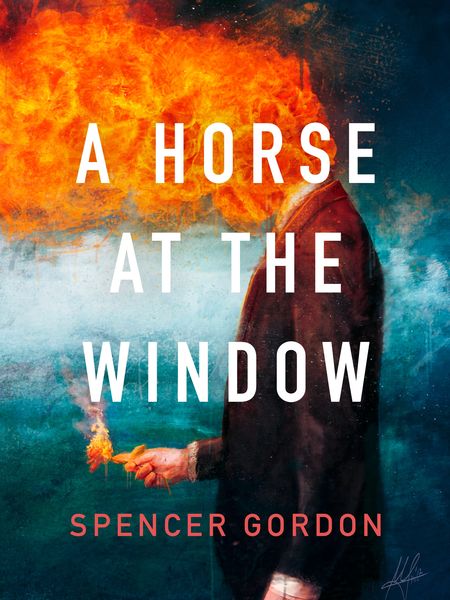

Spencer Gordon Bends Form to a Wondrous Breaking in A Horse at the Window

As an author who has been part of the CanLit scene for over a decade, Spencer Gordon has experienced and observed a world in flux through the sometimes hopeful, and sometimes necessarily disillusioned eyes of an artist that thinks deeply about the moment they're living in.

After a few years away from writing and publishing, Gordon has returned with a wonderfully strange and powerful collection of, well... It's a little bit difficult to say, but the closest description of the form would be "dramatic monologues." Whatever the publishing world might want to call these pieces, they are profound glimpses into the jawdropping, terrifying, sublime, and mundane.

A Horse at the Window (House of Anansi Press) blends elements of prose poem, faux memoir, online diatribe, and philosophical investigation, all to explore vignettes that illuminate the complexity of contemporary consciousness. Whether the reader visits with an aspiring writer who is trying to compile fragments of the 2000s to recreate their personal history, CEOs who enter nightmare realms where they lose their wealth, or the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, Gordon draws us all along with an assured if anxious hand, and shows us the beauty of Zen amidst all of the noise.

Immerse yourself further in this singular collection with this Going Pros and Cons interview with the author:

The thing that surprised me most about the publishing process:

Let me take you back to my sweet naivety. When I was young and foolish, I had the rational understanding that books wouldn’t materially or spiritually change my situation, my residency in the world. But I had some unvoiced, unrealized, irrational daydreams about how … I don’t know, things would be different after I became a published author. The world would re-arrange itself, somehow. The sun would shine sweeter. I’d be more artistically enmeshed, enjambed, with peers of fellow feeling. I would be living more authentically, or something.

In some shape or another, these were a few of the assumptions and dreams underlying my expectations: at the very least, that things would change, and for the better. And I tell you: I can feel this psychic energy beaming out of those who are still aspiring authors.

But—surprise surprise—when you publish, the world stays exactly the same. It’s you who changes. It’s your obligation to not change for the worse.

The advice I would give someone publishing a book for the first time:

I would advise you to invest your energy solely into making the book as good as possible, within all reasonable means of doing so. Enjoy the warm experience of being edited, of having an editor work hard with you on creating something beautiful. Years from now, all public appearances, accolades, awards and gigs—or, more accurately, the lack of them, the paucity of attention—will be forgotten. The last thing that will fall into the void or abyss of memory is the book itself. So: work diligently on making yourself proud of the text. Don’t become despondent or defeated by how your darling book will get invariably overlooked or ignored, or by the casual cruelties of those in and outside the business. Most small press titles go out of print and get mulched by their publishers—and no one cares if you ever publish again.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

The advice I would give someone trying to get a book published for the first time:

I would say, at the risk of sounding simplistic: stay strong, bud! There’s nothing you can do to influence an acquiring editor (or board or committee of editors…) other than basic stuff you’ve already heard about: submitting a clean manuscript, abiding by submission guidelines, and not following up too soon or too often, or too annoyingly. I would recommend submitting to many publishers at once, even if they forbid it expressly. Ignore their rules, because your manuscript can disappear or fall through the cracks very easily and all it takes is one lucky ‘strike’ to light your fuse.

I would also say: be patient. My heart goes out to all of you waiting. You might roll your eyes or say, “I already know that, I’m a big boy/girl,” but it’s good to hear it again, especially if you imagine me saying it to you with eyes full of compassion. The publishing pipeline or cycle (or whatever) is shockingly long. It might be nine months to a year before you hear back from a press (even if it’s an unequivocable ‘no’), or you may simply never hear back at all—it’s happened to me. And, joy of joys, if it’s a yes, you might still need to wait two or three years before the book is released!

All this to say: you must go into the entire submission and publication process with the patience of a saint, or monk, and work on other things in the meantime. Realize that it’s an indifferent world, with few rewards and many humiliations and indignities. You must be a particular kind of masochist to stick it out, and if that’s not really your kink, then don’t bother.

My favourite part of the publishing process:

A book starts as a sense perception. A fleeting thought or a feeling, lasting for a few nanoseconds. Then it gets wrapped up in all sorts of thinking—big, compounded, entangled delusions. Years later, and poof: there’s a physical object in your hands. It’s a pile of glue, ink and paper with your name on it.

