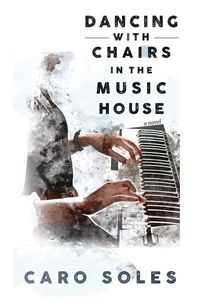

Travel Back to Toronto in 1949 with an Excerpt from Caro Soles' Dancing with Chairs in the Music House

In Caro Soles's Dancing with Chairs in the Music House (Inanna Publications), a family's life in late 1940s Toronto takes a tragic turn. Ten-year-old Vanessa lives in a rooming house on Jarvis Street and suffers from a condition that means she could lose her sight. To keep her safe, her parents keep her home and have her tutored by a cast of colourful characters. In her free time, she roams the house and gets to know its strange inhabitants, gathering secrets.

Vanessa is plucky and as adventurous as her confined circumstances allow her to be, so when the opportunity arises to help one of the residents with a seemingly innocent task - delivering a mysterious note to a friend at church - she jumps at the chance. Little does she know that innocuous favour will unleash a wave of destruction.

Soles' tightly woven historical tale has earned praise for its haunting, evocative atmosphere and its rich rendering of the era. With endorsements from the likes of Linwood Barclay and Murdock creator Maureen Jennings, it's a perfect read for anyone interested in travelling back to a Toronto of the past with an unforgettable narrator.

We're excited to share an excerpt from Dancing with Chairs in the Music House, courtesy of Inanna Publications.

Excerpt from Dancing with Chairs in the Music House by Caro Soles:

I run down the stairs, across the quickly melting snowy lumps of our yard, and into the corner. I push behind the lilac bush and find our log undisturbed. Janet and I have wedged it against the fence to give us a step up. It’s harder to climb the fence on my own, but I finally pull myself upright and stand on the narrow wooden beam that runs along the top, holding on to the bush for balance. I look down and it seems a long way to the ground. I look up quickly. When Janet’s here, we usually put one foot on the corner post and take a big step over the yawning chasm below onto the garage roof. But today, for the first time, I look to my left and realize the coach house building is very close. I can almost see into one of the windows on the ground floor. The glass is dirty, the putty falling out from between the panes. Faded yellow paint peels off the wooden frames. If I lean closer, I can touch the beam of wood that runs across from the fence to the building as support. I guess there used to be a gate below it, but that’s gone now, and a sheet of metal blocks the way in from the ground.

I take a deep breath and start to edge across the beam. With every step, I can see more of the window below me. But what catches my interest now is the wide ledge above it. From there it would be easy to climb onto the roof. What an adventure that would be to tell Janet! What a great view I would have! I could see what lies behind the coach house and the garage and everything that has been hidden up to now. My secret kingdom would be huge! I imagine lying in bed, running through all the new pictures in my head. “The curtain may fall any time,” the doctor said. And Mother says, “Fill your head with wonderful images.” So we go to art galleries and museums. “Remember everything,” she says. I will remember this.

I am across the chasm now, both hands resting on the soft yellow bricks around the window frame. If I bend down, I can see inside, but it’s so dark and dusty in there I can’t make out anything clearly—just long tables and piles of junk on the floor. Someone said this place used be an artist’s studio—after the horses and coaches left, of course. Maybe there are stacks of canvases against the wall, undiscovered masterpieces, but I can’t make out anything clearly.

Climbing up on top of the window isn’t easy. I scrape my right knee badly, and for a minute I feel dizzy, thinking of my blood smeared on the rough wall. But at last I make it. I am standing with both feet on the wide lintel, flattened against the bricks, higher than I have been before, but still not on the roof, which I can now see: a lumpy expanse of tar and pebbles just above my head. I look down. It is a big mistake. My knees begin to wobble, my legs shake. My fingers dig into the rough uneven brick as panic sweeps over me. No one is around. No one will hear me if I fall. No one will come. Below me, the broken concrete of the walkway will crack my skull, tear my flesh. I think of Horatius at the bridge in the brave days of yore, of the Spartan youth letting the fox gnaw at his entrails, of Daddy and his men going over the top at Ypres into the deadly cloud of gas. This is nothing.

Gradually I force myself to loosen the grip of my right hand and reach for the rain spout. This high up, it curves into the building from the eaves above, and I am counting on it to get me the rest of the way. If I move my left foot to the brick that sticks out a few feet up, I can use the crook in the spout as support. Don’t think. Do it! “Hold that bridge,” I mutter. With my left foot up, my right foot swings into place. I heave my weight onto the right foot and push. There is a creak—a tearing, rending sound—and the pipe begins to tremble under me. I clutch the edge of the roof and scream, pulling myself desperately forward onto the pebbled tar. The drain pipe crashes to the broken concrete below. I pull one knee onto the roof and slowly haul myself up the rest of the way.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

Relief floods through me, so sharp and sudden I start to cry.

Thank you, God!

After a few moments, I calm down and look around. I am higher than Mount Olympus. I can see part of the garden behind the stables, neglected and overgrown—not a garden at all but more like a place to dump old unwanted things. Broken dishes litter the ground under the window as if someone has thrown them there, one by one, in a rage. Rusted bedsprings lean at an angle across one corner, and vines are beginning to climb through the trellis of fractured metal, disguising the ugliness. By midsummer, the view from here might be quite different. I wonder if anyone will even be able to see these broken, useless things.

