Meet Chef Shane M. Chartrand & Sample Original, Mouth Watering Recipes from tawaw: Progressive Indigenous Cuisine

In Cree, "tawâw" means "Welcome, there is room". Chef Shane M. Chartrand couldn't have chosen a more appropriate title for his show-stoppingly gorgeous new cookbook - not only in the mouth watering recipes he shares, but the moving and inspiring stories, interviews, and photographs he includes from his cooking journey. Visually arresting, the book is also packed with photos of Chartrand art-like creations and a whopping 75 recipes to allow readers to recreate his beautiful meals at home.

We're incredibly excited to present a lengthy excerpt from tawâw: Progressive Indigenous Cuisine (House of Anansi), which Chartrand wrote with Jennifer Cockrall-King. Courtesy of House of Anansi, the excerpt includes not only two incredible recipes (Yellowfin tuna with seaweed salad and glass noodles, and salt-roasted beet and goat cheese salad with candied pistachios), but also Chartrand's introduction, where he speaks about growing up, hunting, connecting with his community, and his early days working in kitchens and learning to combine flavours and develop his signature style.

tawâw represents 15 long years of research, cooking, recipe development, discussions with fellow Indigenous food lovers, and more. It's the rare cookbook that feeds the body and the soul, and we're honoured to present a teasing taste of it on Open Book.

Excerpted from tawâw: Progressive Indigenous Cuisine by Shane M. Chartrand with Jennifer Cockrall-King:

Introduction

tawâw [pronounced ta-WOW]: Come in, you’re welcome, there’s room.

What does it mean to be an Indigenous person who is an executive chef in charge of his own professional kitchen and staff? What does it mean to have cooks from different Nations working for me, looking for guidance on how to express their ambitions, their dreams, and their identities through food? How do I create — one dish, one menu, one dinner at a time — a progressive Indigenous cuisine? Not an historical re-creation but a cuisine that reflects who I am and how I live with one foot in the Indigenous world and the other in the non-Indigenous world? I’ve been asking myself these questions for the past 10 years — half of my professional cooking career. tawâw is my personal record of exploring these questions through conversations, education, and cooking with family, friends, and the culinary community I am proud to be a part of.

My birth name is Shane St. John Gordon. But for the first three decades of my life, I didn’t know this fact. I also didn’t know the names of my birth parents or my home Nation. I was a part of a large group of Indigenous children in Canada who were taken from our biological parents, placed into foster care, and then put up for adoption from the early 1960s through to the mid-1980s — what is now known as the “Sixties Scoop.” I was given up when I was a year and a half old and was in foster care for five years. Though I was so young, I remember being alone, moving from place to place, and I remember being hungry. In those early years I didn’t have a lot of food. I wasn’t starving, but I remember being hungry all the time. That’s really my earliest memory.

When I was almost seven years old, I was moved to the home of Belinda and Dennis Chartrand. They fostered a lot of children over the years, but of all the kids who went through their house, they chose to adopt me. I’m one of the lucky ones because I have an incredible and loving family. My mom, Belinda, is of Irish and Mi’kmaw descent. My dad, Dennis, is Métis. I have an older sister, Rae; an older brother, Ryan; and a younger sister, Erin. It took me a while to get to know my siblings, as I was the only adopted child in the family. This is how I came to have a Métis family.

Our home was on an acreage midway between the cities of Calgary and Edmonton, in the province of Alberta. I went to River Glen School, a public school in Red Deer. I was the only Indigenous kid at the school. There was one black kid and one Mexican kid, but I was the only kid who identified as “Aboriginal” — the word we were using in those days.

As a family, we sat around the table and ate dinner together every night. It wasn’t what I was used to from my time in foster care. That might seem sad for some, but it wasn’t for me since I didn’t know better until I got adopted. Only then was I introduced to good food, sitting with family, and rules.

My mom’s cooking was very simple, but keep in mind there could have been 10 or 12 foster kids living with us at any time, and my dad was often on the road for work. Mom used to cook up big pots of stew, chili, and soup. I loved her goulash, cabbage rolls, and spaghetti and tomato sauce. And she made this really great pistachio pudding dessert with whipped cream and marshmallows that I absolutely adored, too. It was so “of its time” but pretty damn delicious. My mom likes to tell me that I always said “thank you” after each meal — and that I was the only kid at the table who did.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

My dad went hunting a lot — so much so that we got sick of eating moose meat! Mom and Dad had about five or six acres of land. We had a barn and a long log home. There were horses, chickens, ducks, rabbits, and geese on the property. And there was a beautiful farmer’s field behind the house. Nowadays, I would build a cob oven or smokehouse there, but Mom and Dad sold the property a number of years ago. It was a lot for them to keep up.

