The Griffin Prize Poets on Writers' Work Days & Favourite Canadian Poems

The Griffin Prize is not only one of the biggest literary prizes in Canada; it has become one of the most prestigious and influential poetry prizes in the world, annually honouring one International and one Canadian winner.

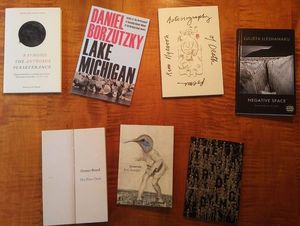

This year, two writers and two writer-translator teams are nominated for the International prize: Raymond Antrobus for The Perseverance (Penned in the Margins); Daniel Borzutzky for Lake Michigan (University of Pittsburgh Press); Don Mee Choi (translator) and Kim Hyesoon (writer) for Autobiography of Death (New Directions); and Ani Gjika (translator) and Luljeta Lleshanaku (writer) for Negative Space (Bloodaxe Books).

Three writers are nominated for the Canadian prize: Dionne Brand for The Blue Clerk (McClelland & Stewart); Eve Joseph for Quarrels (Anvil Press); and Sarah Tolmie for The Art of Dying (McGill-Queen’s University Press).

The authors of the seven shortlisted books will read in Toronto at Koerner Hall at The Royal Conservatory in the TELUS Centre for Performance and Learning on Wednesday, June 5 at 7.30 p.m. (you can buy tickets here) and the winners will be announced the following day, June 6, at an event in Toronto. The winner from each list will receive $65,000, with the finalists each receiving $10,000.

We're thrilled to be speaking to the finalists today about their work and the experience of being nominated. In our conversation below, Don Mee Choi tells us about the significance of there being 49 poems in Autobiography of Death, the poets each share their favourite Canadian poetry collections, and we hear about a grandmother's wool-spinning practice that doubles as writing advice.

Open Book:

Tell us about your nominated collection and how the project originated for you.

Raymond Antrobus:

I had been writing poems for years, without thinking of a collection. The Perseverance formed when Tom Chivers at Penned In The Margins reached out because he'd seen some of the poems I had published online and wanted to know if I had a book. I sent him about 15 poems and he liked them and said he wanted to start building the book with me. Honestly, it wouldn't have happened otherwise. I begin to see how the poems I was writing were speaking to / from and with each other, but honestly the process was pretty organic and couldn't have been planned.

Daniel Borzutzky:

The book is called Lake Michigan. In many ways, it’s a continuation of ideas from my previous projects which think about shared states of neoliberal violence between the United States and Latin America. This book in particular focuses on my hometown of Chicago, and imagines a prison site on the shores of Lake Michigan, which assimilates prison sites from Chile (where my family is from) and Chicago (where I live). It’s thinking specifically about police violence and the ways in which police violence is used to reinforce ugly privatization and economic practices, public policies that inordinately effect poor communities, communities of color, immigrants, and the city as a whole.

Dionne Brand:

The arguments in The Blue Clerk, arguments between the poet/author and the clerk, take place along several trajectories or rather along any trajectory. Some are arguments about humanism, some about the literary canon, others about painting, about art as political, about books, about creativity, about consciousness... etc...

Don Mee Choi:

I decided to translate Kim Hyesoon’s Autobiography of Death because it was her first collection in which all the poems were thematically and structurally interlinked. So the forty-nine poems in Autobiography of Death can be read as a single poem. And each poem represents one of the forty-nine days during which the soul wanders after death, before it moves onto its afterlife. I also felt compelled to translate the collection because when Kim sent the poems to me, she said that she had no choice but to write them because of all the unjust deaths that have occurred in South Korea. She was referring to the recent tragic event in which 250 high school students drowned when a private passenger ferry heading to Jeju Island had capsized. Kim was also referring to the many deaths caused by the recent dictatorships, including the brutal military suppression of the pro-democratic May 1980 Uprising in the city of Gwangju. Whenever I feel compelled by Kim Hyesoon’s poems, I feel I have no choice but to translate them.

