Catholic noir. Yes, it really is a thing!

By Lisa de Nikolits

I went to a convent for most of my school life. McAuley House, run by The Sisters of Mercy. McAuley House was memorable primarily because I was kicked out of confession unabsolved, for not confessing the 'correct sins'. Then the nuns left the convent so my parents sent me to an Ursuline Convent, Brescia House. This did not turn out well and I was expelled for pedantic and tedious reasons and I spent a summer reading under a tree while they all sorted it out. But, to the point of noir, if you're once a Catholic, you're always a Catholic and so today, we will be looking at Catholic noir.

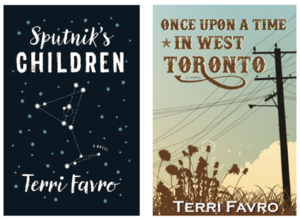

No one does Catholic noir better than Terri Favro and I was simply delighted when she agreed to write about the topic. I'm sure most Open Book Toronto readers are familiar with Terri's work but in case you're not, Terri is the acclaimed author of The Proxy Bride, (Quattro), Sputnik’s Children, (ECW), Once Upon a Time In West Toronto, (Inanna) and she has many other writing accolades.

I asked Terri to tell us about her take on Catholic noir; I asked her to explore and talk about the undercurrents of loss and punishment, the rituals, how it ties into a community and how it can shape the imagery and themes of a story, and I thank her for this excellent post. I hope you will enjoy it as much as I did! And P.S., you don't have to be Catholic to enjoy or relate to the post – religious noir is something we are all familiar with, I am sure, in whatever specific form it may take for you. (And then there's atheist noir...but not today!)

Flesh and the Devil: Catholic Noir by Terri Favro

Although lapsed for many years, I was born and raised a Catholic. Starting at age seven, I spent many a Saturday afternoon inside a church confessional. Queasy with guilt, I’d push aside the heavy velvet curtain and kneel in the darkness to recite a ritual prayer I’d repeated so often that the words bled together:

BlessmefatherforIhavesinnedit’sbeenonemonthsincemylastconfessionandthesearemysins.

Note the last syllable: sin. That’s the central concept of any Catholic noir story.

On the other side of the Confessional’s interior grillwork screen, a man –– well, not a man, technically, but God’s ear ––listened, as I whispered my sins into the void between us.

I knew that at the end of the Confession, I might be forgiven. Or I might be punished (by being required to kneel in the church and say a hundred Hail Maries, for example). Likely, I’d be both forgiven and punished. And if that isn’t noir, I don’t know what is.

Despite what mafia hit men believe, Confession is not a get-out-of-hell-free card for sin. There are no do-overs, no mulligans. You have to actually regret the fun you had being bad and intend never to succumb to the temptation to do it again.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

Yeah, right. Tell that to insurance adjuster Fred MacMurray in 1944’s noir masterpiece Double Indemnity, driven by lust for Barbara Stanwyck to kill her husband and cover it up. Or the flawed, conflicted characters in noir films like L.A. Confidential, Chinatown and Bladerunner.

Sometimes (okay, usually) being bad just feels good. Or at least right.

Whether a literary thriller like The Maltese Falcon, a Hitchcock suspense movie like Strangers On A Train, or young Terri confessing her sins on a Saturday afternoon, the narrative arc of a Catholic noir story can be summarized this way:

Temptation. Sin. Remorse. Forgiveness. Punishment. Repeat.

Why “repeat”? Why do we keep sinning and sinning and sinning, when we just end up on our knees in the confessional, which should act as a moral Fit Bit?

The devil makes us do it. In Catholicism, the devil isn’t an abstraction. It’s a being, and there’s a pretty good chance it’s a glamorous blonde of the type that mystery writer Raymond Chandler famously wrote, “would make a bishop kick a hole in a stained glass window”. Or, if the devil takes the shape of a man, it might look like Dashiell Hammett’s hardboiled detective Sam Spade, described in the noir mystery classic The Maltese Falcon as “a blond Satan”. (Hammett was a Catholic. At least he started out that way.)

At my baptism, my godparents were required to speak on my behalf. They were asked to “denounce Satan, father of sin and prince of darkness...and all his works”, including “the glamour of evil”. But despite those denunciations, I eventually discovered that glamour, evil and sin are always just one Singapore Sling away.

I left the church a long time ago for a lot of reasons. But, as they say, once a Catholic, always a Catholic. As a writer, my religious upbringing was a gift. The characters in my novels The Proxy Bride, Sputnik’s Children, and Once Upon A Time In West Toronto, all explore dark mysteries of the soul, including the blurry line between good and evil; the compulsions and obsessions that drive us to act on our worst impulses; the guilt that ensues; and our search for forgiveness and/or punishment.

The question in Catholic noir often comes down to: who exactly is the devil? Who can I trust? Can I make a deal with the devil? It’s the question that bedevils would-be priest Marcello in The Proxy Bride. He doesn’t know whether to trust his mysterious lover Ida, his abusive father Senior , or his sometime-employer, the porn smuggler Niagara Glen Kowalchuk.