So much happened in that back field — everything from Dad teaching me how to drive our van, to just being a kid doing ridiculous kid-things, to simple gardening. Oh, the amount of gardening we did was just incredible! We grew turnips, potatoes, carrots, onions, and rhubarb — normal stuff, nothing crazy. And we had a beautiful root cellar that my dad, my brother Ryan, and I built together. Mom did a lot of pickling. You’d walk in the house and the smell of vinegar would be so strong. She made the best pickles ever. (Of course, right?)

I guess you’d say Dad grew up poor. His family’s house didn’t have any electricity and there was only an outhouse for a bathroom. So his big thing was saving money and being frugal. He’s retired now, but in his working life he was a mechanic and a welder. He can fix anything. He built a chicken-plucking machine. Our garage always contained a vehicle he was working on. He’d be replacing an engine, and there would be a deer hanging right beside the car, ready for butchering.

We raised geese, ducks, and chickens on our acreage. It was always my job to chop their heads off. I didn’t realize it until I was older, but my dad is actually a really emotional guy. I didn’t see that because he was also very strict and serious. It was only as an adult that I figured out Dad made me slaughter the birds because he couldn’t do it.

When we went hunting, it was always about getting food for the table. It had nothing to do with taking pictures and proving who is the coolest hunter, like it is today. Through hunting, Dad started teaching me about our culture. He’d tell me, “I need your roots to always be there as an Aboriginal, and I’ll do the very best I can to make sure that you are in touch with your First Nations’ ties.”

One of the things I love most about my dad is that he has great hunting stories, even when he exaggerates them a touch. And some of my favourite memories as a kid are when Dad would take me on long “survival” trips. They could be anywhere from two weeks to a month. (Two weeks really isn’t a survival trip, but one month certainly is.)

When I was 16 years old, Dad took me and my cousin on a trip to the mountains for a few weeks. Dad made us pack on our own, but he inspected our packs in secret and then hid the things that we’d forgotten in the Jeep. (The idea was to teach us how to pack properly and be self-sufficient. Did we have the right knife? Not the biggest knife, not the smallest or lightest knife, but the right knife?) We spent three weeks out in the mountains and ate goofy things. I remember him teaching us how to cook squirrel over a fire.

When I was younger, I wanted to be a cabinetmaker. I also wanted to be an actor, an artist, or really anyone in the visual arts. Cooking as a career happened sort of by chance.

When I was about 14, I asked my mom for money to buy something ridiculous — as kids do — like a pair of sneakers. Her response was that I could buy whatever I wanted but first I’d have to find a job. So I jumped on my bicycle and rode out to the highway and applied for the first job I could find. I started as a dishwasher at a 60-seat truck stop attached to a gas station called Pumper’s Cafe. A year and a half later, I was promoted to short order cook. I’m very proud to have worked at a truck stop — most of the menu items were made from scratch — and it was a lot of fun. It’s where my career started. It’s a part of my history.

I tried to impress my parents with my cooking skills, but Mom and Dad didn’t really like me cooking at home in those days. I wasn’t all that good, to be honest. I was really just starting out. I wanted to learn more. But there was no Food Network. And I was often trying to make things that were beyond my skill level. I knew I wanted to get better. That said, it took me years just to get good.

I dated a girl for three or four years when I was quite young and skinny (I weighed 120 pounds at 18 years old). Her mom was a great cook. She made sure we sat down every day to eat together, even though I was just the boyfriend. What impressed me most was that nothing repeated during the week! This is how little I knew about cooking at the time — planning a series of meals that didn’t repeat was a revelation. I remember thinking, Did she seriously go to the store and plan the whole week of meals? How do you plan that?

When I moved from the acreage to Edmonton, there was a lot of talk in the food world about “eating local.” I didn’t understand what that meant because at my parents’ home, that was a normal thing. It was what I had to do on Saturdays: work in the garden, kill the chickens, kill the geese, kill the ducks. My family taught me to have a lot of respect for food when we’d go hunting — don’t waste it, don’t throw anything away.