Ani Gjika:

Negative Space is a collection of Albanian poet Luljeta Lleshanaku’s latest two books, Almost Yesterday (2012) and Homo Antarcticus (2015). In it, although the people and places described could belong to any place in the world, we learn what it’s like for an entire generation to survive oppression. This is juxtaposed with the long poem that retells the story of Frank Wild, an explorer capable of surviving five expeditions to Antarctica, and yet unable to quite fit in civilized society. I was first drawn to Lleshanaku’s work when I read and translated her poem "Flashback III" in 2010, where she writes: "I have emerged cunningly from my genetic prophecy,/holding on tight to the belly of the ram/out of the Cyclops’ cave." These were the lines that seized my imagination — the Odysseus-like character, a powerful metaphor of the experience of many Albanians continuously trying to escape someone, something, trying to survive. I knew when I read that poem that I wanted to translate her work. I started with poems from Almost Yesterday. Then, as Lleshanaku was writing Homo Antarcticus, she would send me poems which I continued to translate until we had two books in one. We gave no deadlines to each other, but we were mutually passionate about the work and she gave me a lot of freedom with my decisions as a translator/poet.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

Eve Joseph:

Quarrels is a collection of prose poems broken into three sections – the first, a grouping of the more surreal poems; the second, an homage to the photographs of the late Diane Arbus; and the third, an elegy to my father. Having grown up in a home where truth and fiction were interchangeable, prose poetry, when I found it, seemed to speak directly to my own experience of how the surreal exists just below the surface of ordinary life. The form forced me to "play" with language in ways I had not done before. In the introduction to the anthology Models of the Universe David Young writes, "If you mean to write a poem and choose to do that in prose, you wrestle with an angel who knows more holds than you have ever dreamed of." Once I started writing the poems I was locked into a struggle with form, with myself, with a desire to reach for something I could not quite grasp. I did not have a project in mind when I began writing; rather, I was trying to wrestle with a form.

Sarah Tolmie:

I wanted to write a book about a topic -- a single, big topic, not a collection of disparate poems. One that I could pursue for a while, and see many sides of. That is how the book is constructed, as a series of steps or moves, each one a reaction to the former one (this reaction is often oppositional). So the order in which they appear is by and large the order in which they were composed; you can see that sound patterns carry over from one poem to the next, or through several, all over the place. In many respects it is one long poem in many parts. The death idea crept up gradually, chiefly because I already knew about the medieval genre of ars moriendi (as a medievalist by trade). As a topic it allowed me to do the two contradictory things I wanted: to puncture cheesy euphemisms, which I despise, with humour or irony, while still being able to write a few serious and meditative poems. The book is a balancing act between those two impulses.

Open Book:

Are there images, themes, or questions you notice recurring in your work? If so, what are they?

R. Antrobus:

Yes, I think language, family, history, education, and how these things help us find connections are themes in all my work so far. I deal with poem by poem, without thinking about the larger ideas until much later.

D. Borzutzky:

How we live with state violence. How we live with economic violence. How we live rhetorics of hate. How we survive.

D. Brand:

The violence of the world, the colours blue and violet, the tyranny of verbs, the history of water, the porousness of time.

D. Mee Choi:

I have noticed that wings appear repeatedly in several poems in Autobiography of Death—they appear as butterfly wings, bat wings, and also as ribbons. And when I asked Kim Hyesoon about them, she replied that once she went out to the night sea where the ferry had sunk and listened to the wailing parents of the school children. She said, "Really, it felt as if the ink inside a bottle as big as the Pacific Ocean was oscillating. I wept, wondering how I would ever use up all that ink, writing about all the unjust deaths, with my tiny pen as skinny as a butterfly’s hind legs?" Then later, almost at the end of my translation of the collection, I came to think that within what Kim calls "the structure of death" everything must be winged, ribboned, tiny, or skinny to create a surface tension to repel the ink.

A. Gjika:

In my first book of poems, Bread on Running Waters (2013), I’ve written a lot about memory, childhood, being watched, departures from and arrivals to other languages and places. Currently, I’m writing a memoir which names periods of silence in my life and what it takes that eventually gives one voice. I write about my relationship to and love for language, but also about growing up erased by and at arm’s length from a language chock-full of political lies, secrets, and harrassments. Translating Albanian literature is an attempt for me to bridge the gap with a culture and language that still continue to erase the names of those who’ve given back to it the most. I write about intimacy, and transitions, from one continent to another, from one language to another, from an era of secrecy to one of self-discovery and personal liberation. I am currently asking what is a well-behaved woman, and what story does she want to tell.

