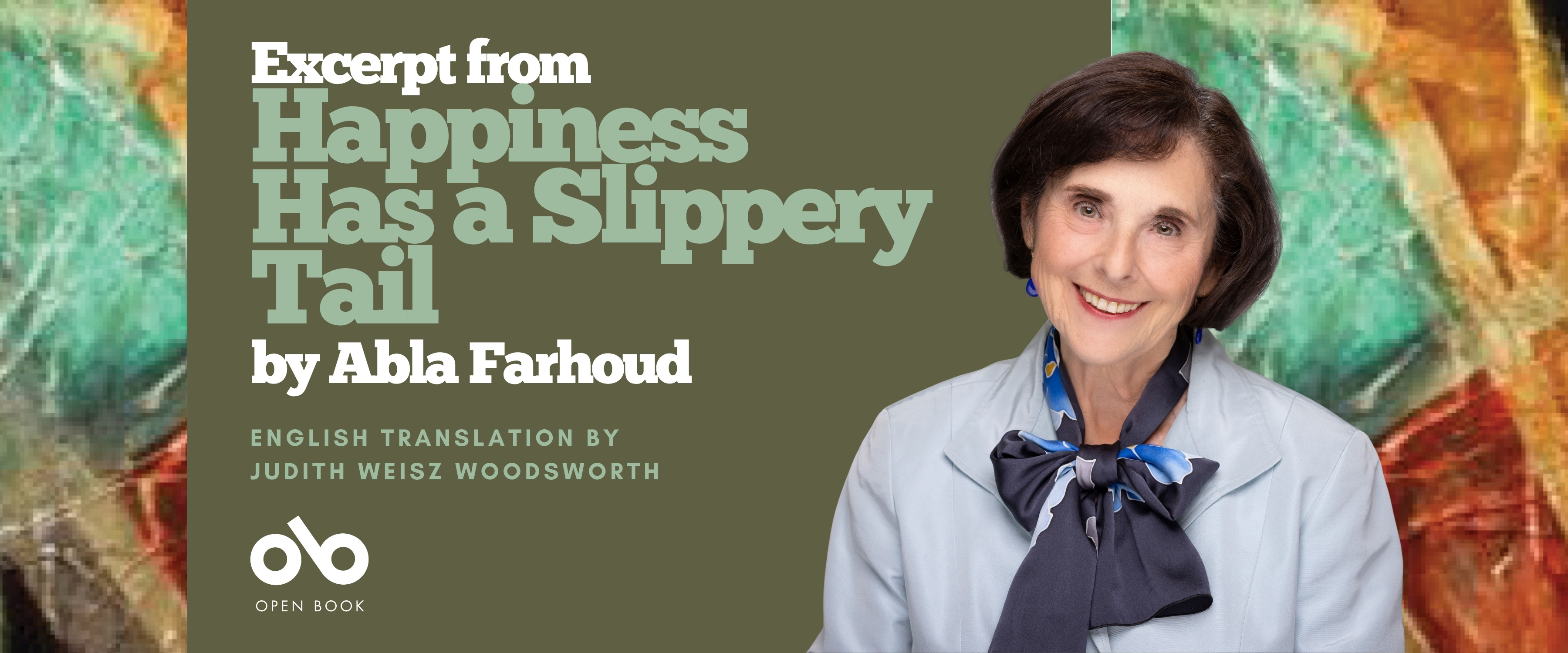

Read an Excerpt from HAPPINESS HAS A SLIPPERY TAIL by Abla Farhoud (translated by Judith Weisz Woodsworth)

In Happiness Has a Slippery Tail, celebrated Lebanese-Canadian writer Abla Farhoud offers a moving portrait of migration, memory, and resilience through the unforgettable voice of Dounia, a seventy-five-year-old mother and grandmother who has crossed borders and languages in search of belonging.

Told through Dounia’s eyes, the novel captures the ache of exile and the beauty of endurance. Unable to read or write and speaking only Arabic, Dounia nevertheless sees the world with profound wisdom. Her life unfolds through Lebanese sayings, tender humour, and fierce love as she builds a home in Montreal, declaring, “My home is where my grandchildren are.”

First published in French as Le bonheur a la queue glissante—winner of the France-Québec Philippe-Rossillon Prize—this debut novel announced Farhoud as one of Quebec’s most distinctive literary voices. An acclaimed playwright and actor as well as a novelist, Farhoud continued to explore identity, loss, and belonging throughout her career until her passing in 2021.This edition of the novel has been expertly translated into the English by Judith Weisz Woodsworth.

Check out a sample of this enthralling novel right here!

Excerpt from Happiness Has a Slippery Tail by Abla Farhoud, translated by Judith Weisz Woodsworth:

I said to my children, “When I can no longer look after myself, when that day comes, you must put me in a nursing home.”

They replied, “No, no, no. You are our mother, and we will take care of you.”

As you grow old, resignation and wisdom are never far apart. And so, I said, “When a baby is born, you lay it in a crib and wait for it to grow up; when the elderly get too old, you put them in a home with rails around their beds and wait for them to die. Each country has its own customs, there’s nothing wrong with that; the end result is the same. It’s the cycle of life. I have lived the life I was meant to live, and I will die in peace without bothering anyone … A self-sufficient peasant is an unsuspecting sultan.”

The words that spilled out of my mouth were clear and orderly, with only the slightest hesitation that had become second nature to me over time. I had rarely uttered so many words at once, and I could feel the joy and excitement of a child eating an ice cream cone at the end of a long winter.

