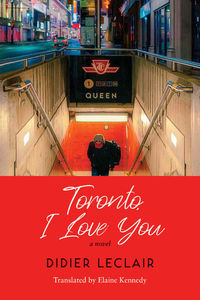

"There’s What You See and What You Don’t" Read an Excerpt from Didier Leclair's Trillium-Winning Novel, Toronto, I Love You

In Toronto, I Love You by Didier Leclair (Mawenzi House, translated by Elaine Kennedy) Raymond Dossougbé thinks, at first, that he's found a sanctuary in Toronto.

After fleeing corruption and violence in his home country of Benin, the freedom and equality in Toronto feels heady. But as he scratches the surface of the city, he finds that for all its excitement and opportunity, it is deeply flawed: wealth disparity, police brutality, and grinding poverty exist alongside green parks and shiny shops. And in the African ex-pat community, he sees the legacy suffering and racism have wrought in homes both old and new, with mental scars that hold back the men who call themselves Raymond's brothers.

An electric, absorbing portrait of a complex city, Toronto, I Love You is both a love letter to Raymond's adopted home and a call to arms. Leclair's vibrant, tight prose and breathless storytelling won him the Prix Trillium when the book was first released in French in 2000; now Mawenzi House and translator Elaine Kennedy have brought this powerful story to English language readers, and we're excited to share an excerpt here today.

In this passage, we meet Raymond as he descends into a boozecan — an illegal, after hours bar. Here we see his hopes and disappointments on display as he navigates the fraught social landscape of the ex-pat community.

Excerpt from Toronto, I Love You by Didier Leclair, translated by Elaine Kennedy

Toronto by Night

Koffi’s job was in the basement of a bland house on a lane with a pretentious name: York Gate Boulevard. Outside, there wasn’t a soul around. Everything was quiet. Koffi rang the bell three times slowly, then twice more quickly. The door opened, and a young girl with a rather sullen expression showed us in. She directed us to the basement, and Koffi invited us to follow him down. There was complete silence in the entrance, not a single note of music reaching my ears. As we descended the staircase, we started to hear a song, which was muted at first, then grew louder and louder. The steps led down to a smoke-filled room the size of a postage stamp. The place was furnished with a few rickety round tables, each surrounded by four or five chairs. Some people were gesticulating on a tiny dance floor, circled overhead by cheap multicoloured lights. Other guests, slumped in their chairs, were dozing in the din. An aging woman behind a mock bamboo bar was serving drinks almost mechanically, without a hint of a smile.

I was surprised by Koffi’s nightclub. What amazed me most was that none of this racket could be heard outside. Why did all these souls need to go underground, to sink into the bowels of the earth, when life awaited them above. There were some forty people in the basement— all black except one white man—bent on enjoying themselves to the point of passing out. They were writhing around like fish out of water, with the determination that only fish show before they die. The dancers, for their part, wanted nothing more than to drown themselves in the pleasures and delights of reeling bodies, covered in the salt of their own sweat.

The strong smell of smoke caught in my throat and made my head spin.

“Are you okay?” asked Koffi.

“Yes, just a little dizzy.”

Koffi took me by the arm, and we crossed the room to the bar.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

“Some good Jamaican rum’ll perk you up,” he said after ordering. “You weren’t expecting this, were you?” he added, pointing to the people on the dance floor.

“No... Not at all.”

“That’s how it is here, Brother! There’s what you see and what you don’t.”

Koffi slipped away to relieve the DJ, who was waiting for him in the booth. Bob and Joseph had dispersed and were chatting with people they seemed to know well.

The DJ that Koffi was replacing wasn’t a young man. He was the owner of the club and had decided to earn some extra money by turning his basement into an illegal nightclub. He’d posted his daughter at the front door. His wife was in charge of the bar and the cash, and his son had the task of throwing out the undesirables. He operated the control booth. Since he was getting on in years, he had Koffi take over for him some nights.

