Book Therapy: The Remembering Stone

By Stacey May Fowles

“But Alice didn’t want the perfect stone to sink to the bottom like all the others, so she put it in her pocket.”

-Carey Sookocheff, The Remembering Stone

For my family, last year was defined by loss. Over the course of only eight months, we said goodbye to my husband’s stepmother after a long illness, our dog Shelby passed away after seventeen years with us, and my father-in-law died not long after being diagnosed with a particularly vicious form of cancer.

During this time period I was keenly aware that my daughter, who recently turned five, was experiencing these kinds of awful realities for the very first time. Death and illness loomed large in the background of her crayon-coloured regular kid life, whether because her dad was back and forth from his own parent’s bedside, or because she was sitting quietly through eulogies at funerals, or because, in the case of our dog, she was actually being asked to say goodbye before one last visit to the vet.

My daughter was now old enough to understand some of the more painful realities of life, empathetic enough to see that the adults around her were sad. She could certainly feel the absence of two much-loved grandparents and one once ever-present canine companion. And while we grappled with our own impossible adult grief, and with the endless grown-up details of death, we also had to carefully navigate talking to her about what it means when we lose someone we love. It seemed there was no handy manual to explain to a child why we die, or to tell them what happens or where we go when we do.

While I was fumbling around, fielding my child’s very smart questions and offering my own clumsy explanations, a friend suggested I reframe the conversation. “I tell my kids that people live on in our memories,” she said. “We can tell stories about them. Celebrate their birthdays. Look at photos and belongings.” For us that meant treasuring Grandma’s vibrant purple scarf, or Grandpa’s favourite leather gloves. It meant looking at the dog’s old toys or finding a special place for her collar. It meant cutting out pink and red paper hearts with their names on them and taping them up on her bedroom wall.

It also, of course, meant books—and lots of them. Books that helped explore what we were feeling and books that suggested ways that we could cope. I went on a hunt for guides on the impossible task of parenting through grief, but I also went looking for children’s picture books that offered age appropriate explanations of why, as my daughter articulated it, “people were no longer in the world.” We read Invisible String by Patrice Karst and Joanne Lew-Vriethoff, a book that suggests we are always connected to those we love and that “no one is ever alone.” We read Goodbye Mog by Judith Kerr, which described a family pet as going “up and up and up and up right into the sun.” (A description my daughter particularly liked that we now use regularly.)

But perhaps the children’s book that most resonated was Carey Sookocheff’s The Remembering Stone, one that echoed my friend’s very wise recommendation to reframe the conversation.

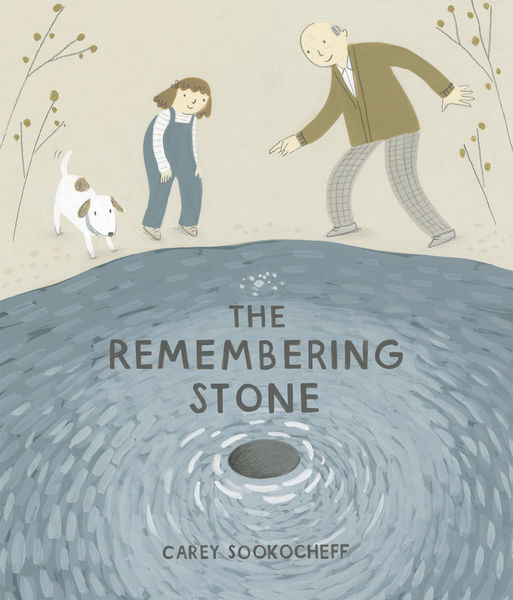

The Remembering Stone has been described in reviews as a “quiet” story, an apt observation given how beautifully sparse it is. The book’s generous breathing room pairs well with the difficult subject matter at hand—a delicate and thoughtful exploration of how children can cope with grief.

The Remembering Stone is the simple tale of Alice, a young girl who treasures the stone her grandfather once gave her—so much so that she brings it to school for Show and Share to talk to her classmates about it.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

“It looked just like a regular store, but Alice knew it was different,”

While the other children show off new boots and a book about dinosaurs, Alice opens her palm to reveal the flat, round stone—maybe not as impressive as the other objects, but certainly special nonetheless.

“It was how..Alice remembered her grandpa.”

The book then gives the reader a touching recollection of the pair attempting to skip stones together—zip, zip, zip!—and even though Alice is unsuccessful, she hangs on to one perfect stone in the hopes that she’ll be able to get the hang of it next time.

“But next time never came.”

What is most admirable about The Remembering Stone is it doesn’t hide its message in euphemisms but instead speaks directly and honestly to children about death. It explores how we can can lean on others for support and care, while finding healing in chosen objects and rituals. It lets us know that as time passes, we can reach for these things to help us feel more connected to what is gone.

Things like grandma’s scarf, grandpa’s gloves, and pink and red paper hearts taped to the wall.

A few months ago, while my daughter was at school, she suddenly became overwhelmed by feelings of missing the dog. By then Shelby had been gone for about seven months, but anyone who has experienced grief knows it has no reliable timeline, that a feeling of lack can derail you at any time. For my daughter that feeling crept up on her in the middle of her classroom, and she let the people around her know.

Seeing she was upset, a few of her friends came together to draw pictures and make cards, some of which offered depictions of our beloved family pet. When she arrived home that day her pink backpack was stuffed with carefully scrawled condolences care of her kindergarten class.

At the end of The Remembering Stone Alice ends up with a pocket full of stones from her friends, each one reminding her how they tried to help when she was sad. This conclusion underscores the reality of grief—that despite how impossible it feels, there are still things we can hold onto, and people who will help us through the hurt. It’s a message that I have been grateful for, both for my daughter and myself.

Book Therapy is a monthly column about how books have the capacity to help, heal, and change our lives for the better.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Stacey May Fowles is an award-winning journalist, novelist, and essayist whose bylines include The Globe and Mail, The National Post, BuzzFeed, Elle, Toronto Life, The Walrus, Vice, Hazlitt, Quill and Quire, and others. She is the author of the bestselling non-fiction collection Baseball Life Advice (McClelland and Stewart), and the co-editor of the recent anthology Whatever Gets You Through (Greystone).