Sorry Not Sorry: On Writing a Good Apology

By Alicia Elliott

To some extent, public apologies always are a little false. We’ve had no shortage of them recently. Harvey Weinstein, Kevin Spacey and Louis C.K. come to mind. Their statements always feel removed from the situations or behaviours they’re apologizing for, forgoing the words “I’m sorry for my behaviour” and instead relying on implied apology with words like “I regret” or the responsibility-dodging phrase “I am sorry for the feelings [my victim] describes having.” Perhaps part of the reason they’re such terrible apologies is that they’re written to appease the public – not the person or people this person actually hurt.

In this way, when Aziz Ansari apologized via text message to a woman he dated known as “Grace,” he was being more authentic than any of the men who have issued public apologies. When Ansari wrote his apology – as far as he knew – Grace was the only one who would ever read it. He didn’t know it would be read and analyzed by thousands of people on the internet, or the subject of so many thinkpieces.

But these other men – Harvey Weinstein, Kevin Spacey, Louis C.K. and countless others – did know. In fact, they were only “apologizing” because news coverage forced them to. Once allegations were made unavoidably public, the only choice they had was to address them. How much can a person mean an apology like that? Are they actually apologizing for their behaviour, or are they apologizing for being caught? Do they care about how they hurt their victims, or do they only care that the public cares that they hurt their victims?

In terms of apologies, Aziz Ansari’s text apology was actually pretty good. He didn’t question Grace’s experience or blame her; he didn’t attempt to defend himself. He acknowledged that, even though he didn’t mean to, he had hurt Grace, and he apologized. “Clearly, I misread things in the moment and I’m truly sorry.”

It’s obvious that Ansari’s apology wasn’t enough to make Grace feel okay about everything, since she ended up going public about her experience with him. That’s okay. She’s under no obligation to accept his apology. No one is under any obligation to accept anyone’s apology. It’s strange that as a society we think that words alone could ever be enough to wipe away the emotional, physical, intellectual and sometimes financial impacts of a traumatic experience. We have to live with that pain forever, while the person who hurt us gets to offload their guilt by uttering two small words? Seems pretty bullshit to me.

And yet holding a grudge takes so much energy. It often becomes toxic, taking away from our ability to enjoy the best parts of our lives. In those cases, forgiving a person can be less painful than stoking the fire of your rage. After all, putting a fire out is exponentially less work than keeping it burning forever.

That’s something that I think often gets missed in these discussions: victims want to put out their fires. They want to stop burning. They want to move on with their lives and feel joy again. But this is hard to do when the person who hurt them doesn’t apologize, doesn’t ask for forgiveness, doesn’t even understand why or how what they did was wrong. Sometimes that last part hurts even more than what the abuser originally did. How can this person deny that they hurt you? How can they deny the harm they’ve caused when the evidence is right in front of them?

Bad apologies always put an unfair burden on the victim. When your apology is, essentially, saying, “I’m telling you I regret this, so you should be thankful. Forgive me already,” you conveniently ignore the fact that your victim has no reason to trust you and every reason to doubt you. After all, you’ve already hurt them. Why should they believe you’re different now?

Good apologies, on the other hand, put the burden on the person who caused harm. If you’re truly sorry for what you’ve done, and genuinely want to help your victim move on from the pain you’ve caused, you need to make yourself vulnerable. You need to acknowledge uncomfortable truths about yourself. You need to show that you’ve thought about your behaviour, analyzed what you did and why you did it, and come out understanding why and how it was wrong. You need to show that you now have the self-awareness to make sure, as much as possible, that you won’t do it again. You need to acknowledge the pain you’ve caused. You need to say you’re sorry.

