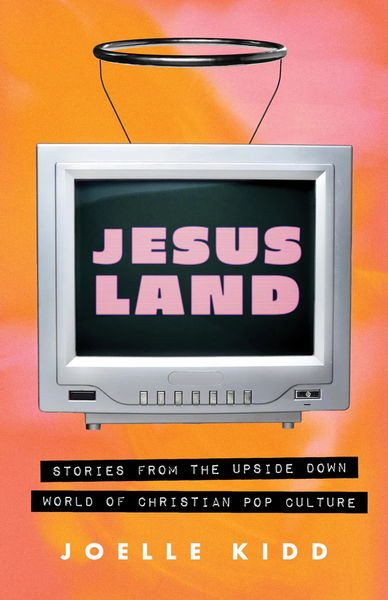

The Insightful and Empathetic Essays in JESUSLAND Explore the Draw and Danger of the Christian Pop Culture Movement

The new collection of non-fiction essays, Jesusland: Stories from the Upside Down World of Christian Pop Culture, is not your typical coming-of-age memoir. Set against the backdrop of early 2000s evangelical youth culture, this essay collection explores a world where pop music came with purity pledges, and fashion advice was filtered through scripture. Returning to Canada in her teens after several years in secular Europe, author Joelle Kidd found herself plunged into this world after being enrolled in Christian school. What she encountered was more than awkward youth group games or upbeat Christian radio, but rather a tightly woven subculture designed to shape beliefs, bodies, and political identities.

In nine candid and compelling essays, Kidd unpacks the messages embedded in the Christian media that targets youth. She examines how evangelical culture adopted the aesthetics of mainstream pop, including the branding, the celebrities, and the glossy magazines. All while promoting a set of values that discouraged questioning and demanded conformity. Beneath the cheerful surface, she finds a network of ideas that helped fuel a political movement with lasting influence on everything from reproductive rights to queer and trans visibility.

But Jesusland is also a book about memory and reflection. It captures what it feels like to look back at a former self, a young person who took abstinence quizzes in teen devotionals, and who wondered if her favourite bands were Christian enough. With no intention of being dismissive of all of this, the author asks what those moments truly meant. Kidd offers no easy answers, but she brings curiosity, care, and humour to the process of making sense of a past that still echoes in the present.

We’re delighted to welcome Joelle Kidd to Open Book to talk about writing Jesusland, navigating complicated legacies, and the surprising ways pop culture and faith continue to intersect.

Open Book:

Tell us about your new book and how it came to be. What made you passionate about the subject matter you're exploring?

Joelle Kidd:

My book is called Jesusland: Stories From the Upside Down World of Christian Pop Culture. My usual way to explain it is that it’s a book about the evangelical Christian pop culture of the early 2000s: the movies, music, magazines, comedy, and more that was being made for and marketed to conservative Christians in a decade that marked a high point for both religious fundamentalism and the commercial success of those industries, before the disruption of the internet.

But the other part of the book, and the reason I became so interested in this subject matter, is a memoir of my own life in that decade, during the formative years of my childhood and adolescence, when I attended an evangelical Christian private school.

While I’ve certainly spent a lot of time thinking about how growing up in that environment affected me, I had never really thought about writing about it until I began coming at it through the angle of pop culture. When I really started researching and exploring the pop culture I remembered from childhood (the Christian pop bands I’d sing along to in my bedroom, the books my teachers assigned us to read, the Christian teen magazines I’d read in my school library), I found a rich and complicated world of commerce, religious fundamentalism, and politics.

The book is made up of nine essays exploring different segments of this strange world, and while I hope there’s a lot of humour in it (especially for readers who can relate to this subculture), I’m also passionate about the subject matter because I think it offers some very relevant insight into our culture and politics today. Consider the blockbuster Left Behind book series, which shaped contemporary Christianity’s vision of the end of the world--co-written by a founding member of the Moral Majority. Or the early 2000s influx of Christian lobbying groups who claimed credit for the election of George W. Bush--and laid the groundwork for a politically powerful Christian nationalist base who would later elect Donald Trump.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

OB:

What was your research process like for this book? Did you encounter anything unexpected while you were researching?

JK:

This book required a lot of research! I basically spent the better part of a year holed up in the Toronto Reference Library (which, to be clear, I’m not complaining about).

My favourite part about the research for the book was the variety of sources I ended up incorporating, and how the subject matter necessitated an extremely broad and inclusive research practice. If you read through the source list, you’ll find academic research, statistical studies, and historical sources, but you’ll also find Reddit posts and 2000s era blogs, social media ephemera, Christian news magazines, podcasts … and of course the pop culture media itself, which I sometimes had to hunt down via the generosity of strangers putting things on Youtube or through the Wayback machine. (I found it very gratifying to be able to go to the source of half-remembered videos, songs, and films of my childhood, using the magic of the internet.)

Strangely, the most unexpected and gratifying part of the research process for me ended up being the recognition I found when I began researching this era of my own childhood. For a chapter on purity culture and abstinence teachings, I collected responses via interviews and surveys of other people my age who grew up in evangelical environments, about their experience with abstinence teachings and how it affected their sexuality and expression. I was blown away by the responses, seeing so many common threads and elements of my own experience reflected back to me.

All his research made me feel much less alone. One thing about growing up in such a heavily religious environment is that you feel a little separated from “regular” secular society, so that recognition was very validating. It can also be very valuable to return to the images and ideas you consumed as a child, when you were just forming your perceptions of yourself and the world around you.

OB:

What do you need in order to write – in terms of space, food, rituals, writing instruments?

