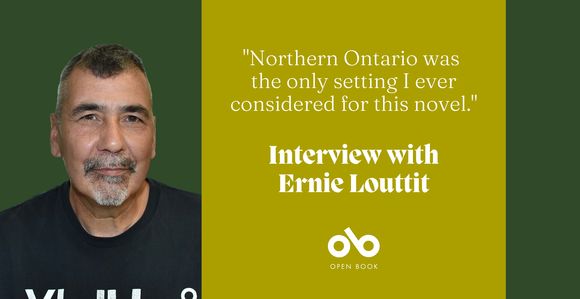

Ernie Louttit's Debut Novel Follows an Indigenous WWII Veteran's Battle Against Corruption and Prejudice in Northern Ontario

Elmer Wabason and Gilbert Bertrand share a deep bond when they return to their small northern Ontario town after the brutalities of fighting in the Second World War. They're both trying to rebuild their lives, forget the violence, and maintain their friendship. But what didn't matter in the trenches—namely the fact that Elmer is a Cree man and Gilbert is white—is suddenly, deeply relevant to many of the people around them.

Ernie Louttit's Pine Bugs and .303s (Latitude 46 Publishing) is a story of people coming together in the face of injustice, of love between families and friends, and of resistance against bigotry, corruption, and deception. Tightly plotted and deeply rooted in its historical setting, it showcases the skill Louttit, a veteran and retired police officer, built in his three previous nonfiction books. His pivot to fiction demonstrates powerful insight into the human mind and the resilience of the spirit.

We spoke with him about Pine Bugs and .303s as part of our Long Story interview series, discussing his writing process and the book's inception. He told us about how imagining what life might have been like for his grandfather—had he survived the Second World War—sparked the idea for the novel; about an actual, physical piece of history he found as a child that sharply illustrated the prejudice against Indigenous people in Canada; and about the unexpected, visceral difficulty that came with having to kill off a character while writing.

Open Book:

Do you remember how your first started this novel or the very first bit of writing you did for it?

Ernie Louttit:

I was on a train traveling from Saskatoon to Oba, Ontario, a little hamlet 600 miles north of Toronto where I grew up. The train pulled into siding to let a west bound freight train pass. If you are in a hurry, don’t take the train. As I looked out the window at the rocks and trees of the Canadian shield, I thought about my grandfather who was killed in World War 2. I wondered what his journey would have been like if he survived. What would have awaited him? What would our family be like if he had been part of it? I always have a notebook with me, because you never know when an idea will come to you. I wrote the first few lines of the book and the story flowed from there.

OB:

How did you choose the setting of your novel? What connection, if any, did you have to the setting when you began writing?

EL:

I chose to set the book in Northern Ontario because of my experiences growing up there. I went to a one-room school until grade eight then went to a community north of Oba for high school. I quit school at 15, and worked on the railway until I joined the army at 17. I worked all over Northern Ontario, and I always felt a deep connection with its small towns, villages, and the land. Small towns physically reflected several generations of change. Like a standing water tower for steam trains remaining next to a modern railway station, for example. The same could be true in a city; however, in a small town the contrast between modern and old is part of the fabric of the community. I hoped readers from Northern Ontario would find Pine Bugs and .303s comfortable and familiar, and readers elsewhere would experience the unique features of this beautiful part of Canada. Coal oil lamps for light, wood stoves for heat, and bitter winters sound unbelievable in this day and age, but it was a reality for me in the late 60s and early 70s. Northern Ontario was the only setting I ever considered for this novel.

OB:

Did you find yourself having a "favourite" amongst your characters? If so, who was it and why?

EL:

Without a doubt, Elmer Wabason was my favourite character in the novel. Elmer drove the story from the start. He is an intelligent, stoic man who loves his family, and had his life transformed by the war. If he were a real person, we would all owe him debt and gratitude: He could have avoided service and stayed with his children, but he volunteered to fight for a country that did not consider him a full citizen. He had no time or tolerance for racists, thieves, or cowards. Elmer had his flaws: He was sometimes naïve and too trusting, but he recognized his weaknesses and surrounded himself with good people. Elmer does the right things for the right reasons in the face of danger, and this is what made him my favourite.

OB:

Did you do any specific research for this novel? Tell us a bit about that process.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

EL:

I did research on the grievances of First Nations veterans while writing Pine Bugs and .303s. From stories I heard over the years and my own experience, I knew some of the inequalities and outright racism First Nations people faced. When I was 10, I found a rusty metal sign in the shed behind the old hotel in Oba. The sign said something to the affect that Indians were prohibited by law to enter. It used to be on the door of the hotel, prior to 1951. I wish I kept it, as it told me a lot of about what was acceptable in the past. First Nations veterans had legitimate grievances after World War One and Two, and as recently as the Korean war, so I fact checked the details for the book. For example, the loss of treaty status if a First Nations person was overseas for more than four years.

OB:

What was the strangest or most memorable moment or experience during the writing process for you?

EL:

I killed a character and immediately regretted it, even though I knew I was going to do it. I got up and paced around. I stared out the window and had to make peace with myself before I carried on writing. I reminded myself it was a novel and the character was fictional. It was an unexpected feeling, and the strangest moment while writing this book.

OB:

Who did you dedicate your novel to, and why?

EL:

The novel was dedicated to our first grandson, Adler. I hope that when he is old enough to read Pine Bugs and .303s, the book will spark an interest in the history of our country, and a respect for veterans. In twenty years our most recent veterans from Afghanistan will be middle aged, and they will need young Canadians like Adler to remember their sacrifices. I hope he is a just and fair-minded person who will not tolerate injustice, and speak against it if need be.

OB:

What if, anything, did you learn from writing this novel?

EL:

For someone who lived a chaotic, and often violent, life anchored by the process and self-discipline of the police and military for 35 years, I had lot of fun writing this novel. I explored feelings and thoughts I had never considered about the past. It may distract some writers, but I wrote most of Pine Bugs and .303s with music blaring, family members interrupting for rides or store runs, and sometimes I wrote in only 5- or 10-minute sessions. Writing fiction felt liberating. I wanted to tell a good story that resonated with anyone who read it. Our country has changed a lot during my lifetime, and I am old enough to appreciate those incremental changes that are sometimes lost on younger people. I do not take anything for granted, and I won't apologize for having fun writing this book. The biggest lesson I have learned is that I love to write, and I feel honoured to be read.

_______________________________________________________

Ernie Louttit is a retired soldier and police officer, and has written three books, Indian Ernie: Perspectives on Leadership and Policing, More Indian Ernie, Insights from the Streets, and The Unexpected Cop: Indian Ernie on a Life of Leadership. Winner of the Saskatchewan Book Award in 2014 and the Reveal Indigenous Arts Award in 2017. Pine Bugs and .303s is his debut novel. He lives in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan.