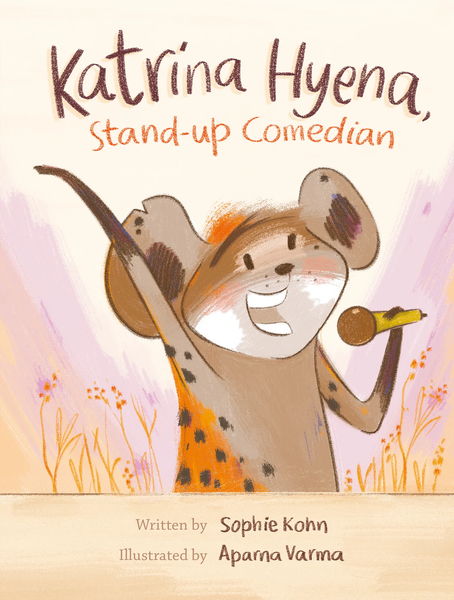

Sophie Kohn Celebrates the Power of Laughter in Katrina Hyena, Stand-up Comedian

A multi-talented artist who teaches humour-writing as a specialty, Sophie Kohn is no stranger to the effect of laughter and the empowering nature of humour as it develops in young people. This is a sentiment that is squarely at play in the new early chapter book by the author.

In Katrina Hyena, Stand-up Comedian (OwlKids Books), the titular character is always laughing because the world is super funny to her, and not in the way that her clan does, to warn each other about impending danger. This frustrates Katrina's kin, and has them constantly rushing to protect her when they hear her laughing.

At an impasse and unable to control this quirk, Katrina stages a stand-up show for the clan, and tries to help them relax instead of constantly being hyper-aware and afraid of the threat of one Gary the Lion. This hilarious chapter book will have young readers developing their own jokes and sense of humour, and celebrates self-acceptance and the differences that make them who they are.

We're thrilled to chuckle along with the very talented Sophie Kohn today, as she shares her insights into this new book in this Kid's Club BFYP interview!

Open Book:

Tell us about your new book and how it came to be.

Sophie Kohn:

In 2020, I was on mat leave with my son in the middle of a global lockdown during the terrifying early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. I was feeling these seemingly endless concentric circles of isolation – the isolation of new motherhood; the isolation that came with none of my friends or family being allowed to come over and help me get oriented postpartum; and the isolation of having taken a year away from my job as a head writer on CBC Radio and all the creative momentum I’d lost by hitting “pause” on my career. I was reading to my son constantly and spending time with dozens of baby and kids’ books every day and I became really fascinated by why some kids’ books were incredible and others fell flat. What accounted for that difference? I got so interested in how the writing and the art worked together in a kind of dance (or failed to, in some cases), and that delicate balance between gently offering kids a useful message about life while not being too heavy-handed about it. That got me thinking about maybe trying to write a short kids’ book myself, which felt like the perfect mat leave project given that the only free time I had came in random 20-minute bursts while my son was napping. Attempting to write a novel or something under those circumstances would have felt too daunting. But a handful of pages, minimal writing, and a few snappy jokes? That felt doable, and it ended up becoming a much-needed way of reconnecting with the creative identity I’d really been missing since giving birth.

OB:

Is there a message you hope kids might take away from reading your book?

SK:

So much of childhood involves being forced to assimilate to everyone around you: in school everyone has to learn the same way, take the same kind of tests, get the same grades, behave a certain way, talk only a certain amount, and defer to authority figures on just about every aspect of the day. Same with team sports and other extra-curriculars, friend groups, families, religious institutions, and society’s rituals around holidays. There’s so very little room for a kid to just be weird and different from everyone around him. There’s so little messaging that this is okay, that this is welcome, that this is a good thing. This is so tragic because I think a lot of kids are walking around with brains that work a little differently, with eyes that see different colours from everyone else, and with ideas and jokes and opinions and dreams that are a little “out there” – and they gradually learn to suppress all that stuff and even be embarrassed by it. Katrina Hyena is talking to those kids. I hope the book helps them feel seen, supported, and celebrated in all their strangeness and uniqueness. I hope it makes them start to see their quirks as something to lean into, rather than something to desperately edit out of their personalities.

OB:

Is there a character in your book that you relate to? If so, in what ways are you similar to your character and in what ways are you different?

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

SK:

I relate a lot to Katrina, which is probably why I created her. As a kid and an adolescent I was always laughing at inappropriate times and escaping into humour when life got difficult. I’d also say that the primary way I’d make new friends or create connection with another person was through humour. But as Katrina could tell you, the world doesn’t always receive that stuff so well. Like, in high school, I definitely earned myself more than one detention for intentionally provoking my friends and making them burst out laughing during morning assembly. Much like Katrina, I found standup comedy to be an excellent outlet for these tendencies. Unlike Katrina, I’ve thankfully been surrounded by very similarly-minded friends most of my life who are just as ridiculous as I am, so I haven’t generally experienced too much of the loneliness she feels as a result of being so misunderstood. Also, I’ve never been actively pursued by an enraged, hot-sauce-wielding lion. That I know of. So I’m pleased about that.

