a certain vulnerability - a willingness to sound out solutions. It is no secret what I am doing. Every now and again a passing family member will ask, "Are you talking to yourself?"

"Yep.”

OB:

What are you working on now?

BL:

I am working on a new picture book tentatively titled Stars for Ojiig (which has been signed by Little, Brown Books for Young Readers).

Stars for Ojiig follows an Anishinaabe boy from the reserve to the city after his father receives a government job. Ojiig struggles to adjust to his new surroundings. Over time, parental support and cultural activities help Ojiig to make the city feel like home.

This story was inspired by my own move from Treaty #3 to Gunshot Treaty Territory. I travelled over 2000 kilometres southeast to attend university. A friend, Leanne Ochapowace, gifted me with a star blanket before the journey. It was made with calming pastel colours. I carried it with me for years.

Leanne, if you read this, miigwetch. Thank you for the care and for the inspiration.

I am also doing a virtual tour of Dammed: The Politics of Loss and Survival in Anishinaabe Territory, a history book for adult readers. This text reveals how hydroelectric development upset Anishinaabe relationships to Plant and Animal teachers – including Duck (who appears in Mii maanda ezhi-gkendmaanh/This Is How I Know) – in my ancestral territory. More than that, it shows how Anishinaabe families responded creatively to manage the government-sanctioned environmental change and survive the resulting economic loss.

__________________________________________________

Brittany Luby, of Anishinaabe descent, was raised on Treaty #3 Lands in what is now known as northwestern Ontario. She is an assistant professor of history at the University of Guelph and an award-winning researcher who seeks to stimulate public discussion of Indigenous issues through her work. Her debut picture book, Encounter, illustrated by Michaela Goade, received wide acclaim. Brittany currently lives on Dish with One Spoon Territory.

Joshua Mangeshig Pawis-Steckley is an Ojibwe Woodland artist and a member of Wasauksing First Nation. His work aims to reclaim and promote traditional Ojibwe stories and teachings in a contemporary Woodland style. He works mainly in acrylics, digital illustration and screen-printing, and has had several solo art exhibitions across Turtle Island. This is his first picture book. Joshua spends his time living between Vancouver and Wasauksing First Nation.