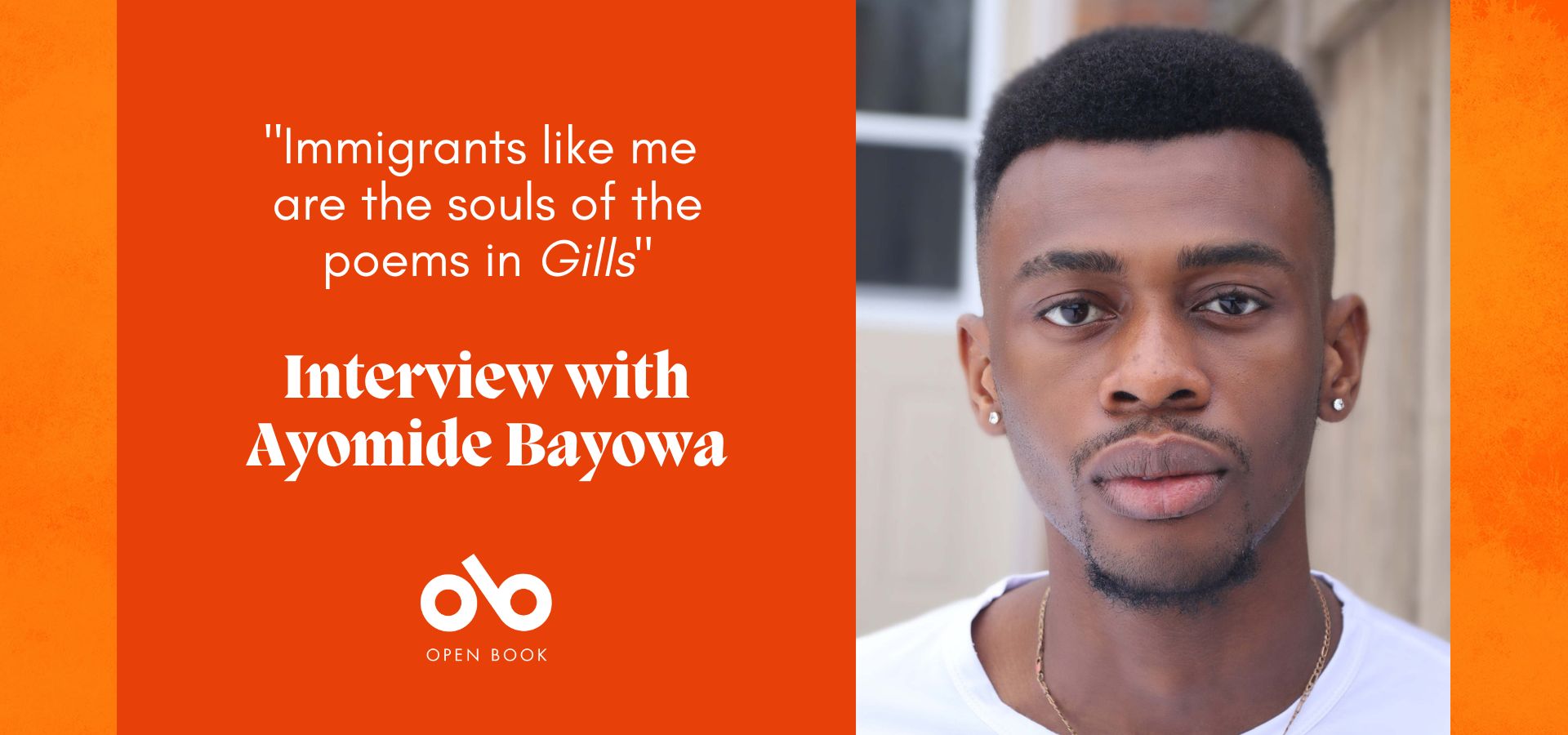

"My Poetry isn’t Mine to Define to You, My Friend" Ayomide Bayowa on His Masterful Debut Collection, Gills

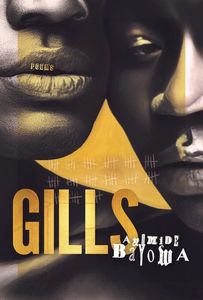

Mississauga poet laureate Ayomide Bayowa's full length debut Gills (Wolsak & Wynn) is a lyric, thoughtful exploration of the immigrant experience, the insurmountable challenges of economic inequality and a predatory debt system, and the body's ongoing, urgent quest for life. Called "piercing and prophetic", it heralds a major new talent. Bayowa's raw honesty and quiet mastery make Gills a note-worthy debut even in a season of spectacular poetic offerings.

We're excited to welcome Ayomide to Open Book today, speaking with him about Gills as part of our Line & Lyric series. He tells us about how the collection's title came to be and how the rhyming titles of the first and last poems in the collection intersect, reveals the most surprising part of working on Gills, and shares a Biblical quotation in Yoruba that informs his poetic sensibility and work ethic.

Open Book:

Tell us about this collection and how it came to be.

