On Margaret Atwood and the new Canlit

It’s nine o’clock on a Sunday night and my son is asleep. This is a time reserved for me, a time when I usually don’t work or think about work, when I sometimes watch Stephen Colbert videos, or documentaries about manatees (my favourite marine animal). Sometimes I just stare at the ceiling, shut off my brain, and listen to the perfect silence. Tonight, though, I have a pile of old books, an open laptop, and a stack of messy, handwritten notes arranged in a fan on the bed around me. I’m writing an essay, urgently. The notes are a record of my angry, sad, and distracted thoughts over the last week. The books? The Journals of Susanna Moodie and Lady Oracle, the first Margaret Atwood titles I ever read. And I’m writing an essay, yet again, on the balance of power in Canlit.

I had a classic English Literature education and I was taught to always, always look to the text for answers. Whenever I feel at sea about what to write, I go back to the words, to the books that set fire to my imagination when I was a teenager. For me, for many of us, those were the words of Margaret Atwood. My older sisters, who were in university when I was a teenager, often left their textbooks in our dining room bookcase. There were geophysics books that weighed more than I did, a battered copy of Our Bodies, Ourselves, four different editions of the Norton anthology. And, of course, books by Robertson Davies, Alice Munro, Margaret Laurence, and Margaret Atwood. At 14, I began making my way through these books (in all honesty, I probably spent more time on the line drawings in Our Bodies, Ourselves than anything else) and, when I read Lady Oracle, the world, or at least my world, changed.

Lady Oracle was published in 1976 and I read it in 1990. And yet, it felt contemporary, the sort of book that sounded like the way my friends and I might talk, if we were a little bit older and less self-conscious. It’s social satire, it’s feminism, and it reveals the hypocrisies of what we might call the cultural elite. I thought to myself, Maybe I can write like that one day. And maybe I will meet Margaret Atwood and tell her how much this book changed my life.

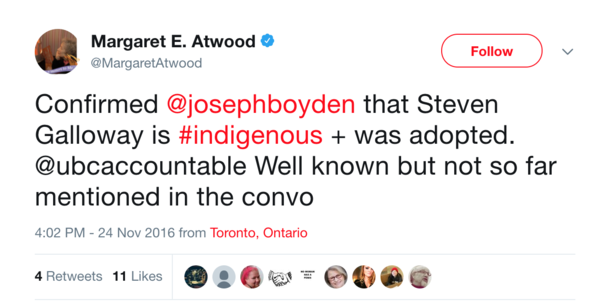

In March of 2017, I did meet Margaret Atwood, at a charity event where we, along with another author, were participating in a reading and panel to help raise funds for literacy. I was happy to be invited but I had almost refused to attend. This was, of course, during the high point of the UBC Accountable conflict, when Margaret Atwood wrote a series of tweets that were difficult to reconcile with the author whose words I had returned to again and again, ever since I was teenager. Of course, in the twenty-seven years since my adolescence, I had learned some things about privilege, about the great discomfort I had often felt whenever I was the only person of colour in a literary room, about the kinds of criticisms my books, my race, and my appearance were subject to by critics, the media, and, sometimes, other authors. I had almost cancelled this appearance to avoid any potential confrontations about UBC Accountable. In the end, though, I knew I had a job to do, and that it wouldn’t serve me or any other writer to back away. No, I thought, I’m going to take this space that has been given to me.

Many things happened during that event, including Margaret Atwood rapping some rhymes from her most recent novel. I remember her sitting in the front row while I was speaking, and her face beaming at me. She laughed at all my jokes. She nodded in agreement when I talked about my commitment to writing about the women who are at risk in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. Afterward, she bought my book and asked me to sign it. I have no memory of what I wrote in her copy, but as I handed it back, I blurted out, “I read Lady Oracle when I was 14. It changed my life.” She chuckled and said, “No one ever talks about that book. You’re very interesting.”

