Canadian Melancholy

By Koom Kankesan

During the nineties, barely out of teenagehood, I walked up to the run-down apartment building in Cabbagetown where Seth lived. I rang the bell and when he answered, in shirt sleeves and suspenders naturally, I asked him if I might learn cartooning by helping him: I could draw the clouds in the background of his panels, I said, for example.

Yes, that's right: I am an idiot.

Fortunately for me, Seth did not respond with a high-pitched sardonic laugh, or punch me in the face (as Dan Clowes or Peter Bagge may have done). The consummate craftsman did not need help with clouds or birds or speech balloons, but he did offer to teach me a little about comics. He assigned me small projects - to draw two or three page stories - I tearfully struggled through this homework, and then Seth, very graciously, critiqued them. My efforts were shoddy. Seth was too much of a gentleman to admit it during our meetings at the Jet Fuel café. Sometimes, others would be there. Seth dispensed opinions freely: comics, what made them good, and what he didn't like. His influences, both recognized and forgotten, were vast. A few years later, Drawn and Quarterly exploded into a powerhouse and Seth became a Canadian icon. A page of his was said to hang at the AGO. He illustrated for The New Yorker. His immaculate design appeared on the dust jackets for books relating to The Vinyl Cafe. The fact that he didn't react to the last assignment by digging a shallow grave, and bringing solace and much needed silence to CBC radio listeners on a Sunday afternoon, speaks to this man's professionalism and courteous nature.

One of my deepest regrets is that I didn't take full advantage of the generous opportunity presented to me. I was too self-conscious of my poor artistic skills. More a fan than an artist, I sat at his table while he tipped his olive fedora at the masters who had gone before. The process did, however, shift the way I looked at comics. I saw it as a medium that did things rather than a set of pictures that told a story. It dawned on me... of course a good cartoonist drew his own clouds! He did not separate the art from the writing the way production houses had done. Seth got me to read the independents, and then the classics. He got me to appreciate comics artistry before it was cool to do so.

Thus, being able to catch up with him years later means the world to me. The author photo attached to this blog post was taken by Nigel Dickson. All of the images below are, of course, Seth's.

Koom: There's a strong strain of melancholy in the work that I've read by you. Sometimes it's quite beautiful, while at other times it tilts into full-on despair. Is this something you feel still, truly, in your own life or do you push the 'colour balance' of emotions in your writing towards that emotional spectrum? If it's pushed, why do you go for that? If it's an authentic expression of your own life, how do you manage to keep up your pace of work - illustration and personal comics - under a condition that, frankly, many writers and artists have to contend with?

Seth: Yes, the work is always melancholy. It’s not accidental but it's certainly not entirely contrived either. I am a very melancholy person and I write in that tone because I always feel it. However, I have to state pretty strongly that there is a huge difference between melancholy and depression. I am not a depressed person in the least. I’m actually a very generally content person. I rarely fall into real despair any longer (I was certainly more emotionally ragged in my younger days). I would go so far as to say that this is the happiest time of my life —without a doubt. Being happy though is not the opposite of melancholy. I’m not even sure that melancholy is entirely sad. There is something pleasing about wistfulness. I think this might be the meaning of the phrase “good grief”. It is grief, yes… but it is not a terrible grief. Just a little one.

I always miss things. I miss people. I miss times in my life that are gone. I don’t feel depressed about this. Just pleasingly sad. I think this good grief permeates every aspect of my life. I enjoy things more when there is some element of this feeling involved. Maybe it’s a bit of a fetish. Or a character trait. Or a gene for longing. I don’t know. I do know though that I cannot write a story that has none of this in it. Sometimes my stories are a bit grim or remorseful. That might be part of getting older. But, if I think about it, I’ve pretty much always felt this way: a love of isolation but a fear of loneliness. A desire to be in the world but not of it. A turn of mind toward that which is passing away. Some sense of contrarianism that keeps me from joining the main culture.

