"I Saw That Language Could Break and Be Reassembled" Prathna Lor on Early Reading & Their Poetry Debut

A debut collection of poetry is always something exciting; a chance to inhabit a new perspective, a new way of processing and experiencing the world, while getting those great literary shivers over a spectacular line here and image there.

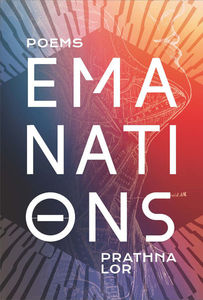

And every once in a while that portal becomes something truly special, a glimpse of a mind at work with vitality and true creativity. And so we're excited to speak to Prathna Lor today, the author of Emanations (Wolsak & Wynn). Emanations, Lor's first full length collection, has been called "luminous" and "inspiringly bold", charged with "a radical philosophy of being" (David Chariandy).

Lor's assured, electric use of language and exhortation often becomes a kind of rallying cry to wonder. Very much the collection we need right now, it's a grounded, determinedly hopeful collection that is equal parts clear eyed and intent on resisting a reductive, consumerist, unequal world.

Today, we get to speak to Prathna, who serves as Poetry Editor at Shrapnel Magazine, about their early experiences with poetry and the path that led to Emanations, from the novel that, paradoxically, taught them about poetry to the

"universal glimmer" they are trying to unearth in each piece of writing.

Open Book:

What is the first poem you remember being affected by?

Prathna Lor:

This is going to be a bit of an unconventional answer but when I was a teenager and scrounging around my local library I managed to pick up by chance Virginia Woolf’s The Waves. I didn’t really have an idea of the literary or what “literature” was at that point – I just knew that there were books and some of them did things with story of some of them did not. I remember being viscerally struck by The Waves. I felt something in my gut. There was beauty and voice and although a novel I saw, for the first time, what a poem is and what it could do. It ignited an intuition I had about language – one that I would carry with me (and would carry me) through my later education. I saw that language could break and be reassembled, that consciousness could seethe and spread. And I knew that I always wanted to work with the line.

OB:

What do you do with a poem that just isn’t working?

PL:

I think the question of a poem’s labour is an interesting one – and one I don’t quite fully understand. Why must the poem work? Why must it do something for the reader? If a poem works for me, will it work for you? For me, writing is a process of removal, of sculpting. I am trying to excavate a glint, a sense, a scent – something fleeting. That is the work, at least for me. If there is tension or discomfort in the way that a poem does not sit quite right in its execution – how it lands on the page, how it gives and interrupts breath – then it needs a different angle of light, a different cadence. I think a poem is always trying to work through me and if there isn’t a sense of justice in terms of its presence on the page, I have no hesitations about discarding it and starting over. I don’t think a poem is ever truly lost in this way – it returns as another, or is scattered, if anything, as fragments, resurfacing in another form, somewhere else.

OB:

Do you write poems individually and begin assembling collections from stand-alone pieces, or do you write with a view putting together a collection from a beginning?

PL:

I feel like I am continually trying to write one poem. This is related to my process of excavation. To be clear, I don’t think there is a definitive poem I am trying to unearth; rather, there is a kind of universal glimmer that feels visceral to which I am trying to give a voice. Poetry – or language – is an account of language’s encounter with itself, to which I can bear witness however unevenly or incompletely. Whether that transpires between the reader is a different question. I’m not very good with intrigue or reality so thinking about collections – or even the unity of a poem – feels impossible to me. To that end, I have a number of lines that try to touch something universal, and it is from each line that I try to figure out how they will take shape, fracture, and come into being as part of a larger structure. At best, I try to intuit the shape a work will take.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

OB:

What’s more important in your opinion: the way a poem opens or the way it ends?

PL:

Both are trying to do something significant in different ways. I struggle the most with endings because the work feels perpetual, unfinished. I think I have them reversed in my own practice. So much of what I have been trying to do recently is to account for the barriers of everyday life that infringe upon existence. We could give them names like transphobia, racism, violence but sometimes that naming isn’t enough. In that sense, I want to move inside the critique rather than just speak it. What does it mean to live in the barrier? That’s often where I begin such that my openings can feel like impasses – which must be done delicately so as not to alienate the reader. The question is then how to give impasse an audience so that something can be witnessed? At the end of the poem, I want the cadence to resolve but there is, too, a balancing required so that its punctuation is not absolute. Each poem is a field of resonance so there isn’t so much beginnings and endings I see in my work but echoing links from one variation to another.

OB:

What is the best thing about being a poet... and what is the worst?

PL:

The amount of time I spend thinking about beauty and agony.

_______________________________________________________

Prathna Lor is a poet, essayist, editor and educator, who has published in Canadian Literature, DIAGRAM, C Magazine, Jacket2, Poetry is Dead and Plenitude Magazine, among others. Lor is Poetry Editor at Shrapnel Magazine and holds a PhD from the University of Toronto. They live in Montreal, QC.