The Essential Energy of Solitude: Jack Davis in Conversation with Pedlar Press' Beth Follett

Poets famously embrace a degree of alone time, but Jack Davis puts most to shame: he's spent the last ten summers manning a remote fire lookout in the woods of the northernmost Alberta wilds.

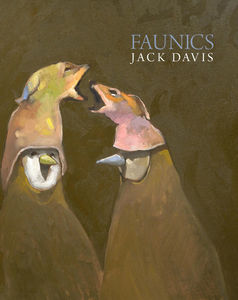

His debut collection, Faunics (Pedlar Press), captures the wilderness that inspired Davis. Animals were his company as he worked for over a decade refining the poems (even his Twitter handle echoes his love for his animal friends: ReadingAnimal). The isolation and focus of his experience brought about a kind of "pure attention," as Davis puts it.

Pedlar Press publisher Beth Follett interviewed Davis on behalf of Open Book. We're pleased to present the full interview here, where Davis tells Follett about why he's chosen the degree of isolation he has and how it impacts his writing life, the importance of Maggie the snoring bear to Faunics development, and much more.

Our thanks to Beth Follett for sharing this interview with us.

Beth Follett for Open Book:

You are about as far as a poet can get from confessional. Can you talk about which literary tradition you, and your collection Faunics, belong to?

Jack Davis:

Without listing the books piled on and around my desk as I wrote these poems — which I would love to do — I would hazard to locate Faunics, poetically, somewhere between two Parises: Paul Celan’s and Nelson Ball’s. Both poets are dedicated to a form of pure attention; one through the transparency of a painstakingly plain language and the other by reaching for some pre-linguistic current that flows underneath language itself. Both modes and methods are the inheritance of my years of reading and writing, which are inseparable activities in my experience, and run through this collection.

There’s a wonderful line from American poet, Pam Rehm, that commends: “You have hidden yourself well / in attention.” For me this is aspirational, but it’s also an apt address to many of the poets whose work I admire and respond to in my own writing. For me it implies a form of attention to the world that seeks to make the writing and speaker of the poems not invisible or vatic or from some feigned objective voice, but transparent, like a window, through which the light of what’s outside enters into the room we call home. The room of the mind, which is not without its own lamps that cast light back on the world and its reflections.

This way of writing is, ultimately, also a form of introspection, or self-interrogation, too, but stops shy of confession. "The eye, not the I," as Joanne Page put it.

Not all the poets that interest or have influenced me work in this kind of transparent voice, but they often share a tendency toward compression, concision and a focused observation, either direct or peripheral, as a meditative and philosophical mode. I’m attracted to work that that operates this way—in which revelation is a subtractive process. That is the tradition Faunics belongs to.

BF:

John Berryman once said he masquerades as a writer, that really he is a scholar. Do you have a hidden identity behind Poet? Or perhaps Poet has been your hiddenness behind Watchtower Sentinel?

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

JD:

“Poet” has most definitely been my hiddenness; behind whatever I happen to be doing or whomever I happen to be speaking to at any time. Writing has been a private and personal activity and not something I’ve shared or discussed for most of my twenty years of writing life, aside from the occasional handmade pamphlet given to a few friends once a decade. The inevitable revealing of this hidden vocation has been an interesting aspect of the publishing process for this first collection and one that, strangely, I had not considered beforehand. Even answering these question here, talking to you, involves articulating things I’ve not asked of myself until now. I shift between optimism and my more native trepidation about what this new experience will mean for my writing life. I’m interested to find out. I will report back.

Perhaps I’m a writer masquerading as a petter of dogs and talker-to of squirrels and birds. Or vice versa. Or maybe I’m all these things, masquerading as an evader of direct questions.

BF:

I’ll try to be more direct! Do you write in summers when you are at work at the fire tower in northern Alberta? How does the fire tower feature in your poetry?

JD:

I’ve been fortunate to find paying work that provides the conditions that I’ve sought to achieve, with varying success, throughout my adult life: time, quiet, solitude, and a reliable daily repetition of the same. This rhythm is important for me to accomplish any writing—to be able to continue the long, uninterrupted conversation with myself until it sprouts into words that want writing. Like following a thread through the woods and back home. The nature of the fire lookout work is rich in such unbroken time. Even in a busy area for forest fires like the one I’ve worked in, the hours and days spent looking are only rarely interrupted by the appearance of an actual fire.