The mother, plump and phenomenally buxom, came over to us holding three beers. She handed me one and left immediately. Weaving her way admirably through the crowd, she skirted slender, thickset and transparently-clad figures before ending up back behind the bar. I watched her, my beer in my hand and my eyes already yellow from the rum I’d just gulped. Her gait reminded me of a bomb-disposal expert zigzagging through a minefield. And she was right to be cautious. This small place, smelling of smoke, sweat and beer, was above all a battlefield. Every overheated dancer was an explosive to be handled with care. The level of energy in the room could’ve set the entire house ablaze. What’s more, no one in this underground world had any regard for anyone else. We were in a realm that wasn’t part of ordinary life. No one had the right to lay down the law. The devil could’ve been any one of us, and he was not to be provoked.

The cheapness of the decor reminded me of certain places in Cotonou. The tacky ornaments hanging here and there created the offbeat atmosphere of clubs where people celebrate to forget that they don’t have money. The dull, distasteful lights were no longer flashing much. The air was growing thicker with smoke. I thought I was going to have another dizzy spell, but the beer took care of reviving me. The lights continued to dim, succumbing to jaundice, scarlet fever, and every other disease on the face of the earth.

A dance train came out of nowhere and snatched me up before I could do anything about it. Male dancers in an orgiastic mood were holding the hips of callipygian women. I was behind a man who was so drunk he was having trouble keeping step. I was holding up the rest of the train because he reeked so badly of rum that I didn’t want to get too close to him. Strong hands suddenly grabbed hold of my shoulders. Hot, nauseating breath said in my ear, “Hey, Koffi just told me about you, Brother! Follow me.”

I turned around and saw only a greying, black nape. The man sat down at a table with a beaming, gold-toothed woman. He pulled up a chair and insisted that I join him. His bloodshot eyes softened when I complied.

“Koffi told me that you’re from Benin. Is that true?”

“Yes.”

“Then you’re a brother! I’m from Upper Volta!”

“Upper Volta? You mean Burkina Faso.”

“Oh, yeah! I always forget that my country changed its name. You know, I’ve been here for such a long time.”

He roared with laughter at the mistake and relayed the incident to the obese woman, who showed all of the jewellery in her mouth.

“I’m Mathieu Zongo,” he said, shaking my hand with an iron grip. “And you are?”

“Raymond,” I replied, grimacing with pain, my hand being clenched.

“So, tell me! How are things in Africa?” he asked, his breath fouler than ever. His baritone voice was thick with whiskey. I pictured myself at the end of the evening with the same red eyes. He laid his hand on his girlfriend's thigh and whispered something in her ear. She laughed, gave me a sidelong glance, lifted all her weight, and disappeared into the crowd that was dancing more and more outside the dance floor.

“You like her?”

“She’s not my type.”

“Be careful, Brother,” he cautioned, chuckling. “Don’t be foolish enough to take a woman from here!”

“Why do you think I’d do that?”

“I don’t know,” he replied, gulping his drink. “I don’t have much faith in the young people I’ve seen landing here in the past few years. I wonder how you were all raised…”

Mathieu looked at me, a burning question in his eyes.

“What is it?” I asked.

“Well, you can’t even talk to me about Africa. That’s not normal!”

Mathieu emptied his glass, and his girlfriend returned with another drink. He thanked her with a slap on the hip.

“In my day,” he continued, “I would’ve jumped for joy to meet a big African brother just a few days after I arrived. You don’t seem to give a hoot!”

“Do you have a job for me?” I asked bluntly.

“No, I’m looking for one myself.”

“Do you have a place to share?”

“No,” repeated Mathieu. I could see the surprise in his eyes. That’s what I wanted. I didn’t like his brotherly tone.

“Koffi, on the other hand, gave me his bed. How do I know that you’re my brother? Because you’re African and you bought me a drink?”

The mixture of rum and beer was having a very bad effect on my mind. Mathieu’s fiery eyes widened. His amazement gave way to anger.

