Playwright & Passe Muraille Artistic Director Marjorie Chan on Writing the Scenes That "Need to Get Out" First

Librettist and playwright Marjorie Chan, who serves as Artistic Director of Toronto's iconic Theatre Passe Muraille while also creating her own plays and librettos, has a knack for exploring power, identity, and connection in fascinating ways, often highlighting the experience of Chinese women, both in China and amongst the Chinese diaspora.

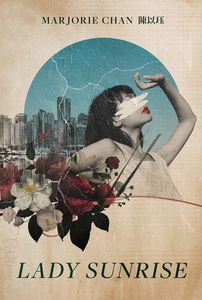

Now her gritty, absorbing play, Lady Sunrise (Playwrights Canada Press), shows the keen eye that has earned her four Dora Awards (and a whopping total of nine nominations) at its sharpest. Set against the duality of Vancouver's identity as both picturesque condo playground and desperate final rung of inequity for many, Lady Sunrise follows six women in the city's Asian Canadian community who find themselves willing to trade anything for wealth. Motivated by the freedom money buys, the need to escape abusive situations, or simply the glittering, heady allure of the astonishing riches of Vancouver's elite, the women navigate the uneasy relationship between power and money, consumerism and identity with sometimes devastating results. Raw, honest, and intense in the best way, it's a play that reminds us how essential on stage storytelling can be.

We're speaking with Marjorie today about her process, going behind the scenes of how one of Canada's most vibrant playwrights creates their work. She tells us about how she often writes the scenes with the most "heat" first, what it's like to look back and observe the themes that have emerged in her work, and how writing for opera and theatre differ and inform one another in her work.

Open Book:

Is your writing process totally page-based, or do you sometimes speak dialogue aloud (alone or with others) or try physically blocking out scenes while writing to work through things?

Marjorie Chan:

When I am writing, it is completely dependent on the project I am working on, and what I need in the moment. In general, like probably quite a few writers, I spend a lot of time ruminating, researching, talking to people before I actually am able to sit down to write. For the most part, almost 100% of my self-driven projects, I do not sit down to write until I know the final scene, or the final moment before an epilogue. The bulk of the time, I need to write that final scene or moment first. Once I get that done, then I can really start writing. I don’t always write in order, sometimes feeling for the scene with the most ‘heat’ at the moment – the one that needs to get out or whose voices are quite present. Sometimes the characters really do feel like they have voices of their own, so I let them talk even if I am not sure of the context of what they are speaking yet. Since I started as an actor, and if I have the time (!), I will read back my whole play or libretto to myself before I hand in a draft. So, it is not really a straight-forward linear approach, and is definitely influenced by writing for a performance form.

OB:

Are there themes, objects, or activities that you see cropping up repeatedly in your work that you are surprised by?

MC:

I think, while in midst of a career, I haven’t had the time to reflect back on my work and my practice as a whole. It is interesting to be in a place and a time where your own work is being studied, or part of curricula so many interesting conversations emerge with that more objective examination of my work. I would say some of the obvious things that are clear in my work, is my relationship to my Chinese culture, which is so linked with how I identify and how I move about in the world. I would say my ‘earlier’ works, Chinese history as it related to China, the country dominated my imagination. (China Doll, a nanking winter, The Madness of the Square). All are set in China, which I have of course visited, but have not spent significant time there. They are plays written in English, and come from my lens as someone whose family came from Hong Kong, and grew up deep in Scarborough. And they reflect that reality, both through challenging narratives of both how Canada views a ‘Chinese’ person and as well internalized examinations of the Chinese community itself.

In some of my work outside of traditional plays, I have had the opportunity and the curiosity to begin more explorations of diasporic Chinese. In particular, more and more I am fascinated by the early Chinese settlers of Canada, their arrivals, their means of survival, their successes. There is a great amount of material and stories that continue to captivate me, and that I am sure I will find the opportunity to dig in deeper.

Lastly, and I think Lady Sunrise falls into this category, is the contemporary lens of the Chinese diaspora in the West. I have two more plays in the works that are contemporary and wrestle with this specifically. And again, as a unique perspective from the Chinese lens, or a newcomer lens and how it sits inside of this North American culture and where it clashes.

OB:

Having written for other mediums, what (if anything) changes when you're writing for the stage?

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

MC:

The other medium that I primarily write for, is text for opera. In fact, I had an opera premiere before my first play, so my development as a librettist was concurrent with my playwriting career. However, I did find, with the success of my plays, by 2010, I had decided to place my focus on opera libretti, giving myself two years to really immerse myself in that form. I did so, because I do recognize there is a difference in approach and thinking. My practice of knowing and writing the ending first still stands, but the other part of the processes is not similar, including the form. The text is only one part of the opera, and for me, feels like it should be the spine, and be an elevation of the music. It means that there is little space for anything extraneous, or non-essential. It is writing text that will allow a composer to elaborate the experience with music. It is very different than playwriting, where I as a solo creator are responsible for creating those nuances, hitting those emotional highs and offering the texture to the world.

OB:

What do you do with a play in progress or a scene that just isn't working?

MC:

Honestly, I throw it away. Or tear it up. Or close the file and start fresh in a new window. I write fairly quickly, and I also overwrite most of the time, so I don’t have a lot of emotion over giving up something that just isn’t quite clicking. I will give it go by changing things around, or adding or subtracting characters, or improvising new dialogue. But in the end, letting it go and starting fresh usually does the trick for me. If there was dialogue or an idea that was important, it will come back. Or a new tack will be what can unlock the correct angle or approach to a work. Or having written a new draft of it, you can see the gaps better to answer what you need.

OB:

How do you see theatre and playwriting changing and evolving at this point? What excites you about those changes as an artist?

MC:

Although I do write ‘plays’ or what I call ‘play-plays’, i.e. text-based plays, I am quite active in other forms, like opera, collective works, hybrid collaborations etc. I think there are very distinct boundaries imposed on what ‘kind’ of writer once might be, but I am quite happy to take a solo role as a playwright, and then a collaborative role as a librettist, and then a facilitating writing role as a member of the collective. They all have different satisfactions, and results in very different kinds of work. I think the breaking down of those boundaries is something we will see more of. Our experiences as a society are so vast, one form can’t possibly be able to express all the differences of the human condition. The evolution of the practice of writing/theatre making is critical to a growth and a maturation of the form of theatre.

____________________________________________________

Marjorie Chan was born in Toronto to Hong Kong immigrants who arrived in the late ’60s. As a theatre and opera artist, she works variously as a writer, director, and dramaturge, as well as in the intersection of these forms and roles. Her work has been seen and performed in the United States, Scotland, Hong Kong, Russia, and across Canada. Her full-length works as a playwright include the plays The Madness of the Square, a nanking winter, Tails From the City, as well as libretti for the operas Sanctuary Song, The Lesson of Da Ji, M’dea Undone, and, most recently, The Monkiest King. Some of the companies Marjorie has directed for include Gateway Theatre, Cahoots Theatre, Native Earth Performing Arts, Theatre Passe Muraille, Obsidian Theatre, and Theatre du Pif (Hong Kong). Marjorie has been nominated for nine Dora Mavor Moore Awards and won four. She has also received the K.M. Hunter Artist Award in Theatre, the My Entertainment World Award for Best New Work, a Harold Award, as well as the George Luscombe Mentorship Award. Other notable nominations include the John Hirsch Director’s Award, the Governor General’s Literary Award for her playwriting debut, China Doll, and the Canadian Citizen Award for her work with Crossing Gibraltar, Cahoots Theatre’s program for newcomers. She is also Artistic Director of Theatre Passe Muraille in Toronto.