David Goutor on Mining Family History to Write an Extraordinary Winnipeg Man's Fight Against Fascism

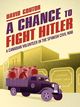

In 1936, a German man living in Winnipeg was following the inexorable march of Franco's armies towards Madrid. Hans Ibing recognized the significance of the Spanish Civil War in the struggle against the riding tide of fascism, and joined the International Brigades in order to defend the Spanish Republic. He considered it his "chance to fight Hitler"; hence the titles of David Goutor's A Chance to Fight Hitler: A Canadian Volunteer in the Spanish Civil War (Between the Lines Books).

Goutor draws on interviews, personal papers of Ibing's, and archival research to paint a picture of a man whose extraordinary understanding of the insidious roots of fascism led him to fight for what he believed in. Exploring immigration, politics, and the plight of an ordinary person rising to the occasion in extraordinary times, it's a fascinating read for those interested in military and social history.

We're pleased to welcome David to Open Book today to tell us about Ibing's unique history as part of our Lucky Seven series. He tells us about his family connection to Ibing, explains why it is important to study beyond only the leaders of political and military movements, and offers his advice for getting through the tough times in the writing process.

Open Book:

Tell us about your new book and how it came to be. What made you passionate about the subject matter you're exploring?

David Goutor:

I have a very strong personal connection to A Chance to Fight Hitler, as it is a biography of my wife’s grandfather, Hans Ibing. I knew him for many years from when we started dating in the mid-1990s until he died in 2009 (at age 100). We recognized early on that his life story spoke to many of my interests: I am a historian of immigration, labour and the left, and he migrated to Canada from Germany in 1930, became a Communist in the mid-1930s and then volunteered for to fight in the Spanish Civil War. The project developed slowly, in fits and starts, for years after that.

OB:

Is there a question that is central to your book? And if so, is it the same question you were thinking about when you started writing or did it change during the writing process?

DG:

Hans Ibing always saw himself as just an average person, yet he lived an extraordinary life. As I researched and wrote the book, I appreciated just how extraordinary it was to have grown up in Germany during World War I and the 1920s, to struggle to hold a job in the early 1930s, or to join the International Brigades in Spain. I also changed the focus to not just how he survived these times, but tried to help change them, carefully considering at key moments what was the right thing to do. It is not just leaders and elites who make these decisions, rank-and-file workers and volunteers do too.

OB:

What was your research process like for this book? Did you encounter anything unexpected while you were researching?

DG:

Ibing was someone who did not live in the past. He always looked forward and especially focused on enjoying the better times (with a good job and starting a family) in the latter part of the twentieth century, rather than the upheaval of his younger life. That’s one reason why it took a long time for me to commit to writing his story, and then to gather material. It was a process of finding the interviews he had done (with other scholars of the Canadian volunteers), recalling some stories he did relate at the family dinner table, and drawing on the historical scholarship to piece the book together. The process brought surprisingly few surprises – his memories were quite clear on most things – but I was struck by the toll the memories of the war took on him. He drove a truck during the war and thus saw first-hand the bombing of civilian targets, and the suffering of the Spanish people in general.

OB:

What do you need in order to write – in terms of space, food, rituals, writing instruments?

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

DG:

I am a pacer, so I need lots of space so I can pace about while I am working through my thoughts (I am the same in lecturing, too). I am also a night owl, though now I have young children so writing this book forced me to change my habits – or just accept being tired much of the time. I discovered that being very tired can often make writing easier – though I would not recommend adopting it as a method.

OB:

What do you do if you're feeling discouraged during the writing process? Do you have a method of coping with the difficult points in your projects?

DG:

I always tell my students that the best remedy for troubles with writing is to get reading. Find books that engage and inspire you – not books that you think you should like, but ones that make you appreciate the value of good writing. Keep those around and re-read them when you are struggling. In writing this book, I never had to look far for inspiration, as there are so many great books about Germany after World War I, the history of the Canadian and international left, and the Spanish Civil War.

OB:

What defines a great work of non-fiction, in your opinion? Tell us about one or two books you consider to be truly great books.

DG:

Great historical non-fiction draws a picture of people in a different time and place but does so in a way that contemporary readers can understand. It makes you appreciate that we live not in an atomized, separate present, but in one historical moment that is deeply connected to a rich and complicated past.

Two great examples are Ian McKay’s classic study of early socialism in Canada, Reasoning Otherwise, and Paul Preston’s The Spanish Civil War.

OB:

What are you working on now?

DG:

I am juggling a few projects, but my main ambition stems from new courses I have developed at McMaster on technology and the future of work. I want to put the current panic about robots and artificial intelligence replacing humans into historical context. This is not the first time that technology has transformed work – either paid labour or household work – but the story of how workers, social movements and governments responded has been largely forgotten. People often say “this time it’s different” regarding technology in the 21st century – but they show little knowledge about what actually happened the previous times.

______________________________

David Goutor is assistant professor in the School of Labour Studies, McMaster University. He researches and teaches about working-class formation, union and leftist movements, immigration, and transnational migratory labour systems.