OB:

What was the strangest or most memorable moment or experience during the writing process for you?

SK:

Writing a fictional stand-up comedy set that a hyena would perform to a group of other savannah animals and that would also make sense to an audience of 6-year-olds and make them laugh was one of the strangest writing challenges I’ve had in a while. I spent a lot of time staring into a blinking cursor during that part of the writing process. I was initially at such a loss; it was such a hilariously specific situation. But perhaps the most memorable part of that time was when I was trying to write a joke that Katrina might make at a dung beetle’s expense. And I truly could not think of one. By some miracle, my then-2-year-old son was in the middle of potty learning and also becoming very interested in the letters of the alphabet. So we’d recently taught him the alphabet song. One day he was sitting on his potty and he spontaneously burst out singing, “L, M, N, O, POO!” and started laughing maniacally at his own joke. He seriously laughed for like 10 minutes straight. And that was it. That was absolutely the answer to “how does a dung beetle sing the alphabet?” So now he’s got a published writing credit at the age of 2. I love this for him.

OB:

What do you need in order to write – in terms of space, food, rituals, writing instruments?

SK:

The most important thing I need is quiet. Some people can write in a café where the music and the snippets of conversation and the barista’s shrieking steam wand combine to create a soothing soundscape that propels them forward. I can’t do this at all. The sounds yank me out of the work, rather than inviting me to settle into it. The other important thing I need is beauty. My home office window looks out onto forest and a big expanse of sky, and I find being reminded of the vastness of the world and my very insignificant presence within it is good motivation to really do something creative with my time on earth and get some writing done. And then the last thing is some genre of warm drink, like matcha or hot chocolate. That helps a lot, for some reason I can’t explain.

OB:

Do you feel like there are any misconceptions about writing for young people? What do you wish people knew about what you do?

SK:

I feel like a lot of people assume that writing for kids is somehow easier than writing for adults. After all, kids’ books are much shorter, they have bright colours, a cute story, and a neat and tidy ending where everything gets resolved. I maybe even carried around a bit of this misconception myself when I was starting out. But oh man, it is not easier than writing for adults – it’s just hard in a totally different way. It’s a bit like assuming writing a tweet is easier than writing a paragraph. Perhaps in some ways, but think about how much that tweet has to accomplish in so few words, without the luxury of stretching out that you have when you write a whole paragraph. It’s just a totally different brain muscle. Delving into the uniquely weird psychology of 6-year-olds, figuring out what genuinely makes them laugh, understanding how to work rebelliousness into the story in a way that feels fun and thrilling to them but not stressful and scary – that is deep, complicated work. That requires you to revisit and reinhabit your inner child when you probably haven’t done that in a very long time. And then: telling the story and unfurling the plot in a way that creates suspense and convinces them that reading is fun. Gently weaving a hopeful message about life through your pages. Choosing an animal character that hasn’t already reached a total saturation point in the world of children’s entertainment….but not too obscure of an animal – one they’re familiar with. Whew. Writing a kids’ book was a level of mental Tetris I had never attempted before. And it was a lot.

OB:

What defines a great book for young readers, in your opinion? Tell us about one or two books you consider to be truly great kids books, whether you read them as a child or an adult.

SK:

“The Quangle Wangle’s Hat” by Edward Lear is a book my parents read to me as a kid, and now I’ve been reading it to my own kid (the exact same battered copy). It’s such a fantastic example of an author who’s having a total love affair with language. It’s SO much fun to read aloud because the language is part real, part nonsense, and there is so much musicality and rhythm sparkling in every sentence. Both the words and the story itself are super-weird and almost hallucinatory, and what really shines for me in this book is how much genuine fun the author is having just playing with words both real and invented. The art does a great job of supporting this vibe – it’s neon and bizarre and very visually detailed and busy. I read this book to my son for the first time before he was speaking much and he was DYING laughing, not at the story itself because obviously he was too young to understand it, but just at the funny sounds going on in the words, the unexpected rhymes, and the general linguistic gymnastics that were happening on every page. And I think it says a lot about the book that it could reach him on that level before he even had any vocabulary or comprehension of plot. I also love this book because Edward Lear is absolutely unapologetic in his weirdness. That’s really crucial in a kids’ book. He creates this absolutely bananas world and writes about it with such confidence. He goes all in. And that makes the reader go all in, too.

_____________________________________

Sophie Kohn’s work has appeared in the The New Yorker, McSweeney’s, and Reader’s Digest. She teaches humour writing from her home in Nelson, British Columbia.

Aparna Varma is an illustrator for books and stationery with a bright sense of color and humor. Born and brought up in India, she spent many of her formative years in Botswana, Africa. She also works as a creative producer in animation and currently dreams and draws in Toronto, Ontario.