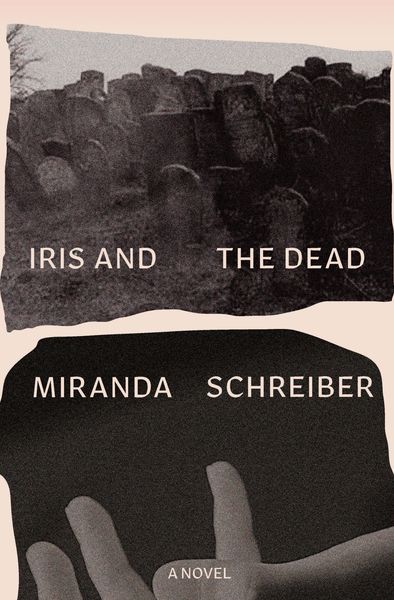

Read an Excerpt from Iris and the Dead, the Debut Novel from Miranda Schreiber

We're excited to feature the debut novel from acclaimed writer and researcher Miranda Schreiber today on Open Book. It's a haunting work that weaves elements of magical realism and folklore with grounded, true-to-life experiences of love, trauma, disability, and recovery. Both extraordinarily intimate and inventive, this is a voice that readers will want engage with and remember.

In Iris and the Dead (Book*hug Press), the narrator of the story explores a relationship with the titular character, a counsellor with whom she formed a strange and almost violent bond. The effects of this are powerful and devastating at times, but after recovering from the fallout, the narrator is ready to speak to Iris and tell her how she has changed the course of her life. She reveals what was going on below the surface when she knew Iris, and what she has learned since they spent their complicated and traumatic time together.

The novel is a spellbinding look at the shifting of memory and morality, the power dynamics of abuse, and the sexual dynamics that are at play in some of these relationships. Direct and heartfelt, this diaristic view into the narrator's life will be marvelled at by readers.

Without further ado, here's an excerpt from this stunning debut for all of our readers!

An Excerpt from Iris and the Dead by Miranda Schreiber

In the underworld, in a hearth, my great-grandmother Regina—who entered the world of the dead at fifty-three—sits in the middle of a circle of her children and burns meat for the goddess of silence, Mater Larum. The rite, as Ovid describes it, is intended to bring silence, muteness, for the benefit of the family. The offerings must move toward earth. In the underworld, this means they must rise upward.

The ritual is performed perfectly. Mater Larum is moved by the fragrance. She looks down and takes my mind. She brings it to the world of the shades and gives it to Regina. Grateful for the opportunity, Regina uses it to watch the sun burn over Budapest. Maybe afterwards she has dinner by the water. No one would reprimand her for this, for who would deny the dead a day of light?

Perhaps she passed the mind around. Maybe her children had the chance to use it to take things they wanted from the land of the living.

An exhale in a miserable part of the world. Grace for a moment. There is no logic in which this isn’t just. The lucky deny the wretched exist, but they do. Forms of death abound, even in the land of the living. The gods love someone; then they love someone else.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

The world of the dead is as different from waking life as dreaming is: an alien place. As the dead family immerse themselves into the land of the living, I recede into death’s dimensions. Each skill lost to me is a skill gained by the dead. I forget; they remember. I trip; they regain the capacity for motion. I am gradually exiled; they return. I no longer need sweaters in October; goosebumps rise on their arms.

When minds vanish, they cannot go all at once. Instead, they change possession gradually. The dead family receive my mind from the goddess of silence in handfuls like it is yellow grass. They acquire it slowly, evading detection. What could be said to the dead to contest what they’ve done? If there is one mind and six people who need it, why should it not be divided among us?

Their First Years in the Land of the Living

When the morning sky yawns, the mind, now a possession of the dead family, is put to use; it allows my great-grandmother Regina and her four children to leave the underworld, giving them their just ration of experience in the land of the living. At first they can only do simple things. Together, they all watch the clouds. Regina’s daughter Rose takes a walk. It is not so easy to wield the mind; it switches possession slowly and, anyway, there is no natural integration of a mind that is not one’s own. But they adapt. They do more as they gather more of it, welcoming the alterations in consciousness and life force. Regina’s son Leo exacts a powerful and awful revenge on an enemy.

The family of five seeks out different places, sees constellations wheel around the earth. Chances rain down. It is beyond their power to give back the mind. The loss of a mind, by their standard, is a puny evil. They desire time and now they have eternity, or at least as long as my mind sustains them. Like shadows they walk into houses that used to be stores, into the concert hall that was a shul, into a stolen printing press. They search for people who survived the war who look a little like them, who, protected by heaven, are still living in Uzhhorod. These people seem childish even in old age. Their beliefs, formed by their memories of luck and survival, lack the conviction that death can happen even to them.

The dead family write a series of notes full of anger. Their writing lacks coherence and suffers from tunnel vision because, at this point, they have not learned to use my mind properly.

It is only a twelve-year-old mind that they have taken, underdeveloped and constituted by adolescent rage. The primary desire of such a young mind is justice. And the primary desires of the dead are activity and expression.

______________________________________

Miranda Schreiber is a Toronto-based writer and researcher. Her work has appeared in places like the Toronto Star, the Walrus, the Globe and Mail, BBC, and the National Post. She has been nominated for a digital publishing award by the National Media Foundation and was the recipient of the Solidarity and Pride Champion Award from the Ontario Federation of Labour. Iris and the Dead is her debut book.