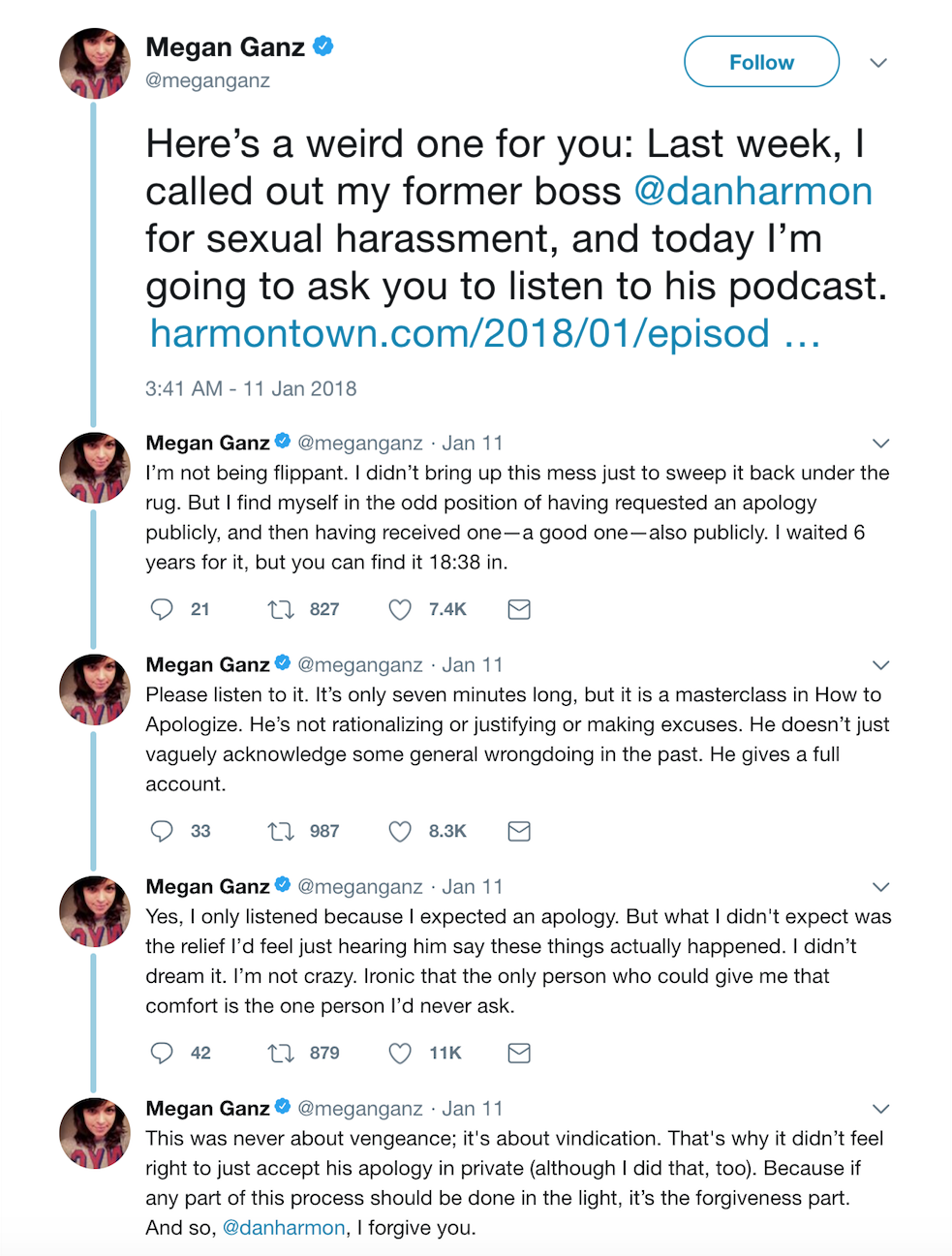

Perhaps this is why writer Megan Ganz publicly accepted Dan Harmon’s apology. Ganz was a writer on Harmon’s TV show Community. She said his inappropriate behaviour toward her made her doubt her talents as a writer, impacted her trust of male bosses, even tainted her feelings for the first TV episode she ever wrote. Harmon engaged with her directly over Twitter, then addressed things in his podcast, Harmontown. Ganz’s response?

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

As Ganz articulates so concisely, one of the main reasons apologies can be helpful to a victim is that they validate the very feelings their abuser wanted them to deny or ignore. “I didn’t dream it. I’m not crazy. Ironic that the only person who could give me that comfort is the one person I’d never ask.”

In CanLit there have been many public outings of alleged abuse and inappropriate behaviour these days. Starting with Steven Galloway’s now-infamous firing at UBC, moving into the creation of the UBC Accountable letter. It's singular focus on Galloway's life and reputation very publicly worked to create sympathy for Galloway. If this was about due process and UBC, the fact that signatories did not meaningfully engage with the complainants in this case, or ask them how they could support them, made it clear that their "Procedural fairness for all" claims were not backed up by any significant actions. In fact, as the resulting op-eds in the press and discussions on social media made clear, this privileging of Galloway's perspective ultimately worked to sow doubt around the veracity of the complainants’ numerous accusations.

Whatever its proposed intention, the most harmful effect the UBC Accountable letter has had has been inadvertently encouraging women to silently endure abuse – as long as it's at the hands of a well-respected writer. That's certainly how I perceived it when I first read it. The pushback the letter has received since - from the complainants, UBC students, sexual assault survivors, advocates and activists - shows I'm not alone in that reading. Most signatories still refuse to apologize for this effect, and many still refuse to acknowledge the pain they’ve caused, whether they meant to or not.