E. Joseph:

That’s a good question. One that might be easier for someone else to answer. I don’t intentionally work with particular themes but I do believe that we all have a few core questions we tend to circle in our lives. I’m interested in the idea of "return". How do we come back from the lands of loss? What parts of us remain? What parts of us return? The idea of "here" and "there" intrigues me. As noted by the late poet, P.K. Page, the difference between the two is only one consonant. These are the kinds of things that engage me.

S. Tolmie:

I am obsessed with rituals of all kinds. I think I always have been. This particular book is about the numerous, often unstated, rituals surrounding our contemporary experience of death. Most of these are secular, but as deeply felt and as carefully regulated as formally religious ones: what we say about death and dying to our children, in schools, in hospitals, in headlines, on FaceBook. However, all my books have revolved, one way or another, around rituals. The first book I published, back in 2014, was a long meditative novel, The Stone Boatmen, about the way three societies just beginning to undergo a renaissance dealt with the past in contrasting but finally interrelated ways: one through elaborate court ritual, one through poetry, one through a form of nature worship or animism. I made up many kinds of ritual for that book and it was incredibly satisfying. It also reinvented me as a poet, I know perfectly well: one of its protagonists was a court poet, Rose, and I went through her life with her from birth to death and remembered what it was to be a poet, having written nothing but academic prose for more than a decade. Trio, my first poetry collection, was about the ritual positions of love poetry and of dance, and the ways in which improvisation is necessary to both. That was followed by two novellas with baroque settings published together as Two Travelers; in one, "The Dancer on the Stairs", a stranger who doesn’t speak the local language learns how to communicate via the "protocol dances" they use to regulate their hierarchical society; the other, The Burning Furrow, is a kind of Scarlet Pimpernel story in which a central ritual that bonds people to their land gives the story its title. Then came this book, The Art of Dying. And coming out this month is a new novel, The Little Animals, which is about the rituals of science. It’s about Antoni Van Leeuwenhoek, pioneer of the microscope in the 17th century, and it’s full of technical processes (microscopy, glassblowing, genre painting) that are also private devotions. These private rituals of inquiry in Golden Age Holland and elsewhere formed a confluence that was, broadly, natural philosophy, and over the next century these were pooled and strained into the most important ritual of modernity: the scientific method. So, yeah, I see rituals everywhere. I love them. I will be writing about them forever.

Open Book:

If you were to recommend just one Canadian poem (or poetry collection) to readers right now, what would it be and why?

R. Antrobus:

Canadian poets I love off the top of my head include Anne Carson, Mark Strand, Shane Koyczan, Leonard Cohen, Margret Atwood, and I been meaning to check the work of Afua Cooper. I'm really interested in meeting Canadian poets and learning more about Canadian poetry, particularly from indigenous and Spoken Word communities.

D. Borzutzky:

The poems of Larissa Lai. For their frantic, energetic, life-affirming rhythm and voice. For the ways in which they interrogate what it means to be a human animal amid global capitalism.

D. Brand:

Too many to favour. One would not be a remedy, or a salve, or an answer. Or even a question. But a line from Leanne Betasamosake Simpson’s poem False Consciousness will do, “write, but only as labour in bringing opaque to purpose”.

D. Mee Choi:

Hoa Nguyen’s poetry collection Violet Energy Ingots, which was shortlisted for the 2017 Canadian Griffin Prize. In 2016, I heard Hoa read from her collection in Seattle, and it was the first time I have heard her read. Then she appeared in my dream the next morning—she had a severed tongue. Dreams have a way of condensing intense emotions, including experiences of our place or placeness in the world. The dream condensed for me my experience of hearing in Hoa’s poetry her emotional, historical, and linguistic displacement. Her language, poetry arises from such tongue—tongue of distance, loss, memory, and once severed home.

A. Gjika:

I loved Sara Peters’ collection 1996 (Anansi, 2013). I love it for the masterful control she has over voice, syntax, tone, and her lucid and seering imagery. She tells a story in a way that a reader can never forget it and I tend to remember her lines much like I do Emily Dicksinon’s because of the very real and intense power of her imagination. I can’t wait to read the new book she has just published, I Become a Delight to My Enemies.