And, to answer your second question: this kind of pleasing sadness in no way inhibits doing the work. In fact, it is a boon because it keeps me in my studio. In the studio, I try to create a kind of emotional bubble that wallows in this range of emotions. I mope about and fiddle with one project or the other... trying to keep time at bay.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

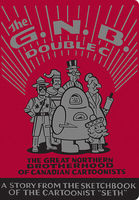

Koom: I think you are right: there's certainly a sweetness to melancholy longing. Wistfulness can be especially pleasurable. When I knew you a little in the late 90s, you seemed very garrulous and opinionated, a bit of a smart aleck, not depressive at all. However, your 'autobiographical' comics didn't seem to have the same sprightliness. It would be years before I realized that your autobiographical 'quest for the forgotten cartoonist Kalo' was entirely made up. There was the missing mercurial element - it was all fiction - masquerading as autobiography! I wonder whether your affectation of nostalgia might simply be a way of constructing a vision that never existed? You may be constructing an ideal Canadiana that is more utopian, and therefore more about the present than the past? The G.N.B.C.C. is another example of this wistful but ultimately fictional Canadiana.

I'm glad that this is the happiest time in your life. Would that all times we currently find ourselves in were the happiest! How does your happiness affect your productivity? Does it dull the whetstone or simply make it more joyous to produce?

Seth: You are very right in that I'm not actually one of those "nostalgia guys" who romanticize the past. I have no illusions about the past (well, not too many). I do not wish to live in 1920 or 1930 or any earlier time. I am repulsed by much of today's culture but I don't kid myself that things were any better in the past. Every era is fraught with problems and injustice and vulgarity.

So, yes, what I am interested in doing is constructing my own inner worlds. Sometimes, they are direct wish fulfillment (like my city of Dominion) and sometimes they are more fanciful (like the fake Canadiana of GNBCC). You nailed it with your understanding of my relationship to Canada. I wish to reinvent it for my own needs. I pick and chose what appeals to me and construct my own narrow picture. My Canada is pretty much a Canada that never existed. It's a jigsaw puzzle in which I have left out a lot of pieces. I'm not a historian (nor am I all that interested in History in a deep sense). What interests me is "sense of place" or what makes up identity. Iconography. Atmosphere. Vague things often. But this stuff is great for world building. Dominion is a place made up entirely of whatever strikes me as evocative. It's not an ideal place where everything is "perfect". Instead, it is composed of everything that draws my attention. Often, those are sad things - decay, dissolution... the winding down of those eras in the past that I'm aesthetically attached to. It's a place almost entirely devoted to building atmosphere (much of this detail is in my notebooks or in my head). The worlds I'm building are idealized in the sense that they do not contain any elements of the "real" world that do not interest me. Consequently, they feel out of time because I am not very engaged with the current era. As each year passes, I am refining my aesthetic. Coming to understand more clearly exactly what I am interested in. You'd be surprised how long it can take to actually figure out what is at the core of your artistic goals. I'm still working it out. In fact, the very next story I am starting (now that Clyde Fans is basically finished) will be written almost entirely with the intention of writing NOTHING into the story to appease the reader--to try to make it entirely for my own specific tastes. In other words, to write a story that would be the story I MOST want to read. Easier said than done.

As to the second part of your question: happiness makes my work better and makes me work harder. I have never much thrived on anger or depression. In fact, those darker feelings prevent me from working. My work is pretty much derived from self-indulgence. From a child-like desire for play.

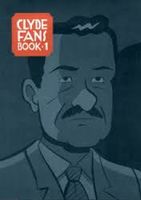

Koom: Hmm - there's a lot there that I'd like to respond to. First of all, congratulations on nearing the end of Clyde Fans. I remember that when you started this in the 90s, you were determined to take a slower pace, to not be constrained by the publishing limitations of the regular comic book. How do you feel about the project at this point? How do you keep fidelity with a passion project over decades?

Seth: I am surprisingly (modestly) pleased with the outcome. The final book is very faithful to my original conception of it. It concludes exactly as planned. Now, I have my qualms. The artwork is very inconsistent since it was produced over such a very long period of time. My storytelling skills increase as the book moves on... but that said, I'm relatively happy with the results. I still have to re-edit some of it and there will be a few new pages drawn, a few sequences expanded - but the work ended up being very faithful to my original vision. I think this is because, while I always knew every scene that would appear in the book, I did not write a script years in advance. I just patiently worked my way through the story page by page by page. It stayed fresh for me. It was always current work and not just some ancient project I had to "finish up".

Koom: It sounds like your next project is even more individualized and is determined to go further into your own predilections and sensibilities. Can you tell us anything about the scope and nature of this project? Do you worry about becoming indulgent or snapping the cord with your readership by going too far into uncharted territory? (I realize that this is very unlikely as you have one of the most solid and appreciative fan bases in indie comics today).