PEN Canada has decided to support UBC Accountable’s letter. While they acknowledged the “chill” this letter caused, how it could intimidate writers, how it could keep them from coming forward about abuse, PEN Canada somehow missed the irony that throwing their institutional weight behind supporting this document could create the exact same “chill” they described. Their statement could intimidate writers; their statement could keep victims from coming forward about abuse. And though they acknowledge “not all speech is accorded equal weight,” their statement gives considerable weight to the speech of UBC Accountable signatories. After all, not all of us are powerful enough to have PEN Canada deem our hurtful words be kept online as “a permanently accessible digital record.” PEN Canada has not apologized for this.

Then there was Mike Spry’s recent blog post confirming decades of rumours about the toxic environment of Concordia’s Creative Writing program. While his words finally validated what Emma Healey wrote in her brilliant 2014 Hairpin piece, “Stories Like Passwords,” and validated the stories so many women from Concordia shared, Spry still did not apologize. Not in his essay, at least. Hopefully he has apologized privately to those he’s hurt and silenced.

There are allegations of abuse against poet and former Coach House poetry editor Jeramy Dodds, reported upon recently in The Globe and Mail. Since an apology is also an admission of guilt, I don't expect any apologies from Dodds will be forthcoming.

And let’s not forget Angie Abdou, author of the recent novel, In Case I Go. Abdou wrote about her consultation process with the Ktunaxa Nation in a Quill and Quire article originally (and insensitively) titled “Getting to Yes.” She both misrepresented the nation’s support of the book, and published her article about the process without asking the Ktunaxa nation for permission to do so (an author's note was added by Abdou, apologizing for the "incorrect wording" in the essay). When they wrote a response clarifying this, Jonathan Kay came to Abdou’s rescue with a negative piece on the Ktunaxa Nation Council and, specifically, Troy Sebastian, who penned the statement on behalf of the council. Abdou may have apologized for her original article, but she did not apologize to the Ktunaxa Nation Council for letting Kay exploit her story for his own agenda. She also did not apologize to the Ktunaxa Nation Council for asking Quill and Quire to suppress the publishing of their statement, a request acknowledged in Kay's article defending Abdou and her work.

Instead, she struck up an alliance with Kay that culminated in his tweeting out a screenshot of professor Erin Wunker’s personal Facebook page to his followers. Like good little foot soldiers, they harassed Wunker. Abdou reacted to this by apologizing to Christian Bök, who was initially blamed for leaking the photo. To be clear, Bök did leak the photo, but to Abdou, not Kay. A series of events Abdou describes in a Facebook post explaining these actions. According to a recent Globe and Mail article, both Bök and Abdou have apologized to Wunker for their role in these events. If we hold our breaths for Kay to apologize for anything, ever, we may all die.

I don’t think any of these people are necessarily irredeemable, or unable to recognize their mistakes and change. But the first step towards redeeming yourself is acknowledging the pain you’ve caused and apologizing for it. It’s hard to come to terms with a mistake you’ve made, particularly when it had ramifications you never could have imagined. But if you don’t, you’re only prolonging that pain.

If any of these people do attempt to apologize to those they’ve hurt – or, in cases which involve criminal activity that hasn't been proven in court, people they’ve allegedly hurt – I hope that they can make their apologies less about themselves and more about the impact of their (alleged) actions. I hope that they offer the sort of comfort that Ganz describes feeling when she received her apology from Harmon. The kind of comfort only they can give.

Mostly, though, I hope that these people can examine their complicity in a system that not only allows, but encourages these types of abuse, particularly against marginalized people – that is, a system that allows and encourages abuse so long as those exercising their power and causing pain have the good sense to be quiet about it. Because there would be no such thing as “open secrets” if we didn’t already know abuse was happening and stayed quiet about it. There wouldn’t need to be national apologies for cultural genocide if nations weren’t allowed to rationalize that genocide and keep key information about it from the public. When so many of us are in so many ways complicit, how do we, collectively, apologize for that? How do we recognize what we’ve done, the impact it has had, and move forward? How do we offer comfort?

These are questions we all must answer for ourselves.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Alicia Elliott is a Tuscarora writer living in Brantford, Ontario with her husband and daughter. Her literary writing has been published by The Malahat Review, Room, Grain and The New Quarterly, and her current events editorials have been published by CBC, Globe and Mail, Maclean's and Maisonneuve. She's currently Associate Nonfiction Editor at Little Fiction | Big Truths, and a consulting editor with The New Quarterly. Most recently, her essay, "A Mind Spread Out on the Ground" won a National Magazine Award.