JK:

I’m not a very ritualistic person, as much as I’d like to be. I find it really hard to build habits or stick to schedules or do the same thing every day. There are pros and cons to this. While it’s not great in that I have to put an alarm on my phone just to remember to brush my teeth every morning, coming to accept this aspect of myself has been a bit of a strength for my writing life. I’ve learned that I don’t need to get up at 5 am every morning and write for an hour to finish a book; I can have a flexible schedule, I can write more when I feel more inspired and I can take breaks when the well feels dry.

It’s also helpful in that I’m not very fussy about where I write - I can get into a flow at home or in a coffee shop or on my phone on the bus. I sometimes write to music, sometimes to silence, sometimes outside, sometimes at a desk, sometimes in bed. I find changes of scenery conducive to getting through difficult parts of the writing and editing process.

I wrote a lot of this book (and did a lot of the research for this book) in the Writers’ Suite at the Toronto Reference Library, and I found it very helpful to have a clean, quiet place where I could come, think really hard for a few hours, and then leave. Writing as both a passion and a job is a tricky thing; your brain never really turns off, there’s no “leaving work,” but also some of the best ideas happen away from your computer. But having a little time and space set aside to work felt very generative at the drafting stage of this project.

Finally, and this is the hyper-practical answer, but I also realized what I really need in order to write is … time to write! As someone who’s always written ‘on the side’ in the hours squeezed around a full-time job, the years I took to complete a creative writing MFA were completely mind-blowing. It made me realize that it’s not just about having ‘enough time’ to finish something; an abundance of time, enough that you feel free to ‘waste’ some of it, actually makes the writing better.

OB:

What do you do if you're feeling discouraged during the writing process? Do you have a method of coping with the difficult points in your projects?

For me, one of the most helpful things is understanding that feeling discouraged is a part of the writing process. Accepting that I’m never going to learn how to not be discouraged at some point in the life cycle of any writing project has helped me view those discouraged feelings as a temporary state--sometimes even a helpful one. I’ve never lived by the motto “Don’t be a quitter.” As a proud and often quitter, getting discouraged with my writing used to be when I put a project in a drawer and never looked at it again. Now I just see it as a sign; it means I’m at a sticking point, and I have a few options: step back for a while; try something new; or start again and see what happens.

One method I like when hitting a difficult point in a writing project is to step away from that work for a while. I’m the type to have a lot of projects on the go at once, so while writing this book I would take a break and work on a fiction project, exercising my creativity but in a very different form. If I was getting mired in a draft of an essay, I’d work on some research; usually reading the words of other smart people would spark some kind of inspiration to keep going or rework my draft. If the research was getting overwhelming, I’d start freewriting, to see if I could clarify in my own mind what the essay was really about.

Another difficult point I ran into several times in the course of writing this particular book was the emotional exhaustion of dealing with heavy subject matter. In my case I felt it was important to go slow and not push through those difficult feelings, but give them some space to breathe, even if it meant the research for certain chapters moved a lot more slowly than others or that I needed more emotional support than usual.

OB:

Do you remember the first moment you began to consider writing this book? Was there an inciting incident that kicked off the process for you?

JK:

Some of the ideas that form the central core of the book have been percolating in my mind for a long time. In fact, I remember writing some of the thoughts that would eventually become key to these essays in my journal as a teenager, when I was actually in the thick of the Christian culture I write about in the book.

What became the actual book first started to take shape during a creative nonfiction course in my MFA program, taught by the amazing Kyo Maclear. I wrote the first draft of what is now the first chapter of the book to workshop in that class.

What I originally wanted to explore was a feeling I’d had as a kid: a kind of double culture shock that happened when my family moved back to Canada from overseas and I started attending Christian school. I was trying to capture on paper how weird everything seemed to me at the time, and how out of place I felt. The process felt a lot like digging around aimlessly in the dirt, and when I started writing about Christian music was when I felt like I hit on a root system - I started pulling and pulling and it kept coming up, diverging in all these strange and wacky ways, this idea of Christian pop culture. I could feel how much there was there for me, about nostalgia and growing up and politics and history and art-making and meaning-making.

OB:

Did you write this book in the order it appears for readers? If not, how did it come together during the writing process?

JK:

The finished book falls pretty close to the original order, with a few of the chapters rearranged to help the overall flow of the book as a whole. (Massive thanks to my brilliant editor Jen Sookfong Lee for her suggestions on chapter ordering!)

I’d never written something so large based on a proposal before, but I found that the exercise of ‘pitching’ the whole book before writing it provided a very helpful roadmap for the actual work of writing. Because the essays in the book are organized by topic, it was pretty easy to break down the researching and writing process essay by essay.

Within each chapter, though, there was a lot of juggling and editing and moving things around. Marrying together research and anecdote and criticism and humour was a tricky process and I’m so glad that I had such a skilled editor who had such a strong understanding of what I wanted the ideal version of this book to be, in order to help push me closer and closer toward it. I was also lucky to have writing groups, classmates, and friends I could show or read portions of the book to, for encouragement and to let me know if my jokes were actually landing.

OB:

What are you working on now?

JK:

I have a finished draft of the novel I wrote as my MFA thesis waiting for me to return to it, so I hope to return to that project this year. I also have a bunch of new ideas, both fiction and non-fiction, clamouring for me to attend to them. All I need to do now is find the time to sit down and write!

_______________________________________

Joelle Kidd is a writer, award-winning journalist, and editor living in Toronto. Her short fiction and essays have appeared in outlets including The Walrus, LitHub, Catapult, PRISM International, Prairie Fire, and This Magazine. Joelle holds an MFA from the University of Guelph’s Creative Writing program. Jesusland is her first book.