E. Joseph:

I would recommend John Thompson’s Stilt Jack. I fell in love with this collection of ghazals when I first began writing. More than any other book, this one taught me about associative thinking and leaping poetry. Reading it was like seeing my own thoughts for the first time.

S. Tolmie:

My favourite Canadian poem is Ondaatje’s "Cinnamon Peeler’s Wife" and my favourite book is Carolyn Smart’s Hooked. Both create persona superbly. Poetry doesn’t always have to be first-person confessional. I often prefer poetry in created voices.

Open Book:

Tell us what a typical writing day (if such a thing exists for you) looks like while you're working on a collection.

R. Antrobus:

Honestly, there's no typical writing day. I snatch time and write. I spend most my time traveling and teaching and then I'm also reading a lot on the go. I did once rent a writing desk but I used it about three times in two months, I just couldn't write that way because it was too conscious. I almost have to trick myself to write, because I get a bit in my head about how marinated an idea has to be before it can exist on the page or in the air.

D. Borzutzky:

I don’t think I have a typical writing day. I squeeze writing in among the many other things I have to do. I write in bursts. I’ll write intensely for 2-3 week periods. I write late at night or in between this and that. I like to assimilate writing into the rest of my life. I haven’t had much of a choice in this regard...

D. Brand:

It is like any workday, I imagine. I put in the hours that the work requires. And then overtime because it isn’t done.

D. Mee Choi:

In Seattle, I juggle full-time work, home life, translation, and writing, so I only get to write on Saturdays, if I am lucky. But I am in Berlin right now for a year-long writing residency through the DAAD Artists-in Berlin Fellowship. So technically, every day is a writing day, which can be scary. I have been here only a month, and I am still settling down and dealing with much guilt about not working and also worrying whether I can really make every day a writing day. When I am not fretting too much, I read as soon as I am awake, then I do some research or write or translate for my new projects, then I go out for a walk in the late afternoon. Then I have dinner and turn into a pumpkin.

A. Gjika:

My writing days are not that typical in any way — I teach four classes every day and between that and translation, and life, I find time to write at irregular times of day or night. But there’s something all my writing days have in common. I work through what I may describe as a process of accumulation, or weaving, the way bees fly and collect pollen not just from one type of flower but a variety of — I am constantly thinking a poem or prose piece through the lens of everything I randomly encounter every day. In Albania, my grandmother, who was a storyteller and a translator of the Bible, and many women of her generation, spun wool, and the trick was to continue to spin it on her spindle so thin without it ever breaking. I am constantly working in this mode with my words and my story. Even when I’m not writing, I’m spinning, inwardly, the story I eventually will tell.

E. Joseph:

Most days are full of procrastination, avoidance, delay. When I find my way into writing (often after days of being alone and many, many false starts) a kind of momentum can sometimes build and time is altered. I can write for 10 hours on those days but they are rare. The poems in Quarrels were often hard work. If I waited for inspiration, I would get very little done. The paradox, the thing I often forget, is that showing up and doing the work sometimes is a doorway into the new and unexpected.

S. Tolmie:

I have no typical writing day, and I am always working on more than one thing at once – at least one poetry project and at least one prose project. I see my work as a speculative fiction writer and as a poet as fully continuous, though the pacing and scope of the writing experience is very different. I often use one as relief from the other. Writing poetry is more staccato, and writing imaginative prose has slower, longer arcs. However, I will write anything anywhere, on whatever device I am carrying, in ten-minute bursts between things (on buses, for example), on park benches, in waiting rooms. I write at home and at the office in longer stints, as long as I can get away with. I write a lot in bed. I write a lot, period. I do not plan, brainstorm, outline or look ahead. Nor do I count any of those activities as writing, pace what many writing handbooks say. Research is not writing either. Writing is putting one word after another in the form in which you expect other people to see it. Your brain does a tremendous amount of work in between times, but you don’t get credit for it as most of it is unconscious. The part you can pat yourself on the back for is the one-word-after-another part. That is a big enough task in itself; it just gets too complicated if you try to account for all the other things that you do in your life that make you into the person that you are (i.e., a writer). Or for your talent and your circumstances and your luck and all the contextual things. All parts of your life bear on your writing, but the work of writing is word-ordering. For me that happens everywhere, any time I can work it in.

____________________________________________

For more information about The Griffin Poetry Prize, please visit their website