The most profound, emotional part of “the publishing process” is that first moment when you see all that complicated thinking and feeling made manifest into form. It’s humbling and frightening. Was it worth it? It once seemed so important—recording and communicating your dream life, your private fires; seeing physical testament to the sweat and labour you poured into its container. Are you happier now that those dreams have another, marginally extended life of misinterpretation?

My least favourite part of the publishing process:

The knowledge that if I don’t promote my book, no one will read it. And if I do promote my book, a handful of people will read it, but then I’ll look kind of groveling and pathetic in doing so. This is a grim trade-off. It only feels worse with time and experience.

All this to say, please buy A Horse at the Window (House of Anansi, 2024).

What I think about MFA programs:

Since this interview seems geared toward aspiring or ‘emerging’ writers, I’ll talk to prospective students here.

Please know that you’ll never pay the MFA tuition back through poetry, say, or literary fiction. The degree is an expensive investment in your future candidacy for publication, publicity and esteem, not in your financial wellbeing. Publication, publicity and esteem have no financial associations. There are some exceptions here; for example, if you want to teach at the college level in Canada, the MFA can sometimes get your foot in the door, but I wouldn’t recommend doing this. In fact, if you want to teach, it’s much better to get an MA, which can lead to a PhD and better prospects.

What MFAs do is get your face and your work in front of better-connected and more established writers and editors. If you can impress them suitably, they’ll be instrumental in introducing you to the wider world of publishing (and mainly, the acquiring editors at relevant publishing houses). MFAs also create—artificially, of course—a coterie of peers. Luckily, you and your peers will share some genuine affinities (despite your inauthentic union) and may even have the energy to publish and support one another.

It’s possible to learn a few things about craft and dedication, too, but remember that most of the writers used as ‘mentors’ through MFA programs are not necessarily good teachers. So don’t expect to emerge knowing how to write (lol). When looking for a mentor, look at someone who’s got chops and a willingness to teach, to edit and mentor, rather than simply someone you think is an amazing artist.

Ultimately, you can write and publish just fine without an MFA, though it might take you a fair bit longer to break into the world and find your connections and ‘people.’ So, how much is this worth to you on a financial level?

What I think about literary awards:

Getting nominated and then given an award? It’s got to be an amazing feeling. Praise and gain are fundamental reasons we torture ourselves with work, art, love. It must be nice to get recognized and rewarded for your work. Like winning a race, getting a pat on the head, acing an exam, and winning the lottery, all at once. I imagine it opens doors to new, fun experiences that would otherwise stay shut.

On the flip side, we need to be very careful about how we talk about awards to avoid deluding ourselves. Awards have no relationship with aesthetic quality or merit—as if these things could ever be measured scientifically. That means no one, no work, ‘deserves’ an award over someone or something else (saying an award is “well deserved” is utter nonsense). Juries give awards according to subjective feelings, moods, grudges, crushes, the urge to make consensus, fear of having to defend questionable choices, and to serve political, ideological campaigns.

I think elevating, celebrating art is one thing. But the power and politics of award dinners, galas, ceremonies—filled with pageantry and pomp—is typically disgusting. I like my art a little bit punk, and would rather write books for free, forever, with zero chance of an award, than put on a performative tux and lick the boots of the C-Suite in some humiliating ritual funded by a bank. But that’s just me. I can understand the need for validation. I love money so much that I’d even work a full-time job for it, so I’m not immune!

What I think about writing grants:

Grants are great! Why not? I mentioned this a few years ago on Twitter, but I think grants would be much better if we assigned them by lottery. Think about it: it means a better distribution of funds across the entire writerly spectrum—i.e., the same people don’t get potentially hundreds of thousands over the course of their lives while others get squat. It means juries don’t need to do that sad handwringing thing about making ‘tough decisions, so many quality applications, can only choose a handful,’ boo hoo. Winners won’t gloat on social media, like they do currently, and losers have fewer reasons to despair or gnash their teeth; that’s greater equanimity for all (and with the lottery system, there are still ‘losers,’ so the powers-that-be can preserve a sense of hierarchy). As with my thoughts about awards, grants-as-lottery also further dismantle the impossible, illogical notion that art is ‘objectively’ good or bad, or worthy or not worthy of tax-payer support, based on the passing whims of other moody artists.

Finally, and equally as important, this process is funny, or way funnier than our current self-serious systems, which is partly the reason why members of our arts councils, the Adeptus Administratum, will never consider it. Maintaining the illusion of serious business, the ranking of merit, the hierarchy of cultural production, etc., are essential to their very being.

____________________________________

Spencer Gordon is the author of the poetry collection Cruise Missile Liberals (Nightwood Editions, 2017) and the short story collection Cosmo (Coach House Books, 2012). He co-founded and edited the literary journal The Puritan for a decade and has taught writing at Humber College, OCAD University, George Brown College and the University of Toronto. He works as a principal associate for Blueprint, a non-profit research organization dedicated to solving public policy challenges. Follow him on Twitter/X at @spencergordon and visit his rudimentary website at spencer-gordon.com