A Great Kids' Book is "a Kind of Graffiti": Sara Cassidy on Why Wonder, Not Instruction, is at the Centre of Her Writing

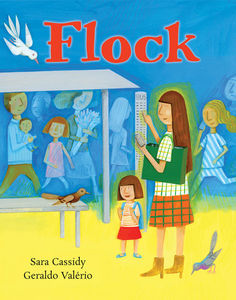

A little girl tosses a snack to some birds at a bus stop. It's a small gesture, but in Sara Cassidy's Flock (Groundwood Books, illustrated by Geraldo Valério), it becomes the jumping off point for a fantastical adventure, where more, and more, and still more birds appear to join in an impromptu urban feast.

Joyful, wild, and outlandish in the best way, Flock mixes a parent's understandable preoccupation with a child's ability to see the wonder in the everyday, and filters the results through Geraldo Valério's delightful artwork that grounds the birds as the stars of the show. When owls, turkeys, and increasingly unusual birds appear, the little girl grants them names and welcomes them, letting the adults around her in on a surreal magic they could have easily missed.

We're speaking with Sara today as part of our Kids Club series for children's literature writers. She tells us how a moment of vacation freedom created the room to observe the real-life scene that inspired Flock, why a "good children’s book does not 'hand down' knowledge", and the most joyful parts of the writing process for her, including what she loves about working with editors.

Open Book:

Tell us about your new book and how it came to be.

Sara Cassidy:

I was at Spadina Loop in Toronto, waiting for a bus, just like the wee heroine of Flock. All around, pigeons bobbed and pecked for bugs and crumbs. One found a crust. Was it from a commuter’s rushed breakfast or packed lunch? Was it offered, dropped, or nabbed? I was on holiday, so was free to wonder and stare. One pigeon strutted, black and white feathers like a tuxedo. Another looked as though she had been salted. One pigeon was slow, another quick. And so it began, this story of young Mika who inadvertently gives away her entire snack to an increasingly rambunctious group of birds.

OB:

Is there a message you hope kids might take away from reading your book?

SC:

The solace in experiencing the smallest variations of things. The risks and rewards of being open to the new and unexpected. To allow ourselves to be chosen and celebrated by the wild, which will always rise up.

OB:

What was the strangest or most memorable moment or experience during the writing process for you?

SC:

There are three: the first, when I told my sister that I wanted to write about a train of ten distinct pigeons eating a child’s entire snack. And my sister gently advising that “feeding pigeons will not be enough.” Two, I have tried for years to write a counting book, but one after the other has been rejected, or had to morph – this book originally featured ten birds, but now it’s a haphazard 7 or so. (I could likely write a counting book of my rejected counting books!) Three, when the amazing illustrator Geraldo Valerio sent a note the day of our first review (a good one!) to say hello. Illustrator and writer generally do not meet during the publishing process. I may have written the book, but Geraldo made it.

OB:

Do you feel like there are many misconceptions about writing for young people? What do you wish people knew about what you do?

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

SC:

It surprises me that the misconception endures that children’s books must be instructive. I believe it’s a hangover from the first children’s books, often veiled pious lessons, or not-so-veiled. The books where the writer gets clubby with kids, often at adults’ expense (often these are scatological), are perhaps meant as antidotes, but ultimately do the same thing—underestimate children’s inner lives, and their nuanced abilities to observe and absorb, and interpret the world.

Writing for children is odd because, unlike books for adults, the writer is very different from the reader. A good children’s book does not “hand down” knowledge but is rather a kind of graffiti, a message across generations—a pssst, this is what I’ve learned over here (or this is what makes me laugh) – as long as the writer is honest with themselves that anything they know is as open to debate as anything they have ever known.

OB:

What’s your favourite part in the life cycle of a book? The inspiration, writing the first draft, revision, the editorial relationship, promotion and discussing the book, or something else altogether?

SC:

You have listed all my favourite parts! The initial rush of inspiration – the This! Then the writing and problem-solving – how to tether the idea as lightly as possible. I love revision, because the house is secured; now it’s only a matter of moving furniture, choosing paint colours, punching out windows. The day I get an email from a managing editor out of the blue – "are you free to talk this afternoon? I have good news" – a manuscript is accepted – is probably my favourite of all: the story will have a place in the world. Working with editors is a joy. They can see the work from the outside. They see the gaps, the inconsistencies, and help make the work whole, viable, and inviting.

OB:

What are you working on now?

SC:

I am working on two books for 7- to 9-year-olds. Before Flowers is my first nonfiction book, about the natural world at children’s fingertips. And Plums on Strings is a collection of poems drawn from 20 years in one house raising three children, about a neighbourhood’s characters and secret places and childhood’s mysteries and joys.

______________________________________________________

Sara Cassidy is a journalist, editor and the author of fourteen children’s books. Her books have been selected for the Junior Library Guild and as finalists for the Chocolate Lily Award, the Bolen Books Children’s Book Prize, the Rocky Mountain Book Award, the Diamond Willow Award, the Ruth and Sylvia Schwartz Children’s Book Award, the Manitoba Young Readers’ Choice Award and the Silver Birch Express Award. She has won a National Magazine Award (Gold). Sara lives in Victoria, British Columbia.