I circled back to this concept later in my career, but in my early twenties I was working in chain restaurants, busy places that served burgers, fries, nachos, that sort of thing. I still didn’t know enough about food and cooking. I remember a trip that my then-girlfriend and I took to Las Vegas. I wanted to go to a “super-fancy” restaurant, so we chose to go to Picasso, the French restaurant at the Bellagio, which had just opened and was later awarded two Michelin stars. My date and I sat there eating little bits and bites. We let the waiter pick our wine selection for us because I knew nothing about wine. We had two servers to ourselves, and there was only the two of us. There was some guy just waiting to fill our water. We sat on the veranda overlooking the fountains and the water show. I was completely out of my league. I had no clue what I was eating. I had no idea how complex it was or how hard it was to make food like that. I didn’t even understand the creativity involved. I was so naive.

I kept cooking — mostly in chain restaurants — and worked my way up through professional kitchens. I became a kitchen manager. But as I approached my mid-twenties, I started to realize that staff who were younger than me, who looked up to me for leadership, knew more about food than I did. My math wasn’t the greatest and I hadn’t really been taught much because I was promoted ahead of my skill level simply because of my work ethic.

It’s an uncomfortable position to be in, when you feel you’re supposed to be at a certain level and you know you aren’t there. It was especially difficult when I was running a place and I knew the cooks were better than me. I couldn’t give them any guidance. I couldn’t help or coach them. All I could do was lie.

I decided I needed to get out of chain restaurants, where I really only learned how to follow instructions, not cook. It worried me. I didn’t want to wake up one day and not know anything about the fundamentals of cooking. So at 23 years of age I enrolled in culinary school — but I only completed the first year before a divorce and some family things meant I had to go back to work full time.

I started work at a hotel and began all over again as a garde manger, an entry-level kitchen job making salads and other basic dishes. I also did banquets. I did every kitchen job I could to get myself back on track. Only this time I decided I needed to work my way up properly.

I got to write my first menu at a restaurant called Dezio’s. I was a kitchen manager and chef there. I was also chef at a Lebanese restaurant, where I learned to make dolmades, fattoush, and shakriya, which is a hot yogurt stew. That job impressed upon me the importance of food in a larger cultural context. We’d go to the owners’ house for these huge feasts—enormous gatherings where everyone’s kissing and hugging, drinking wine, having fun, getting drunk, smoking cigars, eating a ton of food, and talking in their native language. It was like nothing I had experienced before. And it was all combined with music, art, culture, and dancing.

Finally, I returned to culinary school and graduated. In 2006, I was hired as executive sous-chef at Sage, a fine dining restaurant at the River Cree Resort & Casino, a then-new operation on the Enoch Reservation on the western edge of Edmonton. It was an expensive, Las Vegas–style steak and seafood place where you paid extra for every side on your plate. It worked because it was one of the only new restaurants to open in Edmonton that year.

After two and a half years, I left Sage to work at another restaurant, Dante’s Bistro. One night a man from the Enoch band recognized me. He asked, “What is your earliest memory?” I told him I was adopted and didn’t know where I was born or who my biological parents were. All I had was a photo of me as a toddler with two other kids. There were three names written on the back: Shane, John, and Gordon. I assumed that those were the names of the three of us in the photo.

“No, those are your names,” he explained. “I am your first cousin. You are from Enoch, and your name is Shane John Gordon. You’re from the Gordon clan.” (The “St. John,” I was told, came about later because I loved going to church when I was very little. I also learned that my biological mother, Gloria Gordon, was from Enoch, where I now work and have my own restaurant. In a strange way, I’ve come full circle in my life because of my career.) Finally, I had an anchor for my identity. I was Plains Cree from the Enoch Nation. But I still had a lot to learn and I didn’t even know where to begin.

After Dante’s Bistro, I was hired as executive chef at a restaurant called L2 in Edmonton. It was an Asian-inspired restaurant, and I started learning about a whole new category of ingredients. It was a very creative time for me. I was given very little direction from the management, and they let me and my staff experiment as much as we wanted. We’d go off to an Asian grocery store that was in the same shopping mall — okay, not just any shopping mall; it was West Edmonton Mall, the largest shopping centre in the world at the time — and buy live eels, geoduck, and whatever else we could get our hands on. Then we’d cook them up for our staff meals.

