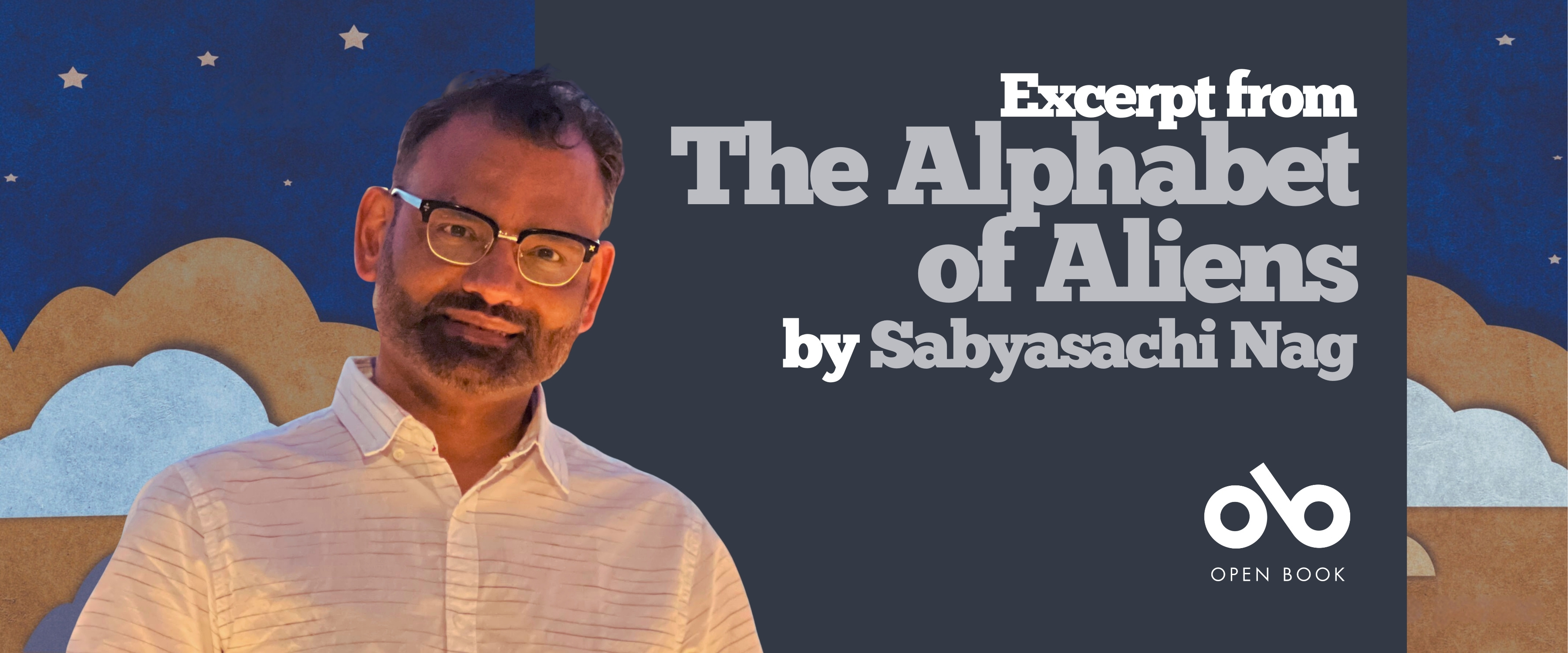

Read an Excerpt from THE ALPHABET OF ALIENS, the Exciting New Poetry Collection from Sabyasachi Nag

The exciting new collection of prose poems from Sabyasachi Nag moves through the unsettled spaces of migration, belonging, and in-between states. Drawing on lived experience as well as imagination, the work blends autobiography with dream logic, shaping a book that feels part diary, part travel record, part field notes from unfamiliar terrain.

Playful and precise, the poems in The Alphabet of Aliens (Mawenzi House) make room for the strange and the tender. Everyday objects shift into something else entirely, carrying the weight of displacement and transformation. With humour and quiet wonder, the collection traces what it means to pass through places, to arrive without fully arriving, and to live with the persistent pull of elsewhere that shapes many migrant lives.

We've got a couple of poems from the collection to share with our lucky readers today, so carry on and check out some lyrical goodness!

Excerpted Poems from The Alphabet of Aliens by Sabyasachi Nag

The Alphabet of Aliens

A for apple, B for blow-in. Aliens love them. Everyone knows it. But

when the boy comes home he chews on his blood. When the girl

comes home she chews on her case. And deaths come dressed like

deferred action, deportation. E for education; F for family, G for

government action, inaction, requital, retribution. The homeless

move like a shadow infantry minus horses. And when they come

invading, they act like ants. Because ants crave sugar. Ants make

sugar. Ants can’t do without an alphabet that has no apple sugar. The

boy says he’s the ant with a joy jug in his head, the owl with a sugar

heart, the parrot with a sugar tongue made from cochineal bugs. The

boy builds tunnels. The boy loves fables. The girl pulls her red tongue

to the mirror. She makes chances with the make-do name; makes

dates in make-do calendars. In a country of chained migration, her

alphabet has no letters; wax walls made of here, elsewhere, soul,

freedom. He loves being waivered. She hates being X-rayed. It’s hard

to skin him, harder still to parse her yak-belly alpha beta theta. Not

the usual twenty-six. Not the zigzagged zebra of merit and quota.

I know my hunger. Speaks in multiple tongues—appeal, affidavit,

asylum, amnesty, adjustment of status. Aliens are for apples. Apples

at the start, in the middle, and at the end. Apples for all seasons,

apples in every grocery aisle, apples in every drug store. Sweetness

spiked in sin. Apples, for centuries, since Eden.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

The Alien Fear

Having escaped their fate in the parliament of punks the alien is

scared of the heart’s inevitable collapse. When they enter a field

of corn, cut in halves by the alien green, angled toward the horse

hooves in the alien sky, they fear they will supplant ancient chants of

elsewhere with anthems of crickets here, shadowing the gold tassels

dancing the wind. When they tutor the child with deep philosophies

of the aspen and pine, they fear they’ll lose the songs of origin that

healed their wounds. And in the heat of their humiliations, they cook

their poppies. When they dig the cold ground to bury the dead, they

fear they’ll forget their debts. Before they offer their final word for

the bull-headed children, all set to scatter around alien oceans, they

ask for time, because they don’t want to be lonely again, because

their loneliness has no limits, because their ruin is the only one they

remember, because their dreams look like calluses on empty hands,

because the creases crossing eyes have cracked the mirror, because

their history burned a hole into the heart and the blue morning is

like turned milk and hurt is the only resting place until afternoon.

The alien fears new bridges in the offing after old walls have fallen.

In the pothole of rotten rain, the alien is anxious they’ll be asked to

puncture their own belly and aspire the blood, because they need

work, and they remember ancestors who were asked to build walls

with bricks from broken bridges.

___________________________________

Sabyasachi (Sachi) Nag is the author of Hands Like Trees (fiction; Ronsdale Press, 2023) and three previous collections of poetry, including Uncharted (Mansfield Press, 2021). His work has been published in numerous journals worldwide. He holds an MFA in fiction from the University of British Columbia and is an alumnus of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, Simon Fraser University, and Humber School for Writers. He is the managing editor at Artisanal Writer, an online journal that explores books, lit craft, and theory. When he’s not reading or teaching Creative Writing, he enjoys going paddling with his wife and son in the Great Lakes near Toronto.