A Passage to Academia

By Koom Kankesan

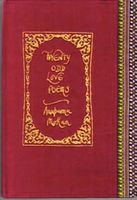

I cannot separate Anupama Mohan from the context of school. I met her in university while she was completing her PhD. A fan of film, Shakespeare, and critical theory, she impressed our professors, took her research in colossal strides, and was an inveterate reader and thinker. Both confident and expressive, self-conscious and sensitive, Anupama was a study in contrasts. This was partly due to the many cultures and cities she had experienced. Academic settings are never as neutral or tranquil as their outward appearances suggest, and Anupama braved them with vigour and aptitude. Most of our discussions were spent on film (with a special fondness reserved for Satyajit Ray), books, and the experience of navigating university. I cannot think of my grad studies without an associative memory of her popping into view.

Now she is an English professor: in the same city where Satyajit Ray lived and worked. A short teaching stint in Nevada led to her position at Presidency University in Kolkata, in the West Bengal. I talked to her amidst the culmination of Presidency University's bicentennial celebrations.

Koom: You are a very involved English professor at Presidency University. How do you find this balances with your own interests and aims as a poet/creative writer? Does being an academic become a hindrance to being a creative writer, either psychologically or practically?

Anupama: The work of a professor, to my mind, parallels (and does not quite intersect with) the goals of a poet/creative writer. In my mind, the critical labour I provide in classrooms does take a great deal of time and energy away from my creative work, and there is always a degree of tension (in my mind) about this. I think, though, I also nurture the tension because sometimes time stolen away from professional work can become productive (I once wrote two short stories during a particularly gruelling few weeks of grading and an academic deadline), but in general, I know I cannot devote myself to creative writing as a full-time profession. Part of the fear is that I am not good enough, and the other part is the very real economic and material fall-out of such a decision. But fear is not the only thing keeping me back: I love some of the work I do as an academic and I love introducing students to new ideas and walking with them through the maze of contemporary events with literature providing the map for taking that walk. And clichéd as it sounds, I truly enjoy the process of writing critically – it is, to me, a responsibility and there is a certain sacredness to the art of being critical, rigorous, and regenerative of new interpretations that is very addictive. So, I’m in a constant state of intellectual disbalance, if I can put it like that, but that makes the striving for balance the point of one’s intellectual life. I don’t know if I could handle balance itself and perhaps, the best kind of balance is always contingent and rare.

Koom: I find the element of fear that you mention an interesting subject. Of course, fears about talent and sustainability are pressing anxieties for many would-be writers. When I knew you at the University of Toronto, you seemed to be a most fearless academic. You were expressive, analytical, and took theory in stride. What is it, do you think, that makes you extremely confident when it comes to academia but more tentative when it comes to creative writing? Are there two different centres of our brain that correspond to these things, or perhaps two different centres of our psychological/emotional being?

Anupama: You know, I think, in my case, I definitely imagine my mind (brain plus heart?) as working on two distinct impulses: the rational, logical side of me loves abstract ideas and thinking conceptually and finds great comfort in understanding the world as a series of structures, sometimes connected but mostly chaotic and requiring ordering and interpreting constantly. And there is a different side of me that I allow: a kind of manic energy, incessantly observing people and life, converting outsiderliness into inwardness and reflexivity. This other side, I draw deeply on when I am writing poetry and fiction, but it is not an easy facet of oneself to master. In the short story “Down, Across,” I see the coming together of both the academic and creative sides in me—the frame of the crossword orders my impressions of a city but also converts an exteriorized portrait into an inward space. But when I wrote “The Gift,” things went out of control, I think, and it became a tussle between the critic-theorist who saw connections across cultures and languages, and the imaginative writer who wanted to stand apart from that web of connections to produce something startlingly new.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

So, I am aware that thinking of one’s mind as twinned in this way is itself a reflexive exercise and I don’t want to draw too fine a boundary, as if I was always aware of the two roles and their ambits. Writers like David Lodge or Edward Said are, for me, great examples of writer-theorists who have honed an authentic, lucid voice across different genres of writing. The voice that brings alive Out of Place (Said’s memoir) is the same that insistently warns us of the very real historical dangers of Eurocentrism in Culture and Imperialism. As for Lodge, I remember this great footnote in his canonical book Modern Criticism and Theory (my go-to theory book during the 2000s as a resource-strapped student in Delhi University) where he explains jouissance (in Helene Cixous’ essay “Sorties”) as “that intense, rapturous pleasure that women know and which men fear.” It’s the kind of cheek by jowl sprezzatura (no fear!) between his critical and creative commitments that you also see in Lodge’s best fiction.

