"Writing Poetry... Means Companionship for Your Whole Life" April Writer-in-Residence Leah Horlick on Composting Poems, Favourite Reads, & One Hero Teacher

Dayne Ogilvie Prize winner Leah Horlick's third poetry collection, Moldovan Hotel (Brick Books), has been hotly anticipated for a reason: it showcases a poet at the top of her game, delving into deeply personal history to draw universal truths.

After travelling to the region of Romania from which her Jewish ancestors fled persecution, Horlick created Moldovan Hotel, packed with poems that are informed by history but which simultaneously feel immediate and timely. Intense and wise, the poems discuss revolutions and revelations, guilt and power, politics, gender, and more. In Horlick's hands, this intimidating subject matter is expertly distilled, with an overarching feeling of clarity, toughness, and insight.

We're incredibly excited to announce that Leah will be joining the Open Book team for this April as our writer-in-residence, sharing original writing on the site throughout the month.

Get to know her here, as we chat with her as part of our Poets in Profile interview series, and stay tuned to our writer-in-residence page throughout April to hear more from Leah.

Here, she tells us about an influential and heroic teacher of hers (whose story has an excitingly happy ending), how she "composts" poems as part of her writing process, and tells us the best part about writing poetry.

Open Book:

Can you describe an experience that you believe contributed to your becoming a poet?

Leah Horlick:

My family and I lived in a series of very small towns when I was growing up, but we spent every summer (and many, many weekends) living with both sets of my grandparents. All four of them were avid readers, loved poetry, and let me read anything I could get my hands on—which was especially ideal for a very early gay like me. I didn’t have any friends in the city where they lived, and so I spent most of my time out of school wedged into a perfect kid-sized spot between the wall and a very large bookshelf. I also had an especially tremendous English teacher for fifth and seventh grade; she felt very strongly about reading out loud to us, and gave us vast amounts of silent reading time in class. (Perhaps unsurprisingly, she is also the teacher who intervened when I was being beaten and harassed by homophobic classmates. Last year I learned that she had since become the mayor of that particular small town, and I cheered aloud.)

OB:

What one poem—from any time period—do you wish you had been the one to write?

LH:

How to choose?! There’s so much, and to be the writer of some of my favourites, I would have to be a completely different person. That said, I don’t think I’ll ever stop thinking about this piece by Jameson Fitzpatrick, a poem with which I feel a great kinship. It’s a feat of time travel and form, and would have made a huge difference to me had I found it earlier in life. I am fairly certain it crossed my path via a share by Zoe Whittall – thank you, Zoe!

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

OB:

What do you do with a poem that just isn't working?

LH:

I am a strong proponent of putting stuck poems away in a folder or a drawer, and leaving them for a long, long period of time. I usually call this “composting” and trust that anything unnecessary or re-usable will break down when I come back to the piece with fresh eyes. Some of my best work has been done after leaving a poem untouched for multiple years.

OB:

What was the last book of poetry you read that really knocked your socks off?

LH:

Grey All Over by Andrea Actis, who is part of the spring catalogue with me at Brick Books this season. As someone whose life has also been profoundly impacted by the unexpected death of a loved one, I am astounded by how Actis has captured the materiality of grief through photos, recordings, and notes, and moved by the absolute determination of her text to confront how we treat what’s left of those we love. We’ll be part of a book club event together with Brick later this spring (stay tuned!) and I’m so looking forward to learning more from her. I also think often, and with awe, about I Am Still Too Much by Brandi Bird, East and West by Laura Ritland, and Everything Is A Deathly Flower by Maneo Mohale.

OB:

What is the best thing about being a poet... and what is the worst?

LH:

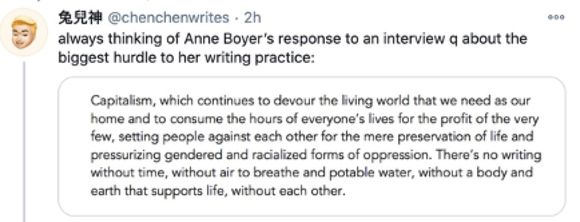

The worst thing—well, some of those things I’m looking forward to exploring with you in my residency for Open Book! But speaking broadly, it’s the precarity, perhaps best summarized by a quote from Anne Boyer that I found shared in this tweet by Chen Chen:

As for the best thing: I think writing poetry—but also loving to read poetry, whether or not any writing is happening—means companionship for your whole life. The companionship of your own book, or a single poem, or a way of looking at the world, or being surrounded by work you love, written by people you care about and respect: that’s the best.

_________________________________________________

Leah Horlick is a writer and poet who grew up as a settler on Treaty Six Cree Territory & the homelands of the Métis in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. Her long-awaited third collection of poems, Moldovan Hotel, is available now from Brick Books. Her first book, Riot Lung (Thistledown Press, 2012), was shortlisted for a 2013 ReLit Award and a Saskatchewan Book Award. Her second collection, For Your Own Good (Caitlin Press, 2015), was named a 2016 Stonewall Honour Book by the American Library Association. She is also the author of wreckoning, a chapbook produced with Alison Roth Cooley and JackPine Press. She lived on Unceded Coast Salish Territories in Vancouver for nearly ten years, during which time she and her dear friend Estlin McPhee ran REVERB, a queer and anti-oppressive reading series. In 2016, Leah was awarded the Dayne Ogilvie Prize for LGBT Emerging Writers. In 2018, her piece "You Are My Hiding Place" was named Arc Poetry Magazine's Poem of the Year. She lives on Treaty Seven Territory & Region 3 of the Métis Nation in Calgary.