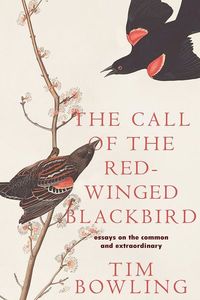

Wrap Up 2021 with an Excerpt from Tim Bowling's Meditative Book of Essays, The Call of the Red-Winged Blackbird

For our final post of 2021, we're sharing an excerpt from a truly special book. Tim Bowling, the award winning author of more than twenty books of poetry, fiction, and nonfiction, draws on sixty years of life, love, and writing in The Call of the Red-Winged Blackbird: Essays on the Common and Extraordinary (Wolsak & Wynn).

Meditative, lush, and thoughtful, the essays draw out the joy of simple pleasures in the wake of life's complexities. Engaging with beauty, money, art, and identity in an increasingly frenetic world, The Call of the Red-Winged Blackbird is a call for embracing the gentle joys we can, where we can, in particular those of the natural world.

The title is taken from a tradition Bowling's mother created, where she imitated the titular bird's call in order to call him in from playing in the evening, signalling a focus on simple, outdoor freedoms and pleasure and their power to let us see ourselves more clearly.

The contemplative and wise tone of these essays is a great way to start off a New Year, and to give yourself space to reflect in anxious times. We're proud to end our year at Open Book with this excerpt, courtesy of Wolsak & Wynn, in which Bowling takes us to an appropriately wintery Edmonton, where he finds beauty and inspiration in the frozen, empty city, riffing on everything from famous hermits to Dostoyevsky.

Excerpt from The Call of the Red-Winged Blackbird by Tim Bowling:

Deep winter in Edmonton, the most northerly city in North America with a population of over a million people, can be forbidding, desolate, and long. Temperatures with wind chill often dip below -40 Celsius, and snowfall has been known to start in September and last until May (and, on rare occasions, even June). But the deep winter can also be beautiful, especially for someone seeking solitude. To go outside on a severely cold night at the start of a New Year is to celebrate absence: absence of sound, absence of people, sometimes even absence of feeling in your extremities.

I left the house an hour after midnight, with no particular destination in mind. I merely wanted to experience the stillness that comes with such extreme cold. Immediately, I felt the sharpness of the wind on my face and watched a cloud of my own breath flow behind me like thrown water. Within minutes, I had tears in my eyes and had to remove my glasses so I could dab away the moisture and clear my sight. As soon as I put my glasses back on, I became aware of two things: the apocalyptic emptiness of the neighbourhood, and the startling size of the full moon. Somehow the two things seemed related, as if the moon had transferred its barren landscape to the earth. The recent and still fresh snow, several feet deep on the lawns and rooftops of my neighbours’ properties, only added to the illusion. Uneasily, I kept my eyes on the moon as I seemed to walk across its surface.

The only sound I heard – of my boots crunching the thin layer of snow that the ploughs had left behind on the street – was alarmingly loud. I looked down at the grey-black striations on the pavement, half-convinced that I was crushing clam shells with each step. But eventually I grew used to the sound and returned my attention to the moon.

It was much larger and brighter than normal, what is known as a Super moon, a full moon at its closest orbit around the Earth. Its size, in fact, stopped my progress, almost seemed to call out to me. After all, what is more solitary than the moon? The sun, perhaps, though its heat detracts from the association of loneliness. Also our own planet. As Walter de la Mare says of the Earth in Desert Islands and Robinson Crusoe, “Is not this great globe itself a celestial solitary?” From that question, it seems only logical to ruminate on our own solitude, as de la Mare does thusly, “flesh is flesh and bone is bone, and only by insight and by divination can we pierce inward to the citadel of the mind and soul.”

Such is our fate on our familiar great globe. In any case, where celestial bodies are concerned, the sun cannot be walked on, and the earth has been trod by billions. As for the moon, its paradoxical proximity and distance, its history since the summer of 1969 and the Apollo 11 mission, deepens its solitude. We have touched its surface, but we have lost interest in the achievement; we have lived most of our species’ existence relying on its light, but now we rarely notice the illumination; we once saw the moon as a glorious dream, but now we require a second habitable planet to satisfy our imaginations and, perhaps, to preserve our kind

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

Yet there shone the moon in the southern sky, one dim star to its left, a vague constellation to its lower right, and the craters across its middle like partially-healed black eyes. I felt sorry for it; the moon, despite its undeniable majesty, seemed abandoned. The more I stared at it, the more I began to feel sorry for myself, to doubt the wisdom of my growing hunger for solitude. The cold around me suddenly became the cold of space.

I tried to shake off the feeling, to focus on my surroundings. The branches of the great elms along our street seemed brittle as icicles; even the chimney smoke blown sideways by the wind looked as if it could snap in two. Suddenly a terrific echoing sound, as if the tectonic plates of the darkness had shifted, broke the silence. I recognized the sound after several seconds. It was the shunting of boxcars in the railyards several miles away.