Seth: I won't go into details about the new story because that is always a mistake. Your plans change as you work on it and early comments can come back to haunt you. Also, speaking about a story before you do it risks getting lukewarm responses and this can undermine your enthusiasm. Best to keep your mouth shut. I will say that it will likely be a much shorter book than Clyde Fans. I am thinking that 150 pages to 200 pages is a more reasonable page count for me. We will see where it goes. I never worry too much about the readership following me. That's a dangerous game. Trying to guess what anyone likes to read is simply impossible and likely to turn your thinking into a pretzel. What one must do instead is shore up your belief that you are always right. That sounds odd and aggressive but what I mean by it is that you must have pure confidence that what you think is interesting will translate to someone else's interest. I have generally found it to be true. When we published Wimbledon Green, I was very doubtful that anyone would care for it. It was such a personal and silly project. Yet, as the years have passed, I have found that book to be increasingly popular. People who like none of my work often like that book. I wasn't even sure if I wanted to publish it at the time. I liked it... but I thought it was clearly geared toward my own self-indulgent tastes. You never know. My one genuine concern for the reader is that I always try to make the work clear and understandable.

I trust the readership to follow me. I trust that I am getting better as an artist. I trust that the best work is still to come. Indulgence is the only clear path for the artist.

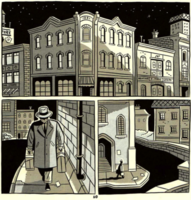

Koom: I'm curious about the physical practice of your drawing/cartooning technique. Your work in recent years has become more visually patterned and tiled, for lack of better terms: smaller panels, intricate grids, a high degree of orchestration. Simply looking at some of the pages before reading them is an arresting experience, in and of itself, due to the mosaic-like metronomic design. I'm thinking of Clyde Fans in particular, but it applies to your other stuff too. The storytelling/plotting/element of time follows, your sense of design leads. Has this become an intentional move away from the earlier comics which were more mainstream in narrative and pacing? If so, why?

Seth: Bit by bit, I feel I am moving away from the concerns of traditional cartooning in my drawing and storytelling. I'm not much interested in drawing to be honest. I am very interested though in design and composition. Because of this, the drawing is becoming more and more minimalistic. I suspect in my next book I will be trying to boil everything down to the least amount of detail I can. Bold shapes and lots of black. There is always a desire, somewhere in a work, to pull out some complicated drawing just to impress... and I am sure I will give in to this impulse here and there (sometimes, it's required to give the story impact too) but generally, I see my work getting simpler and simpler. What really excites me now is how well this process of simplification combines with the kind of storytelling I'm trying to do (ie: a lot more narrated voice-over). It's interesting as well that the simpler the drawing gets, the more complicated the page gets (more panels especially). So yes, this direction is an evolution away from the more naturalistic storytelling style of Clyde Fans.

Koom: I'm also curious about your line, which is highly controlled and strong. It almost has a chunkily beautiful curve to its flow. How do you keep such strong control over your line? Especially on such smaller, tightly structured, panels? Isn't it harder as you get older and stiffness of the joints sets in?

Seth: Truthfully, bit by bit, I've also been abandoning my more beautiful brush lines for simpler and colder approaches. A lot of pens and rulers are starting to be involved. Even in the sketch work like Nothing Lasts, most of the drawing is just in simple magic markers. This is kind of surprising (even to me) because I worked so hard for years to develop a facility with the brush. I deeply loved the best brush cartoonists in my youth and I wanted that quality of skill myself. Now, I don't know. In some ways, there is something a little distracting about the brush line in a comic story. I want the work to be simple and direct. Sometimes, that means sacrificing some of the surface beauty. That might just be a rationalization though. You follow certain paths simply because that is where your interest leads you, and then make up good sounding reasons for it later. All I really know is that my artwork is becoming tighter and more mechanical. Much flatter and less evocative. That might be a mistake - people respond to that sensual brush line. Who knows?