Even though my children kept on saying “no, no, no,” each in their own way, in Arabic or in French, or by some other means, like Farid, who grumbled instead of talking, I could tell that they felt relieved. My husband Salim shook his head, rolled his eyes, and sighed, as he always does when he’s irritated. He’d long since banished the word “home” from his vocabulary. When I saw him look over at me, I knew that he was annoyed with me for having opened the door to the idea. Myriam wasn’t saying anything, but she was taking it all in as she usually does. Then Abdallah, my eldest, got up and declared vehemently, “Never, Mother. We’ll never abandon you. You’ve taken care of us your entire life. I’ll take care of you.”

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

The room fell silent for a moment. Even my children’s children turned around to look at their uncle.

Every single one of us knew that Abdallah could never take care of me. When the birds of prey came to peck away at the insides of his head, when he was disoriented and dispossessed, what could my gentle Abdallah do for me when he could no longer do anything for himself?

We were at the home of Samira, my eldest daughter. She’d invited us all to dinner, to be followed by a photo session. For once, no one was missing. It has never been easy to get all of us together for a few hours—there was always someone who was sick, or travelling, or busy. Samira, the chief organizer of the family, and Kaokab, my youngest child, had often tried to gather us together to pose for a family portrait, while their father and I were still alive. In the last, and only, photo that we had, Kaokab was a baby and Samira a little girl.

That day, it was the photographer who didn’t show up, much to the chagrin of Samira, who even said that fate was against us. How can you speak about fate for something so trivial?

As I ate, I felt a bit sad. It was just a touch of sadness. Is that what made me mention the nursing home? I think old women should never be allowed to drink wine. I felt that something was coming to an end. I had the feeling it was the last time I’d be having a meal with all my loved ones gathered around me.

On the downslope of life, with or without wine, you often feel that something is coming to an end. One day, you can no longer climb stairs without losing your breath, and one day, you can’t climb them at all. One day, you can no longer sit on the floor and then get up on your own. One day, you can no longer eat the hot peppers you love so much. One day, you can’t eat anything at all without getting an upset stomach. One day, you have a tooth pulled, and then another, until you’re left with a mouth you no longer recognize. One day, you have to wipe your mouth before kissing a child. One day, you look in the mirror and see an old woman who could have been your grandmother.

If my younger self returned one day, I would like to tell it what old age has done to me …

Little pieces of yourself slip away, as noticeably as a low flame burning down. You can feel it, you can see it. Every time we try to take control of this strange body of ours, it keeps on changing and deteriorating until it’s all over. We know that we’re slowly mourning our dying selves, even before it’s time for our children to mourn for us.

Old age is nevertheless gracious enough to come step by step, day by day. Otherwise, we wouldn’t be able to accept it and tell ourselves that as long as we’re alive, as long as our children and grandchildren are alive, nothing else matters. As our body ages, the value of things changes in our mind. And that’s how it should be.

I looked at them, one after the other, but they didn’t see me, fretting as they were about the photographer who wasn’t going to come, and having quickly forgotten about the nursing home that awaited me.

Excerpts from the Foreword and Acknowledgements of Happiness Has a Slippery Tail from translator Judith Weisz Woodsworth:

Not long after Hutchison Street was published, Abla Farhoud suggested that I translate Le bonheur a la queue glissante. She was particularly fond of this book, which she said was her bestselling one.

[…]

When Abla Farhoud passed away on December 1, 2021, Quebec letters suffered a huge loss. Regarded as a central figure in what has been called écriture migrante, literature by and about immigrants, Farhoud was also hailed as a feminist who made women’s voices come to life. Above all, she was a gifted writer who addressed universal topics such as love, loneliness, death, and dying. Mainstream Quebec media were quick to react to her passing, and praise for her was glowing. She was commended for her magnificent plays and novels, as well as her skill in imparting “lessons of humanity to her very last breath.”1

1. Television anchor Claudine Bourbonnais, quoted by Mario Cloutier, “Abla Farhoud (1945–2021) : L’ultime voyage d’une humaniste en exil,” La Presse, December 4, 2021.

[…]

Many Quebec authors are well known in English Canada, and the English-speaking world in general, but Farhoud is not among them. Yet, her delicate and nuanced treatment of exile and immigration, alienation and identity, and mental health issues would surely resonate with readers across multiple communities, in Canada and beyond.

_________________________________________________

Born in Lebanon in 1945, Abla Farhoud immigrated to Canada in 1951. She later moved back to Lebanon and spent some time in France. She studied theatre at the Université du Québec à Montréal and wrote several plays. In 1998, she published her first novel, Le bonheur a la queue glissante, for which she was awarded the Prix France-Québec – Philippe Rossillon. A number of acclaimed novels followed. Abla Farhoud passed away in 2021. She is survived by her children—musician Mathieu Farhoud-Dionne, also known as Chafiik, and singer-songwriter Alecka Farhoud.

Judith Weisz Woodsworth is a translator and Distinguished Professor Emerita at Concordia University. A specialist in translation history and theory, she has published Translators through History (with Jean Delisle), the monograph Telling the Story of Translation: Writers Who Translate, and the edited volumes The Fictions of Translation and Translation and the Global City: Bridges and Gateways. She has translated novels by Pierre Nepveu, Abla Farhoud, and Felicia Mihali, and was the receipient of the 2022 Governor General’s literary award for French-English translation for History of the Jews in Quebec by Pierre Anctil. She was founding president of the Canadian Association for Translation Studies. Woodsworth holds a PhD in French literature from McGill University.