I became very interested in Susur Lee, a Canadian chef who was world famous for the Asian-fusion cuisine he served in his restaurants in Toronto. Understanding how Susur was able to incorporate his Hong Kong and Chinese cultural influences in a modern Canadian context was a light-bulb moment for me. He made me realize that there was a way for me to discover Indigenous foods and ways of cooking through my own interpretations.

One day at L2 I cooked for a delegation of 20 people from the Navajo Nation. I served a seven-course upscale menu that involved a saddle of rabbit and a higher-end version of bison tartare, along with some other dishes. I felt really great about the menu and the food — something clicked inside me. It was so exciting. And my food made them so incredibly happy that I knew I had to keep going.

I returned to Sage in 2013, this time as executive chef, and within a few years the restaurant was remodelled and rebranded as SC—for Shane Chartrand. Since the very beginning, I have found the work environment and community at the River Cree Resort & Casino to be incredibly supportive. I’ve been able to organize dinners that showcase my ideas around progressive Indigenous cuisine, and we have many Indigenous and Indigenous-inspired items that regularly rotate through the menu.

When I first began talking about progressive Indigenous food, most people were puzzled. What does that mean? How are you going to do that? How is contemporary Indigenous cooking different from mainstream Canadian cooking? How is it the same?

A lot of my cooking is mainstream—dishes that use classic European techniques and global ingredients. But the more I explore my Indigenous roots and develop my vision of progressive Indigenous cooking, the more people from all walks of life are excited about what a First Nations perspective can bring to the plate. In my culinary journey, I am trying to get to know myself better. But I also want to know more about Indigenous cultures and communities. So where do I start?

Well, I started by talking to Elders, to people from my own Nation — by sticking my nose in where it doesn’t belong and by listening. I still feel like an outsider a lot of the time and I work hard to make connections so that I gain the trust of people who can teach me what I need to know — to try to put the pieces together. Now wherever I travel, I try to connect with local Nations. I’ve become bolder about that sort of thing. I want to learn more about different cultures in the Indigenous world. I continue to think, learn, listen, and create as I hone in on what progressive Indigenous cooking means to me. How can I make First Nations food exciting? How can I write a book that you just can’t put down? As I’ve been thinking about these things, I said yes to every television appearance, speaking engagement, and event where I could learn something new or expose my ideas to a wider audience.

For instance, in 2015 I appeared on a competitive cooking show called Chopped Canada, where I dedicated my participation to my mom and dad as a big public thank-you for adopting me. Winning the competition wasn’t as important to me as inspiring Indigenous kids to do something that they might not have considered before — to go to culinary school, to be a restaurant manager, to be a chef, to be on a television show. I certainly didn’t grow up seeing faces in mainstream media that reflected how I looked and where I came from. So for me, the most important part of my presence on Chopped Canada, and any other television and documentaries I do, is representation. What keeps me going is the realization that the more I talk, the more people listen. There’s a lot of momentum. At the end of the day, it’s my contribution, my way of helping. If people are still interested, I’ll keep talking.

My thinking on progressive Indigenous cuisine has evolved since I started on this journey 10 years ago, and I imagine it will continue to expand and grow. But I feel like I finally have a good, clear idea of what feels authentic and exciting, not just to me but to more and more people who are excited by the exploration of Indigenous perspectives in food.

That said, if I was going to celebrate only Indigenous people and purely Indigenous ingredients and cooking techniques in my cookbook, it would go against everything that I am doing at my restaurant. At SC, I often use European and Asian cooking techniques. I love coriander seed. I do a lot of pickling. For me, it’s about making something new and interesting out of various influences. In other words, I didn’t want this book to be just about me and only about the First Nations side of me. Sure, it’s about my life, my recipes, what I like to cook and eat, where I like to travel. It’s about finding those information bundles that we all can share and learn from. After all, food is a place where the Indigenous and non-Indigenous worlds can easily connect. Whether you have Indigenous ancestors or not, everyone in North America should be learning about the First Nations’ cultures that surround them. For my part, I can share recipes that I’ve created or learned, relay stories, and highlight the creativity of my Indigenous world through food.

The idea is to bring the beauty and artistry of my world to everybody.

________________________________________________

The following recipes are generously excerpted from tawâw: Progressive Indigenous Cuisine, courtesy of House of Anansi Press.