I don’t think of my academic life as fodder for my creative work, and my creative work is itself beholden to a constant critical surveillance upon the world and myself. Does that make sense? I’m guessing that you are not immune to such dichotomies yourself.

Koom: I have to be honest and tell you that the two facets of my life are fairly divided. For the last five years, I have taught high school during the Fall semester and taken a leave without pay for the Winter semester in order to write creatively. It's a very seasonal cycle and not one I'd particularly recommend, but it worked for me. Now, my teaching duties are different from yours as I teach high school but I found I cannot write sustained fiction while teaching. And when I write (you can probably tell this from reading some of my intros to other interviews), I completely forget that I'm a teacher. My personality slips off its pedagogical coil and adopts a much freer, broader, playful perspective. So, for me, the two areas of myself/my brain which harbour these activities are very separate. The ground between the two would be when I read (especially for pleasure) or learn in order to feed personal, curious drives.

I am glad that you are maintaining your creative writing practice despite the various duties you have to contend with. What is it like to be a hopeful (nascent?) writer in Kolkata where you live, or India generally, and a woman writer at that?

Anupama: Let me answer this question in terms of the two hats I wear: as an academic-scholar and as a creative writer. As a scholar, I feel the move to India has paid off in personal terms, but not yet in professional terms. As you know, my husband and I accepted jobs in the same university and moved to India in order to bring an end to our separated-lifestyle in North America. On that count, the move has been great. But in professional terms, the competitive edge is gone, as the Indian higher education system is completely different and presents a whole other set of challenges and opportunities. Being in Kolkata, while exhilarating in many respects, has also been testing because entrenched academic coteries rule various roosts and my particular university is often the focal point of conflicts arising out of different vested interests. As a non-Bengali myself, I am late in picking up social/linguistic cues and tend to mis-read many things – but thanks to merciful friends and colleagues, I am rescued from a contretemps turning serious! Overall, I remain mainly committed to the welfare of my students and to working away at my own research (which has increasingly become pushed into a strained space), so I tend to isolate myself from such things, although one can’t always remain distanced. Choosing one’s battles and exercising self-restraint has become a big part of my public, academic life.

For the creative writer side of me, Kolkata in particular, and India, more generally, are great checks to a purely Anglophone life: in my years abroad (2004-2013) as a student and then an assistant professor, life was overwhelmingly “English” – it was both my language of daily discourse as well as, of course, my language of professional exchange. I had not ever, prior to 2004, spoken or worked “inside” English so much as I did when I lived abroad. The social register of English language became stronger in my mind and in a way, the colonial distance narrowed.

Now that I am back in India and am bombarded with the sounds of myriad tongues on a random walk to the grocer’s, that cocooning in one language disappears – and this is a great re-orientation for a writer. On any given day, I speak four languages without even trying (English, Hindi, Malayalam [my “mother-tongue”], and Bengali) and then, given the composition of the city and its people, there is a slew of other tongues constantly aswirl in the air that I tend to pick up on: Bihari, Bangladeshi dialect of Bengali, Tamil, and Marwari, among others. I still speak many hours of English daily (and write almost exclusively in it), but I live and work with the strong consciousness of many language-worlds, and the fusions and frictions amidst these different registers have become central to my creative writing style.

The current creative piece of fiction I’m working on (genre undefined as yet) is a paean to this spirit of surfeit. It is difficult to capture this in prose and particularly for my own writing, I tend to often feel dissatisfied with fiction (I’m a lot more comfortable writing poetry, esp. terse, craft-centric verse) because I feel that all I am doing is to expand a poetic perspective in many words! So, that aspect is still work-in-progress. As for being a woman writer, it is not an explicit side to my creative writing, I think, but certainly, as an academic and a thinker, I am a feminist and a certain fluidity towards expressing sexual identity marks all my thinking and writing.

