Words & Pictures Interview with Sasha Suda, Assistant Curator, AGO

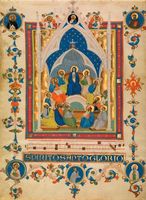

We may worship our bookshelves in our own ways today, but early books had a much more literal connection to the spiritual. They were considered art objects and closely bound to religious tradition — it's no coincidence that Gutenberg's first project in movable type was a Bible. After book production moved out of monasteries, guilds of highly skilled scribes and illuminators worked on books, many of which were subsequently stolen, sold, hidden and cherished through the centuries before finding homes in our art galleries and museums.

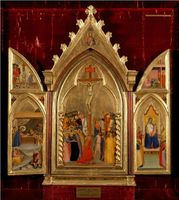

This month the Art Gallery of Ontario is celebrating and delving into that aspect of the history of the book with their lecture series Disbound and Dispersed, which serves to explain and enrich the exhibit Revealing the Renaissance: Art in Early Florence, which is on display at the AGO from March 16 to June 16, 2013.

Assistant Curator of European Art Sasha Suda is the mind behind this initiative. Her first, sold out, lecture on the subject proved so popular that a second date was added, which also sold out.

Sasha is an expert on the living history of books, a story which incorporates religion, technology, visual art, politics and almost every other aspect of human history.

Today we speak with Sasha about Disbound and Dispersed, her own career path and how ancient books continue to fascinate us today.

Be sure to click and check out the beautiful illuminations accompanying this story, which have been loaned to the AGO from museums and galleries around the world in a unique and unprecedented collaboration. Our thanks to the AGO for the use of these images.

Open Book:

Tell us about Disbound and Dispersed.

Sasha Suda:

Any work of art lives varied lives throughout its history — first it functions the role its maker and patron define and then it changes hands and lives to the expectations of its next owner. Sometimes, its physical nature changes to meet those expectations and so its trajectory changes again and again. Manuscripts and altarpieces are perfect objects for this — they are comprised of many panels, or pages, that start with comprehensive meaning and function (you need all the pages or panels for the work to serve its audience), but with time that function might fall away (it leaves a church and enters someone’s home as “art”) and so its no big deal to saw the altarpiece apart or to cut the pages out of a book. This lecture is about the motivations for taking things apart and about wrapping our heads around the fact that sometimes the unthinkable — cutting a book apart — revitalizes an object and brings it back to life.

OB:

What was the genesis of the discussion event? What are you hoping guests will take away from the evening?

SS:

I hoped to shed light on works of art that are sometimes hard to understand as objects and I hope that guests look closely at manuscript leaves when they encounter them in art museums here and elsewhere. Also, I want people to think about the choices that are made throughout an object’s lifespan that decide its fate and survival.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

OB:

Tell us a little about your career path and how you came to your position at the AGO. Were you always planning on returning to Canada?

SS:

I studied art history at Princeton University (AB), Williams College (MA)), the Institute of Fine Arts (Ph.D., in process) and worked at great museums in the US — the Clark Collection and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. I had no idea that I would study art history when I left and I had even less of a clue that it would bring me back to Canada — when you study medieval art you don’t generally get to choose where you end up. I would say that the lynchpin opportunity for me in my career was the undergraduate summer internship at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2003. It opened my eyes to so many fascinating questions around how and why museums worked.

OB:

What does an average work day look like for you?

SS:

The best thing about being a curator is that I might have a day full of meetings, or I could be offsite looking at someone’s private collection in Toronto. Sometimes, I travel with works of art that go on loan to other institutions for temporary exhibitions and other days I might spend the whole day in the library doing research. My favorite place to be is in the AGO galleries working on the permanent installation enhancing lighting or just taking in the art like any other member of the audience.

OB:

Why do you think it is that illuminated manuscripts continue to interest people? And what draws you to them personally?

SS:

Books have always been a central aspect of our culture — even with kindles and iPhones, people love looking at them! I’m not sure what it is, their tactility perhaps? That’s definitely what drew me to them — as a manuscript scholar I get to turn the same pages that were turned by viewers over 700 years ago, its an incredible feeling bridging past and present that way.

OB:

What sort of art do you have in your own home?

SS:

My husband Albert and I have a lot of art given to us by our friends — it varies and all has very personal meaning to us. We were given a single manuscript leaf for our wedding by a family friend… it's so sweet and rarely noticed by visitors to our home. It’s our little secret.

OB:

What do you feel the AGO's role is in the city, and how does what you do fit into that role?

SS:

The AGO is here to invite Torontonians and visitors from beyond the GTA boundaries to experience art in new ways and to ponder the limitless potential of human creativity.

OB:

What's next for you?

SS:

My next project will explore how miniature boxwood sculpture was made in the early 1500s – same as my answer to question #8 would be.

Check this out.

We are turning the initiative into a major exhibition with both an American and European venue!

Sasha Suda is the Art Gallery of Ontario's Assistant Curator of European Art. Specializing in Medieval Art, Suda returned to Toronto from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in early 2011. She is a Toronto native who graduated from Princeton University and served as an Andrew Mellon Research Fellow in the Department of Medieval Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. She is currently completing her Ph.D. dissertation on images of martyrdom and mutilation in medieval Christian manuscripts.

Discover the art that changed the world — Revealing the Early Renaissance: Stories and Secrets in Florentine Art — on now at the Art Gallery of Ontario until June 16.