YELLOWFIN TUNA WITH SEAWEED SALAD AND GLASS NOODLES

MAKES 4 SERVINGS

You may be surprised to find a Japanese-inspired dish in a contemporary Indigenous cookbook, but I’ve had a long-running fascination and love for Japanese cuisine. I go for it over French

and European food almost every time. I love the precision of Japanese food, and how clearly

it represents itself as a cooking philosophy. It proves to me over and over again that you don’t need to start with a classic French mindset or flavour base, and it inspires me when dreaming up Indigenous dishes. It also reminds me that in my lifetime Canadians of all backgrounds have come to love Japanese cooking. Someday the same will be said for Indigenous cuisine.

FOR THE SEAWEED SALAD

3 oz/85 g glass noodles (also known as cellophane noodles)

1⁄2 oz/15 g dried wakame or kombu (kelp) seaweed

3 tbsp/45 mL unseasoned rice vinegar

3 tbsp/45 mL Japanese tamari or soy sauce

1 tbsp/15 mL sesame oil

2 tsp/10 mL good-quality organic honey or granulated sugar

1⁄2 tsp/2.5 mL red pepper flakes

1tbsp/15 mL grated, peeled, fresh, ginger root

1⁄2 tsp/2.5 mL minced garlic

2 tbsp + 2 tsp/30 mL + 10 mL sesame seeds (white or black), divided

Sea salt

Juice of 1⁄2 lime

FOR THE SESAME MAYO SAUCE

3⁄4 cup/175 mL mayonnaise

2 tbsp/30 mL sesame oil

1 tbsp/15 mL hoisin sauce

1 tbsp/15 mL Sriracha sauce or Gochujang (Korean chili paste)

3 tbsp/45 mL toasted sesame seeds 1⁄2 tsp / 2.5 mL ground cumin

15 fresh chives

Salt and freshly ground black pepper

FOR THE TUNA

3 sheets green nori

Pinch of sea salt

1 yellowfin tuna loin, sliced across the grain into 12 pieces (1⁄2 inch/1 cm thick)

2 tbsp/30 mL canola oil

1 tbsp/15 mL togarashi seasoning or red pepper flakes

- Make the salad: To cook the glass noodles, place them in a large heatproof bowl and cover completely in boiling water. Cover the bowl with plastic wrap or a tight-fitting lid and set aside for 10 to 15 minutes, until tender but firm.

-

Meanwhile, place the seaweed in a large bowl with lots of cold water. Let soak for about

5 minutes, or until the leaves are very flexible. Drain well (reserve bowl) and cut the prepared seaweed into very thin strips. Return to the reserved bowl and set aside. - In a small bowl, whisk together the unseasoned rice vinegar, tamari, sesame oil, honey, red pepper flakes, grated ginger, and minced garlic. Set aside.

- Once the noodles are ready, rinse them under cold running water until completely chilled. Drain well and place them in the bowl with the seaweed. Add 2 tsp / 10 mL of the sesame seeds and the vinegar mixture. Season with a pinch of salt and a squeeze of lime. Toss well to combine. Taste and add more salt, if needed. Set aside.

- Make the sauce: In a blender, combine the mayonnaise, sesame oil, hoisin sauce, Sriracha or Gochujang, sesame seeds, cumin, chives, and salt and pepper. Blend until smooth. Set aside.

- Prepare the tuna: In a food processor, combine the nori sheets, remaining 2 tbsp/30 mL sesame seeds, and a pinch of salt. Pulse until you achieve a coarse texture, like coffee grounds. Transfer all but 2 tbsp/30 mL of the sesame-nori mixture to a shallow bowl or pie plate. Roll the tuna loin in the sesame-nori mixture to coat, pressing it firmly onto the surface. (You can also roll the coated loin in plastic wrap very tightly, give it a good squeeze, and then unwrap it.)

- In a cast-iron skillet, heat the oil over medium-high heat until it shimmers. Sear the tuna loin by just lightly touching each side to the hot pan (you are not trying to fully cook the tuna, just the top 1⁄4 inch/0.5 cm on each side). Let the seared tuna rest on a cutting board for a minute or so. Using a sharp knife, cut the tuna across the grain into twelve 1⁄2-inch/1-cm pieces.

-

8 To serve, put 1/3 cup/80 mL of the sesame cream sauce in each serving bowl. Top with about

1/3 cup/80 mL of the seaweed salad. Lay 3 pieces of tuna across the salad. Sprinkle with a pinch of togarashi seasoning and a pinch of the reserved nori sesame crumble.