Koom: Your response makes me want to ask two questions:

1) Can you expand upon the last sentence and explain in more detail or perhaps give us some examples: 'I am a feminist and a certain fluidity towards expressing sexual identity marks all my thinking and writing'

2) Why write prose at all, given that you find poetry a better vehicle to express what you want? There certainly was a belief among some that poetry is the purer art because it achieves the goal of expressing mysteries and those things which are abstract more readily. It is also more succinct and (perhaps) more imaginative in terms of craft and structure. If you have a leaning towards it, why go to prose at all? Some people see prose as crude and limited in comparison to poetry.

Anupama: By fluidity towards expressing sexual identity, I mean, that in my writing, I tend to approach the question of (individual) identity as intersectional: here, the gender dimension itself is not paramount (although never insignificant) and I am more interested in exploring civic subjects in the fullness of life’s realities. What does it mean, for instance, to be a young urban woman who grew up in conditions of material want but with strong aspirations towards class mobility? Such a creature (and I see a lot of myself in such a figure) is not imaginary and yet so ubiquitous as to be almost invisible, until you rub her against someone utterly different: a spry, lower-class working woman who is not yet 25 and has three children and cleans seven homes a day to earn the living that will put food on her table and help her stand strong against the assaults of a delinquent spouse. It is not easy here to merely see things through a gendered perspective; what is needed, if we are to not reduce people to immutable essences, is the ability to see identity in flux. How is writing to capture such dynamism without mystifying it or resorting to obfuscation? And yet, there is a beauty to all labour and while as an academic, I am committed to communicable social change, I am also, as a writer, capable of seeing and sharing the beauty and pleasure in all kinds of life.

Why write prose? Why not? I tend to be a generalist in my interests and I have a strongly empirical will. My poetry is itself cerebral, even when it is about love or sexual desire. In that sense, my poetry is not the spontaneous overflow of feelings or written when I am tranquilly sitting around in a vacant or pensive mood. I am also very fond of the volta as a technical device and love stories that have a convincing and unpredictable volta. Prose allows me to explore forms and modes not usually available in poetry, and the kind of poetry I enjoy (and write) also tend to be explorations of unusual forms – e.g., I enjoy reading A. E. Stallings, who is a really atypical poet, and recall with great pleasure my first reading of Vikram Seth’s The Golden Gate, a novel in verse. So, my stories which give me great trouble and require much effort – and therefore, in a masochistic way, are very enjoyable to produce – tend to be vignettes, have a volta of some kind, and explore a single train of being captured at a particular, fragile, intersection of time and space. “The Interloper” published in Caesurae is just this kind of tale. You’re a novelist: do you tend to just write long pieces or do you begin with something small and see where that takes you? I tend to work with snapshots of what I want to convey and I find that a certain kind of brevity and compactness gives me great pleasure – I don’t know how to push past this pleasure to write a novel, really. Which is why I am fascinated by novelist-researchers because I think I could write a novel from out of time-consuming and laborious research (a process I enjoy anyway) – a thought that so many writers who write by sheer inspiration might find odious!

As for the toss-up between poetry and prose, I think, it’s a spurious dichotomy. In terms of stature, each has its hallowed ground: if the epic poem has a historical grandeur that remains fairly universal, the novel has gained and kept vast ground since at least the 19th century. Indeed, if you think “postcolonial,” you think, alas, only of the novel really. But as a scholar, I know that genres are really expressions of the power of some social forms over others and are themselves political (and not incidental) choices. If I write a novel some day, it will be only because I am confident that it will make a difference in the life of a reader – it may, eventually, not make any such difference but I will feel impelled by the thought that it can/might. Otherwise, it’s not worth the upheaval.

The author photo attached to this post was taken by Deborah Achtenberg.

The views expressed in the Writer-in-Residence blogs are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Koom Kankesan was born in Sri Lanka. While his family lived abroad, the civil war in Sri Lanka broke out and this caused them to seek a new home. They eventually settled in Canada and have lived here since the late eighties. He has a background in English Literature and Film Studies. Koom contributed arts journalism to various publications before becoming a high school teacher in the Toronto District School Board. Since working as a teacher, he has taken semesters off now and again to work on his fiction. The Tamil Dream, his new book, is his most ambitious to date. It looks at the end of the civil war in Sri Lanka and how it affected Tamils here in Canada. Besides literature and film, Koom has deep interests in history and science, and an enduring love for comic books.

You can write to Koom throughout January at writer@open-book.ca.