Koom: I am a little sad to hear that you're going more tight and mechanical with your style. It occurs to me that Jaime Hernandez's style shifted that way somewhat in the 90s although I wouldn't say it became mechanical. Adrian Tomine's has moved into a much more hyper-design sensibility too, although both of these artists were very concerned with design from the get-go. In all of these cases, it's heartbreaking to look at the earlier ripe, almost earthy work in comparison and not feel a pang for that period. Filmmakers often get more spare and restrained too as they proceed. Besides the growing design sensibility, I do feel you've gotten more expressive with your facial expressions and lines somehow. Perhaps the earlier stuff had more detail but I feel you've developed the ability to convey expression really tightly and strongly now. Beads of perspiration are in exactly the right place. The facial muscles draw out exactly the right grimace. With the strong brush line, it's more powerful a style than what I remember of your earlier work. However, I was talking to Jaime for another interview in this series and as I was re-reading some of his stuff from the last decade or more, I really appreciate how lovely and precisely timed the cartooning lexicon is. He eschews roundedness, texture, and detail for this precise syntax that just sings!

My final question is about Canada and being Canadian. For better or for worse, you're a Canadian cartooning icon. How do you feel about this? With what aspects of the Canadian psyche/identity do you identify? It is our 150th anniversary after all. Also, a line from G.N.B.C.C. really stuck with me when I read it - something about the gentle roll of the southern Ontario landscape. You described it as a very subtle character and only people who had grown up here would recognize it or feel it, or at least that was the suggestion. I've lived here for thirty years and I've only just begun to sense it. Can you talk more about this sense of southern Ontario - what is it, and how do you try and transmit it in your work?

Seth: I do identify very strongly as a Canadian. I love Canada and even though I have visited some pretty beautiful places in the world, I feel very attached to Canada and cannot imagine ever leaving. I am connected to Ontario, specifically. Mostly, of course, because this is where I grew up and have lived all my life. There are more beautiful places in Canada to live (without doubt) but familiarity is an underrated quality. I love the familiar. You made mention of my comment of the "rolling hills of Ontario". It's a good example. The "texture" of a place gets under your skin. It is often so under the skin - so familiar - you almost don't notice it. The shape of the land. The colours of the night sky - pearly white against the silhouetted trees and barns. The electrical towers "marching" across the landscape. There is something beautifully familiar in every little Ontario downtown I drive into. Those main streets have a hang-dog look to them that appeals to my aesthetic very strongly.

In fact, I think my aesthetic is almost entirely formed out of mid-century Ontario (with a good dose of American art Deco). I don't think I understood when I was younger that this was the source of my artistic "muse" but year by year, it becomes more evident. Now, when I look back at my first graphic novel, It's a Good Life if You Don't Weaken, I see that right from the get-go, I was trying to articulate something about Ontario. And Toronto, of course. My work is probably becoming less urban since I've been away from Toronto for about 17 years now (which I can hardly believe). When I return to Toronto, I feel somewhat alienated from it. It's changed a lot. It reeks too much of the modern aesthetic to me... but I still see plenty of old Toronto peeking out here and there. I liked that old Toronto. When I moved there in 1980, it still had a strong feel of the mid 20th century about it. Not so much any more.

I guess, in a nutshell, what I want to say about Canada is that I do feel emotionally attached to it and I do wish to infuse my work with a quality of what it feels like to live here. There is something inherently Canadian in my work and I focus on that. Try to highlight it. But, of course, that would be true of a lot of artists in a lot of different places. Where you live informs what you do and how you think. The countryside and towns and cities of Southwestern Ontario are right at the core of what I do and how I think.

By the way, I love the way, as well, that Jaime has pared down his approach over the years. No one can draw the figure so deftly and understands gesture so perfectly. He gets better every year. Adrian too.

Take care and thanks for the thoughtful, smart questions!

Koom: My pleasure! And please don't hesitate to ask if you ever need help with those clouds!

The views expressed in the Writer-in-Residence blogs are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Koom Kankesan was born in Sri Lanka. While his family lived abroad, the civil war in Sri Lanka broke out and this caused them to seek a new home. They eventually settled in Canada and have lived here since the late eighties. He has a background in English Literature and Film Studies. Koom contributed arts journalism to various publications before becoming a high school teacher in the Toronto District School Board. Since working as a teacher, he has taken semesters off now and again to work on his fiction. The Tamil Dream, his new book, is his most ambitious to date. It looks at the end of the civil war in Sri Lanka and how it affected Tamils here in Canada. Besides literature and film, Koom has deep interests in history and science, and an enduring love for comic books.

You can write to Koom throughout January at writer@open-book.ca.