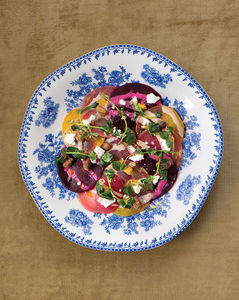

SALT-ROASTED BEET AND GOAT CHEESE SALAD WITH CANDIED PISTACHIOS

MAKES 4 SERVINGS | SPECIAL EQUIPMENT: RUBBER OR LATEX GLOVES (optional)

We often ate this salad during our marathon days in the kitchen creating and recipe testing for this book. It’s tangy, earthy, and sweet all at once. That’s why it’s so good. It takes a number of steps to prepare, but you can do some of them the day before. And if there is some leftover dressing, it’s great on green salad as well, or drizzled on any of your favourite roasted vegetables.

FOR THE ROASTED BEETS

6 cups/1.5 L coarse kosher salt

6 medium red and yellow beets, leaves and roots trimmed

FOR THE DRESSING

1⁄2 cup/125 mL balsamic vinegar 11⁄2 cups/375 mL mayonnaise

1 tsp/5 mL minced garlic

1 tbsp/15 mL Worcestershire sauce 1⁄2 cup/125 mL pure maple syrup

FOR THE CANDIED PISTACHIOS

2 cups/500 mL neutral-flavoured cooking oil (such as canola), for frying

1 cup/250 mL unsalted pistachios 3⁄4 cup/175 mL icing sugar

FOR SERVING

4 oz/115 g soft goat cheese (about 1⁄2 cup/125 mL)

- Roast the beets: Preheat the oven to 400°F/200°C (see Tip on page 122).

- Pour a 3⁄4-inch/2-cm layer of the salt into a baking dish just large enough to hold all of the beets. Place the beets root-end up on the salt bed. Cover with the remaining salt and bake for about an hour.

- Remove the pan from the oven and let cool for about 15 minutes. The salt turns into a hard crust, and the beets hold in the moisture, so be careful as there might still be steam trapped. Carefully remove the beets from the salt and brush off any excess. Peel the skin with your fingers (it should slip off; you may want to wear rubber or latex gloves to avoid staining your hands). Rinse quickly under cool running water. Slice the peeled beets on the thin setting of a mandolin, about 1/8 inch/3 mm. Transfer to a resealable container, cover, and refrigerate until ready to use.

- Make the dressing: Whisk together the balsamic vinegar, mayonnaise, garlic, Worcestershire, and maple syrup in a small bowl.

- Candy the pistachios: Fill a saucepan with 11⁄2 inches/3.5 cm of oil and heat to 300°F/150°C.

- Meanwhile, in another saucepan of boiling water, blanch the pistachios for 30 seconds. Using a fine-mesh sieve, drain the pistachios (give them a few flicks of the wrist to dry them out as they cool) and transfer to a small bowl. Add the icing sugar and toss to coat well. Fry the sugared pistachios in the hot oil for 1 minute or until golden. Using a wire-mesh scoop, transfer them to paper towel to drain and cool.

- To serve, divide the beets among 4 serving plates and arrange in an overlapping pattern. Drizzle with the dressing and garnish with crumbled goat cheese and the candied pistachios.

TIP: If you are using a conventional oven, you may need to either cook the items a little longer or increase the oven temperature by 25°F/4°C.

_____________________________________

Shane M. Chartrand of the Enoch Cree Nation, is at the forefront of the re-emergence of Indigenous cuisine in North America. Raised in Central Alberta, where he learned to respect food through raising livestock, hunting, and fishing on his family’s acreage, Chartrand relocated to Edmonton as a young man to pursue culinary training. In 2015, Chartrand was invited to participate in the prestigious international chef contingent of Cook It Raw, and has since competed on Food Network Canada’s Iron Chef Canada and Chopped Canada. Currently, Chartrand is the executive chef at the acclaimed SC Restaurant at the River Cree Resort & Casino in Enoch, Alberta, where he transforms his diverse influences and experiences into culinary art.

Born and raised in Edmonton, Alberta, Jennifer Cockrall-King is a Canadian food writer who now lives in the small community of Naramata, in British Columbia’s Okanagan Valley. She is the author of Food and the City: Urban Agriculture and the New Food Revolution and Food Artisans of the Okanagan Valley. Her writing has appeared in publications across North America, including Maclean’s, Reader’s Digest, Eighteen Bridges, Canadian Geographic, and enRoute magazine. tawâw: Progressive Indigenous Cuisine is her third book.