In films, Alfred Hitchcock is at his most noirishly Catholic when an innocent protagonist is caught on the horns of a moral dilemma and doesn’t know who to trust. You see this confusion in Shadow of a Doubt and Vertigo, among other movies. But Hitchcock’s most on-the-nose Catholic noir film is 1952’s I Confess, in which a Quebec City priest (Montgomery Clift) is framed for a murder, by the murderer himself, who in turn has confessed to the priest. Why doesn’t the priest turn in him in? Because he’s bound by the seal of the confessional. The priest must either allow himself to be convicted of murder (and hanged for it), or betray his vows. To protect his immortal soul, he allows others to see him as the devil.

But sometimes, as in real life, the priest actually is the devil, as in the 2015 movie Spotlight (about the Boston Globe’s investigation of widespread sex abuse of children by Catholic priests) and Linden McIntyre’s 2009 Giller-winning novel, The Bishop’s Man (about a priest with a talent for covering up such scandals for the diocese). In these narratives, apparently pious men of God are sick to their souls, yet the “powers that be” in the church protect him instead of the children they have abused. Covering up a horrific crime is a narrative much used in noir – think of the corrupt police captain in L.A. Confidential, for example, or the incestuous tycoon in Chinatown. Or consider the subtle game of blackmail between the priest and nun in John Patrick Shanley’s 2008 stage play and movie Doubt: it’s never clear whether the priest’s sin was child abuse or of another type entirely, leaving the nun who accused him in an agonizing state of uncertainty. Or the 1985 film Agnes of God, the story of a Montreal novice nun who believes herself to have been raped by an angel named Michael, the resulting infant stuffed in a wastepaper basket in her convent cell to die.

These are the fiercely dark stories of Catholic noir. And many of them aren’t fiction.

While the devil is one aspect of Catholic noir, mortification of the flesh is another, especially in the mystery of stigmata, a phenomenon in which very devout people bleed from the parts of the body where the body of Jesus Christ was pierced during crucifixion: the palms of the hands, tops of the feet, and the right side.

Stigmata are one of the mysteries of Catholicism that has always fascinated me. In The Proxy Bride, Marcello develops stigmata on his chest —first, when he loses his virginity and again, when he falls in love with Ida, his father’s new bride by proxy. The idea of a blood sacrifice is very Catholic – you won’t find a Catholic church without a crucifix in it, which may vary in realism from a stylized figure on a cross to a carefully rendered image of a man being gruesomely tortured. That’s a noir trope too: the threat of grievous bodily injury. There’s a sadomasochistic appeal to all this violence, which can translate, in Catholic noir, to the elevation of suffering to an art form. Again, to quote from the writer Dashiell Hammet, speaking through his detective hero, Sam Spade, “When you’re slapped, you’ll take it and like it.” That’s a very Catholic statement. Physical suffering has long been upheld as a hallmark of holiness. Hagiographies known as Lives of the Saints were popular reading for Catholic kids like me and they didn’t stint on the gory stuff. Here’s an excerpt from Saint Agnes, Martyr in the “Miniature Stories of the Saints” by the Rev. Daniel A. Lord, SJ of St. Louis, Missouri, a hagiography I read as a child:

Agnes was only twelve when the Roman soldiers arrested her...they put handcuffs on her. She was so tiny that the cuffs slipped off her wrists.

Then they whipped her cruelly...Even the pagans wept to see her tortured that way.

Next they dragged her through the streets for the people to laugh at.

With one stroke of the sword, the soldiers killed this brave little girl.

In devotional artworks, saints and martyrs are shown with the instruments of torture that led to their deaths. St. Lucy carries a her gouged-out eyes on a plate.; St. Agatha, her severed breasts. St. Lawrence – patron saint of chefs –– grips the griddle that was used to roast him to death. This is why, when Marcello appears in a chapter near the end of Once Upon a Time In West Toronto, Lily turns and sees him at first as having the bruised face of a boxer, then imagines him as St. Sebastian, a martyr whose body was riddled with arrows.

Although long associated with mystery and suspense, noir is a mood than can infuse any type of story. As the word implies, it is a state of dimly understood desire and moral ambiguities, when temptation overrides conscience, and passion kills common sense. It’s what we see when our world cracks open to reveal the cosmic war between good and evil. It’s the flesh and the soul at war.

LdN: Thank you very much Terri, for this fabulous, insightful and thought-provoking post!

https://49thshelf.com/Books/S/Sputnik-s-Children2

https://49thshelf.com/Books/O/Once-Upon-a-Time-in-West-Toronto

https://www.inanna.ca/catalog/no-fury/

http://www.lisadenikolitswriter.com

https://49thshelf.com/Books/N/No-Fury-Like-That

The views expressed in the Writer-in-Residence blogs are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Originally from South Africa, Lisa de Nikolits has been a Canadian citizen since 2003. She has a Bachelor of Arts in English Literature and Philosophy and has lived in the U.S.A., Australia, and Britain. She is the author of seven acclaimed novels, including her most recent novel, No Fury Like That (Inanna Publications). She has won the IPPY Gold Medal for Women's Issues Fiction and was long-listed for the ReLit Award. Lisa has a short story in Postscripts To Darkness (2015), a short story in the anthology Thirteen O'Clock by the Mesdames of Mayhem, and flash fiction and a short story in the debut issue of Maud.Lin House.