I walked on. After ten minutes, I had seen no people, nor even heard a car or a siren, though I live close to the city centre, to two major traffic arteries. Just as unsettling, I encountered no animals – no scavenging coyote, no jack rabbit moving like an Alice in Wonderland chess piece into and out of a street lamp’s glow. The cold closed around me, but only my feet felt numb, even through my Blundstones and two pairs of wool socks.

Again, the sound of my walking and the numb heaviness of my step turned me back to the moon. I almost felt guilty for trying to ignore it. But I couldn’t for long. How could I? A fisherman’s son, and later a fisherman myself, I knew intimately the friendship of that lunar light, knew the security and comfort it gave on a dark and fast-running river. More than that, I was a child of the Space Age, five years old and on the Fraser River with my father that July day when Neil Armstrong took his famous small step and giant leap.

How strange it was to think that the bootprints of Armstrong and of the eleven other humans who walked on the moon after him still marked its surface. Because there is no atmosphere on the moon, no wind and rain, no erosive action, the bootprints of the astronauts will never disappear. I looked down and behind me. Even just seconds after I had stopped, all signs of my progress were so faint as to be invisible; I left no discernible impression on the frozen street. Looking back at the moon, I tried to recall what I knew of its surface. Wasn’t it colder there than on the earth? Permanently cold? Or wouldn’t it be like the earth, warm or cold depending on its relationship to the sun? How could there be any bootprints at all if the surface was frozen-solid rock?

I realized then that what I knew of the moon was the stuff of mythology not fact, including my fisherman’s belief that a ring around the moon meant that the salmon would be on the move. Then I understood, with a shiver of intuition, that I really knew nothing substantial about human nature either, perhaps least of all my own. Dostoyevsky, in his classic short work of alienation, Notes from Underground, addresses this point directly:

In every man’s memory there are things he won’t reveal to others, except, perhaps, to friends. And there are things he won’t reveal even to friends, only, perhaps, to himself, and then, too, in secret. And finally, there are things he is afraid to reveal even to himself, and every decent man has quite an accumulation of them. In fact, the more decent the man, the more of them he has stored up.

The moon I could learn about through books, but human nature, especially in regards to the relationship between solitude and community? Only partially so, because each person’s experience of this dynamic must be more individual than it is universal. Was it likely, for instance, that I would ever feel the way about my fellow beings and life itself that Montaigne felt, or Thoreau, or Dostoyevsky? What about Christopher Knight, my contemporary, who walked into the Maine woods the same year that I left university and vanished into the dying culture of the west coast salmon fishery? (according to Finkel, Knight’s favourite book is Notes from Underground). What he carried into those woods – experiences, memories, tastes – was certainly different from what I carried at twenty two, and what I carried then perhaps has only a small relation to what I am carrying now. We aren’t one person through time, no matter how much we focus on and celebrate the self.

I had begun to walk again and soon reached some woods on the upper edge of the North Saskatchewan River Valley. The moonlight brightly illuminated a winding footpath through the scrub poplar, birch and crisscrossing windfall and deadfall that I had taken many times. It was only a short passage, perhaps two hundred yards, and ended at a flight of wooden steps dropping fifty feet to the broader paved valley trail below.

Standing there in the full moon’s glow, thinking about Christopher Knight, I recalled something from the book that Finkel eventually published about the Hermit of North Pond. Knight (ironically, given his name) feared nothing during his hermitage as much as he feared a full moon. In his own words, he had to deal constantly with the “moon question.” Considering that his hermitage, expertly hidden as it was behind a great boulder and under much dense foliage, was so close to some cabins that he could often hear people talking, Knight couldn’t take chances by foraging in moonlight. He required a deeper darkness, just as he had required a deeper something when he stood, as I stood now, at the entrance to some woods.

Here were Robert Frost’s two roads diverging in a yellow wood, even though this forest was Brothers-Grimm-black and the road only a single trail. Without question, I was at a crossroads, on the verge of taking the road less travelled, just as Knight had done. But I didn’t have to make a decision yet; in fact, I was still exploring, still more in the human world than out of it. Even so, I hesitated, almost as if I was Knight in 1986, the nuclear flames of Chernobyl far back over my shoulder and a seductive, dangerous stillness somewhere in the mysterious and ancient hush of the trees. Somehow, to go along the trail now, as I had done hundreds of times before, seemed like a commitment to a different trail entirely.

________________________________________________

Tim Bowling is the author of twenty-one works of poetry, fiction, and nonfiction. He is the recipient of numerous honours, including two Edmonton Artist Trust Fund Awards, five Alberta Book Awards, two Writers Trust of Canada nominations, two Governor General’s Award nominations, and a Guggenheim Fellowship.