When I stand up, the branches of an old elm tree almost touch my head. From this angle, the lilac bush in the corner of my garden blocks the view of the Music House, but if I move over, closer to the emerald green of the stables’ yard, I can see it all. But there are few windows facing this way, only our own from the Everything Room and the small leaded panes from up high over the built-in cupboards in our living room. There is a dormer window on the third floor, which I guess must be Mrs. Dunn’s, but the other windows are hidden by the wild growth of the bushes protecting Rona Layne’s secret garden. No one can see me.I smile in satisfaction.

The clouds are so close now that they are tangled in the trees. I bend my head back and stare up through the shifting pattern of greenery into the pewter sky. I shiver. For the first time, I realize it is getting colder. And there is rain in the air. My right leg twinges, as if the realization has reminded it to start hurting. It’s time to go home.

I take one last look around my secret kingdom and walk over to the edge of the roof where the gutters are broken. I will have to find a new way down since the drain pipe is no longer there. I make a circuit of the roof, looking for another drain pipe, crawling under the low hanging branches of the elm, but there isn’t one. The eaves are rotted away in several places, but how will that do me any good?

I crouch on the edge, looking down on the surface of Mount Olympus. It’s not that far down, but there’s a walkway between the stables and the nearest garage. I try to calculate how far away it is, if I could make it by taking a running leap. But what if I miscalculate? Or slip on the takeoff?

The first drizzle of rain streaks my glasses. Panic flutters. I can’t risk the Great Leap now. Everything is blurred. My secret kingdom suddenly changes into a prison. I am a cursed maiden doomed to spend the rest of my days on an invisible island. My right leg is beginning to hurt; I can feel the slow twist of pain that often comes in the dampness and cold. But I won’t give up.

I button up my sweater and lie on my stomach on the roof, reaching down over the edge with my right hand, feeling around for something to grab onto: a foothold, a stout vine, anything! Nothing. Tears spill out, making it even harder to see. I wonder if Horatius was cold and wet when he was holding the bridge. My knee is bleeding now, and as I sit up, I realize with horror that Mother’s bracelet is no longer on my arm.

”No!”

Panic claws at my stomach, and for a moment I think I may throw up. I look around me on the roof. Take off my glasses and dry them on my shirt. But they are wet again almost at once. I crawl around the whole roof, looking for the bracelet, running my hands over every inch of the rough pebbly surface. I pray to Saint Anthony. Janet told me about him, how he helps people who have lost things, even if you’re not Catholic. I often pray to him now, but never so fervently as today. My hands are getting numb. I blow on them and keep crawling. Nothing.

And then I know. The bracelet isn’t on the roof. It’s somewhere on the broken concrete down below. It must have slid off my wrist as I was feeling around for a way down. I can’t stop the tears, and now I am completely blind. I hug my knees and let myself cry. It doesn’t matter anyway. No one can see. No one will find me.

I hear Mother’s voice in my head: “Never give up, ’tis the secret of glory!” I wipe my nose and get to my feet. I look through the cloud of drizzle at the Music House. Jonathan won’t be home for ages. Neither will Mother. Daddy always sleeps for a few hours, and he was extra tired today after our walk. I wonder if Mrs. O’Malley is home. I shudder at having to call her for help, but I don’t see any sign of her anyway. In case someone might glance out their window, I wave my arms above my head and jump up and down. But who would be looking? Why? And how could they see in all this grey dullness? I sit down again and huddle in misery.

“Vanessa?”

I freeze, afraid to look.

“It’s me. Brian.”

I wipe my eyes and swivel around on my bottom. Brian’s head and shoulders appear at eye level, through the mist. Tiny droplets of water glisten on his blond curls.

“It’s all right,” he says, holding out his arms. “I’ll help you down.”

I can’t speak. My teeth are chattering with nerves. Cold. Fear.

“Come on.” His arms are reaching out to me.

Count Brian. My knight in shining armor.

I crawl over to him and slide into his arms, and he lifts me to the top of the fence, holding me steady till I get my balance and climb down the way I usually do.

“Thank you.”

He smiles and brushes off his trousers.

I tell him about Mother’s bracelet, and he jumps over the fence as if it was nothing, finds it among the cracked concrete, and climbs back again. I thank Saint Anthony silently, then Brian out loud. Twice.

“I was on the roof getting some air,” he says, and I know he means smoking. We’re walking up the stairs to the porch. He’s holding my hand. “I saw you climbing. That was pretty brave. Bad luck the drain broke. I went inside for a while and didn’t realize you couldn’t get back down until I saw you jumping up and down, waving your SOS.”

I hiccup. “I wasn’t supposed to be up there.”

“I figured as much,” he said. “I wasn’t supposed to be entertaining a friend either. Or smoking, for that matter, so we’re both guilty. It’ll be our secret. Deal?” He held out his hand.

I nodded. “Deal.” It sounds very grown up. I’ve never said that before.

“No one will ever know,” he whispers. “Cross my heart and hope to die.”

I shiver as I watch him run down the hall backwards, a finger to his lips. Then he turns and disappears through the archway to the third-floor stairs. “I’ll never tell. Never,” I say to myself. Then I go into the Everything Room to put the bracelet back where it belongs. Brian and I share a secret. I feel warm inside in spite of the rain.

___________________________________________________________

This excerpt is taken from Dancing with Chairs in the Music House by Caro Soles, copyright © 2020 by Caro Soles. Published by Inanna Publications. Reprinted with permission.

Caro Soles’s novels include mysteries, erotica, gay lit, science fiction, and the occasional bit of dark fantasy. She received the Derrick Murdoch Award from the Crime Writers of Canada, and has been short-listed for the Lambda Literary Award, the Aurora Award, and the Stoker Award. Caro lives in Toronto, loves dachshunds, books, opera and ballet, not necessarily in that order. Visit her online here.