The tower itself is a vantage point, a crow’s nest from which I can see the changeable sea of trees that are my responsibility and can observe the various wild animals whose corner of forest I share. I have bears that return year after year, doing the rounds of their individual territories, and I can identify some of them now by their physical distinctions and personalities. Maggie the bear was a regular visitor for several summers, but I haven’t seen her in a couple of years. I spent many evenings eating dinner at the makeshift desk on my cabin porch below the tower, as Maggie snored in the bindweed and dandelions a few metres away from me. I’ve missed her company.

BF:

Why have you chosen to spend so much of your adult time alone in nature?

JD:

For the time, quiet, and rhythm of the life it affords me. An introvert by nature, being alone is easy and natural for me and I find solitude energizing, although I usually have at least one dog or several roaming bears or a visiting fox or a resident groundhog for company, too, so I’m not actually alone.

For me, nature is the model, the aspiration of thought and its form. Its boundless dynamism, its inexhaustible interconnections, diversions, mysteries and disclosures are endlessly fascinating and inspiring to me. The experience of living with a natural, wild place and trying to be a part of it, not as a setting for my own stories and plans, but as another organism inside its ecosystem, is rewarding in a way it's hard for me to imagine tiring of. I share George Oppen’s “…pure joy / Of the mineral fact” of the natural world, its presence, and the daily renewed amazement at the “because they are there’-ness,” of its numberless forms of ingenious life, which persist around, alongside and despite our own. This is what fuels my fire and I’ve been fortunate to make a life with no shortage of fuel.

BF:

You take an annual canoe trip in August. How long have you done so? Is it always the same route? Do you always go alone? Do you pack books to carry with you?

JD:

I go with a group of old friends, always the same ones, and we’ve gone every year for almost thirty years now. The route has varied over the years, and shortened with age and responsibilities, but it is still a reliable piece of time-travel from whatever lives each of us leaves to do the trip together. The last couple of years we paddled through Killarney Provincial Park, which is one of my favourite places. This year we travelled a few of the many beautiful channels of the French River leading down to Georgian Bay. It’s not a ‘bookish’ excursion by any means, but I’ve lately taken to bringing a book along for the day of fishing that has crept into the itinerary, to which I am a conscientious objector. This year I brought Journeys Through Bookland, by my friend and editor, Stan Dragland, and relived it the shade of wind-bent white pine.

BF:

I swear I was innocent of that fact when I posed the question: not a plug for the darling Dragland.

What is the nature of your dreams?

JD:

For someone cursed with chronically poor and fragmentary sleep, I very rarely remember my dreams and when I do they tend to be tediously mundane—symptoms either of a disappointingly dull subconscious or a reluctantly protracted waking life that is efficient at digesting its shadows and feral edges.

When I was young I often dreamt of rabbits. The last dream I remembered was a week ago. In it, a small, (hopefully) sleeping pile of white baby rabbits was ‘produced’ from the mouths of one of our dogs, there between my feet as I spoke to some faceless person who pretended not to notice. Out of politeness, I imagine. All these rabbits remain unanalyzed.

Place, for me, is an important part of my writing process and I’m interested in where and how writers write. I’ve often thought that I’d rather see a photo of a writer’s desk at the end of a book than their portrait. It would tell me more about where the book came from. I knew you as a writer many years before I ever imagined I’d know you as a publisher and editor, and with your impending retirement from those roles for Pedlar, I’m hoping, along with many others, that this will mean there’ll be new writing from you to look forward to. How and where does writing get done for you?

BF:

Pedlar has kept me hopping for most of twenty-one years, and hasn’t afforded me the kind of thinking time I need to finish a novel I began in 2004. That said, I have produced a few works that have gone public. To write I have to insist on dating the writer in me, and on keeping my dates with her. I am terrifically interested in the ‘spaces like stairs’ beyond the surface of the mind, beyond mind’s cravings and aversions, interested in how these get articulated in language and the body. I have practices I perform in silence. This might be a stretch for many people, but I am writing when I meditate and when I practice yoga, which I do almost daily. However, only empty paper to show.

Thank you so much, Jack.

______________________________________________

Jack Davis was born in northern Ontario and lives in Parry Sound. For the past ten summers he has lived and worked at a remote fire lookout in the woods of northernmost northern Alberta. He is a friend to animals. Faunics is his first book.