That night, in my hotel room, I didn’t know what to think. I had spent months worried over UBC Accountable, over how my outspokenness would impact my career. Margaret Atwood had been lovely to me. But she had also talked down to and scolded some of my dearest friends. She had made statements that made it very clear that power, and specifically, her power, was something she was willing to use to silence young women who had very little power at all. And this past weekend, in an essay for The Globe and Mail, she did it again. I don’t need to take apart her arguments, as many other writers, particularly Alicia Elliott, Michael V. Smith, and Amanda Leduc, already have, very effectively, on Twitter. What I am left with is a confusion of feelings, for the Margaret Atwood I read as a younger woman, for the Margaret Atwood I met in March, for the Margaret Atwood who seems unwilling to understand that her words, and the words of so many others, have hurt writers just like me. Because not only am I an author, I am a teacher, an editor, and a survivor of sexual assault.

Of course, this past week has also seen some other displays of privilege and power, especially from Jonathan Kay and Angie Abdou in Quillette, about how the criticism of Angie’s recent novel, which prominently features Ktunaxa characters, has inspired them both to declare that “Canada’s gone mad.” Jonathan Kay describes Angie as a “fresh-scrubbed Ivory Girl mom,” while calling her Indigenous critics “armies of Twitter trolls” and a “censorship cult.” I think we know what Jonathan means here, and it’s not pretty.

The division in Canlit has never been clearer. There are those who have benefited greatly from the old inequities in Canadian publishing and seem terrified that those benefits are waning, and who cling to a concept of writerly freedom that disintegrates when they are forced to consider the writing of the critics who engage with their work with a political eye. There are those, like me, who think this change in our industry is a good one, who think that it’s exciting to read new stories from communities we haven’t heard from yet, who believe that crafting our characters with care and a sense of responsibility makes for better writing, who mentor emerging writers and always prioritize their safety so they can create and explore. There is no question that Canlit is changing. Power is becoming horizontal, and the many voices who are dissenting, asserting, and writing, are chipping away at unearned privilege, and producing extraordinary books that people want to read. This might be scary for some. But this is what keeps me, and so many others, going.

I know what I believe. I know how my writing, editing, teaching, and social responsibilities work together. I know how to amplify the voices of writers who write good books. What I don’t know, even now, is how to love the books Margaret Atwood wrote while simultaneously feeling this much pain.

If in doubt, always, always look to the text.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

In The Journals of Susanna Moodie, in a poem titled, “First Neighbours,” Margaret Atwood writes,

The forest can still trick me:

one afternoon while I was drawing

birds, a malignant face

flickered over my shoulder:

the branches quivered.

Resolve: to be both tentative and hard to startle.

These old words—the ones I turned to when I was lovesick at 19 and again when I was 30 and needed to write a poem but couldn’t think of anything to write about—are the closest things to an answer I can come up with.

The new Canlit is now making its own resolutions. And guess what? We will not be easily startled. At least, Margaret, we have this to thank you for.

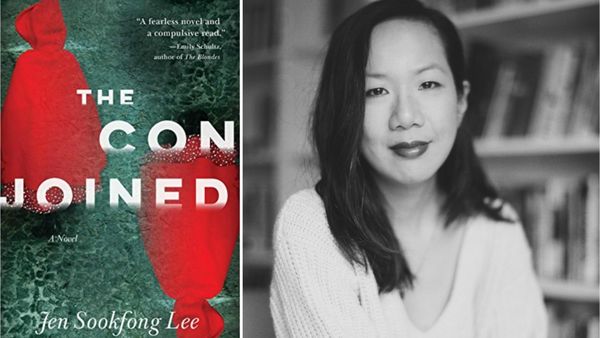

Jen Sookfong Lee was born and raised in Vancouver’s East Side, and she now lives with her son in North Burnaby. Her books include The Conjoined, nominated for International Dublin Literary Award and a finalist for the Ethel Wilson Fiction Prize, The Better Mother, a finalist for the City of Vancouver Book Award, The End of East, The Shadow List, and Finding Home. Jen acquires and edits for ECW Press and co-hosts the literary podcast, Can’t Lit.