Ayomide Bayowa:

Gills’ earliest form of existence was from a mere creative choice of title for my the manuscript for the 2021 Cave Canem Poetry Prize submission. By then, the poems were never really meant to be associated with the title. I had earlier titled it ‘Outlanders’ Latte’ for my strong loyalty to coffee with the basis reflecting on my source of addiction to caffeine while working relentlessly at a factory, as a general labourer. I really wanted the coffee theme for the way I saw the immigrants’ world of my workplace then; as in debt to caffeine for activeness/work stress survival. But little did I know that including those of us, mere owners of bicycles would be laid off for unnecessary reasons and begin to worship the Canadian system of credit card debts, phone bills, and collections amongst others. From a random imaginative choice, Gills dawned on me when Paul, my editor, asked for another title for the manuscript.

OB:

Can you tell us a bit about how you chose your title? If it’s a title of one of the poems, how does that piece fit into the collection? If it’s not a poem title, how does it encapsulate the collection as a whole?

AB:

'Gills' was never the title of one of the poems until I got stuck on titling the very last poem of the book. I would say, I am one of those that query why writers name their books after a piece but here I am, naming a piece after my book to bottle/jar up my last creative act of mourning and toss it into the world’s hands. Gills would firstly invite you to think of all aquatic references fundamentally possible. 'Gills' will give the first impression of a ‘fish’ whose skin parts are its natural components for survival (breathing, locomoting, and even feeding). There, you will catch the hint of marker and our pre, present-continuous dependency of people of colour on their skins for survival or misfortune. And this, of course pairs the analogy embodying the significant role water plays for immigrants. That is, immigrants like me are the souls of the poems in Gills.

My intention is to receive readers to my literary world of western socio-economical barriers with necessary informations about staying above the water. The idiomatic expression meaning 'to rise above financial crisis/difficulties,' I believe. As for us, already bloated with loans and promises to pay tomorrow and the day after, Gills offers unmistakable transitioning via the poet personas' strained journeys. Sometimes, I woke up in the middle of the night, unable to get back to sleep, thinking of how to pay bills with payment deadlines and my final essays, fast approaching. In my to-do list, I was also to reply to my editor with some edits on some of the poems – I was like, “Wow, life’s getting me pretty good.” To my dumb surprise, I started to write a poem I title ‘Bills.’ Then I was like, “Good, Gills’ got a company.” I intentionally made ‘Bills’ the first in the book, then ‘Gills’ the last poem. Consider ‘Gills’ as a poem, an unintended wake and burial ritual for my friends Pojo and Samson Ojeniyi plus my Grandma, Veronica. I don’t want to write any more poems to mourn them literally, it’s now in y’all hands to share my sorrow. I mean, what are readers for?

OB:

What was the strangest or most surprising part of the writing process for this collection?

AB:

The fact I was actually going to be an author. What? That I was able to reply to emails and return edit corrections faster that submitting my school assignments. It all went by fast, from when Paul reached out to my professor in order to propose publishing me to now being published: that journey was one by myself and God. Because even my roommates/friends do not see me as a writer/laureate, the world sees me as they do not believe how I come up with these pieces. Most especially, they catch me writing. Yes, catch, because they believe a writer with my kinds of achievements should live in the library or be stuck to glasses and finger traces of tiny prints. But here I am, more youthful than ever. This perception of people closer to me and those from afar, help me realize that I, myself find strange how I come about certain poems. Because what will I say on days like this when I’m asked, camera-to-face, how come? My poetry isn’t mine to define to you, my friend.

OB:

Did you write poems individually and begin assembling this collection from stand-alone pieces, or did you write with a view to putting together a collection from the beginning?

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

AB:

I assembled the poems from stand-alone pieces. Only a few of them came to be in pairs or so. But poems like ‘Border Manifesto’ which became the Finalist of the Frontier Global Poetry Prize for the North America Region was written as an assignment in a Theatre Diaspora class I had one semester. More like that had been through several edits and rejections that could’ve made them not make my shortlist of poems remain in the book. So I thought, that if some could not survive the world alone, why not put them out there together, with strong hope in the power of numbers?

OB:

What's more important in your opinion: the way a poem opens or the way it ends?

AB:

In the Bible, preferably the Yoruba version, it says, “Ibere kii se onisr, afi eni ti o ba fi oriti titi de opin.” Meaning, the beginner does not matter as much as he completes the task to the end. I believe so much in the ephemerality of things in life, probably because I am a thespian and I’ve seen and acted one-too-many plays I never wanted to end but actually needed to for the manifestation of purpose. That is, I can start a poem with zero ideas of where it goes but whatever makes me add a full stop to it and begin another poem, means I found a practical way to let people in my poetic space and bottle them up in fun or thoughtful aftermaths. An intentional ending is a poet’s influential formula.

_________________________________________

Ayomide Bayowa is an award-winning Nigerian Canadian poet, actor and filmmaker. He holds a BA in Theatre and Creative Writing from the University of Toronto and is the (2021–24) poet laureate of Mississauga, Ontario, Canada. He is a top-ten gold entrant of the 9th Open Eurasian Literary Festival and Book Forum, UK, and was long-listed for both the UnSerious Collective Fellowship and 2021 Adroit Journal Poetry Prize. He won first place in the 2020 July Open Drawer Poetry Contest, the June/July 2021 edition of the bimonthly Brigitte Poirson Poetry Contest and second place in the 2021 K. Valerie Connor Poetry Contest’s Student Category. He has appeared in a long list of literary magazines, including Windsor Review, Agbowó, Ampersand Review, and more. He is the editor-in-chief of Echelon Poetry and currently reads poetry for Adroit Journal.