Filling in the Blanks: Photography, Inspiration and Max Dean’s Albums

I have an album. It isn’t mine, but I am taking care of it. For how long, I’m not sure. I’m not even sure for whom.

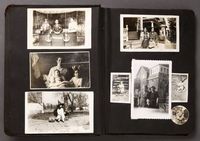

The album tells a story, but the narrative is fragmented. It’s set in the US in the 1940s and ’50s. There’s a man named Richard, who wears a fedora, trench coat and a mischievous smile, and moves west to California, where he falls in love. He brings his bride back to the Dorick farm, which is somewhere in the east, although I don't know where. There’s a black farmhouse, and then the black farmhouse has been painted white, and then the crumbling farm fixtures have been replaced with newer ones. There are two boys, Pete and Brook — half-siblings, I think — a dog named Timmy and “Mum” in a flower bed bursting with pink chrysanthemums.

I wish someone could fill in the gaps. I wish I knew who put the album together — the unidentified narrator, who wrote the cheeky annotations. On the pages after Richard brings his bride back home to the farm, for example, he or she wrote, “Good-bye black house! Good-by (sic) carefree days! There’ll be some changes made — under new management.”

But I may never find out.

As a writer, I have always loved old photographs and how they transport you back to a time and place, but without all of the details, leaving room for the imagination to roam. For this reason they are sometimes used as inspiration for flash-fiction contests, such as Geist’s postcard contest, or in creative writing classes. Toronto writer Sarah Selecky’s e-course, Story is a State of Mind, includes three photographs by Helene Cyr, intended to help students start writing a story or scene; at the University of Pennsylvania, writer Paul Hendrickson is teaching an entire course about writing non-fiction narratives from photographs.

When I heard about artist Max Dean’s Album exhibit at the AGO, and how Dean was giving away many of the 600-plus albums he’d collected over nearly a decade, I didn’t hesitate. One afternoon in May, I stopped by the Foto Bug, a suped-up Volkswagen parked outside of the AGO and filled with Dean’s albums, which had been sorted, labelled and packaged into cream-coloured boxes for the purposes of giving them away.

The first two albums I picked up were from the 1910s or ‘20s — historical texts, certainly, but somehow not for me. The third was a bit of a mess, a heavy blue album with loose pages, many of its tiny black-and-white photographs falling out. Over two-thirds of the pages were blank. But somehow, it was perfect. All I had to do to make it official was sign it out and pose for a photograph: I was now the album’s custodian.

I carried it around with me for the rest of the day — to the park, where I celebrated a friend’s birthday, then to an Indian restaurant for dinner. It wasn’t until I spent some time alone with it that I became engrossed in its story. It turns out, I was wrong about what a random stranger’s album would offer me. It wasn’t ripe for fictional mining. It was already a book, with characters, setting, and a plot.

When I explained this to Dean on the phone a few weeks later, he told me the story of Album’s origins. In 1993 he was planning a new installation called As Yet Untitled (which is now part of the AGO’s collection). The piece would involve an industrial robot that would pick a family photograph out of a hopper and offer it to the viewer. If the viewer didn’t intervene or if there wasn’t anyone standing there, the robot would feed the photograph to a shredder. The project would require tens of thousands of photographs.

Dean was visiting Seattle, so he stopped by the famous Pike Place Market, where he found three albums and some loose photographs. “I remember coming back to the hotel and sitting in the lobby of the hotel and looking through the albums,” he says. “My intention at that point was to cut the albums up and use them as material for this particular work. After I got into the first album I knew that wasn’t going to happen. They were just amazing books.”

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

The difference between individual photos and photo albums, Dean says, is the level of intention on the part of the album’s creator. Creating an album involves selecting photos, sequencing them, possibly writing captions and so on. “I think they’re unconsciously telling a story,” he says. “And I think it’s remarkable. This is probably the first and only book people will ever make.”

Dean continued collecting albums for eight or nine years after As Yet Untitled was finished. He stored them in his studio, in banker’s boxes. About two years ago, thinking of moving and still uncertain about what to do with his collection, Dean contacted his friends at the AGO. Album grew out of discussions and many visits from curatorial staff, who selected about 225 albums for their collection and with Dean devised a plan to give the rest away to “custodians” to care for.

They have since given away some 400 albums to about 385 people. Others are on display in an AGO exhibit that ends September 9, giving visitors a unique opportunity to peer into the everyday lives of others. The subjects range from stoic families in the 1910s and ‘20s to travels in Gaspé, Quebec in the ‘30s to German parties in the ‘50s and beyond.

The project has a Facebook group, used by Dean, AGO staff and custodians to share photos, details and updates about their albums. Twice albums have been reunited with their families — in one case with help from the AGO and in the other thanks to an enterprising custodian. In both cases, the family members have reported back through the Facebook group, keeping the project alive.

Facebook also happens to be the place where most 21st century photo albums are created, stored and shared — a detail that is not lost on Dean. What’s interesting, he says, is how the storytelling aspect is preserved. With a traditional photo album, its creator would probably sit down and narrate the album’s story to friends or family members, who would probably make comments as they flipped through. But if you separate the album from its owner, as has been the case with all of these albums, that process disappears.

“We’ve lost the narrator in most of these,” Dean says. But not so on Facebook — there both the narrator and the commenting process are preserved.

Although he's enthusiastic about Facebook's potential, Dean thinks the excitement about Album has reminded people of the value of doing things the old-fashioned way — and that their online photo albums exist only in the ether.

“People realize the book itself has a physical presence in the world,” he says. Now more than 600 albums lighter, he would know.

Nicole Baute's writing has appeared in the Toronto Star, Toronto Life and The Feathertale Review. She is co-editor of EAT IT: A literary cookbook of food, sex and feminism, scheduled for release fall 2012, and blogs about writing here.