“Well, I’ll be damned! Africa’s really in a bad way. You listen to me, boy,” he said in a threatening tone. “I’m going to tell you a story that’s very short but important. There was once a man who was young like you. He fought for his country’s independence. When hatred and corruption were ravaging his homeland, he risked his life to denounce them. Then he had to go into exile to save his hide and keep his integrity in the eyes of his kids. Today, he’s sitting in a bar, far away from his family, with a young man who’s not showing him any respect. And he wonders if he would’ve have been better off becoming corrupt.”

We remained silent, looking at each other in that basement unknown to the outside world. His eyes rolled upward, shot through with blades of light, blazing with rage. When the blazing disappeared, I sensed that he was about to deflagrate inwardly, in a silent tumult on the verge of tears. That didn’t affect my insolence or my tone. I shouted that if young people like me didn’t respect him, it was because there weren’t any more young people in Africa, only desperate ones. It wasn’t a question of a prosperous future, but of survival.

I had offended a stranger who never would’ve spoken to me had he known what awaited him. He wasn’t the real cause of my anger. I’d spit venom for one reason. I wanted to part ways with the brotherhood of the oppressed, the very one in which I’d grown up. My anger was directed at a relentless enemy: imperialism. All Africans learned to stand in solidarity with the oppressed before they learned to read. With this man, it was the same old story. But I was in Toronto to turn the page. And no one, not even an unsung hero, was going to stop me. No one was going to shatter my dream.

Mathieu clenched his fists. I took this gesture as a final warning before he exploded. The little sobriety I had left enabled me to move away. I returned to the bar where another beer that Koffi had ordered was waiting for me.

Maybe Mathieu was telling the truth. Maybe he couldn’t be corrupted. It was too late for me to apologize. In any event, that Manichean world of oppressors and martyrs didn’t exist for me anymore, if it ever had. The scenario was too monotonous. I didn’t want to be part of any vicious circle anymore. I was determined to take people as they really are: human beings with their strengths and weaknesses. I couldn’t put up images of political heroes on my bedroom walls, like Koffi, anymore. I no longer considered anything sacred. Idolatry was often a reaction of the desperate. I’d decided to become hopeful again, and no Africanist brotherhood on earth could work for me. That’s why I knew that Mathieu, incorruptible or not, had no chance of interesting me. He hadn’t told me about himself. He’d told me what he thought of himself.

Much later on, Koffi played a series of slow songs. I looked for a partner in the darkness. It wasn’t easy to find one because most of the women were already on the dance floor, and the rest were in good company. Marvin Gaye was singing “Let’s Get It On” in his inimitable voice. His sound was purifying the air. Couples were clutching each other ardently and, in some cases, excessively. Joseph was leaning on a woman who was heavily made up and covered in cheap jewelry. He was clinging to her like a shipwrecked man to a life preserver in the open sea. Bob was dancing alone in a corner, an imaginary guitar in his hand. Koffi had left the booth and was whispering God knows what in the ear of the owner's daughter. Her mother was shooting dirty looks at them.

It was around seven in the morning when the club closed. The house emptied slowly, the guests trickling out. Somalians, Haitians, and Jamaicans emerged nonchalantly into the pale light. There was no colour in the sky. We were walking one behind the other as if we wanted to be in one last dance train. But our silence was too heavy. It betrayed our lack of enthusiasm. It wasn’t a silence of guilt; it was one of regret about leaving that underground place, that opaque world veiled in smoke, yet protective like the one before birth. The depths of the earth were also the womb of the damned. We left that telluric space reluctantly for the harsher, crueller outside world. Passersby on their way to work looked at us as if we were ghosts surprised by the light of day. We’d left somewhere as stifling as hell, but as exhilarating as a secret escape. I thought that life in Toronto should be as euphoric, but here celebration was confined to a suburban basement.

Some time later, I realized that Joseph had slipped out on us. He’d made off to his last dance partner’s place. The aroma of coffee wafting out of the shops was beginning to make my mouth water.

________________________________________________________

Excerpt from Toronto, I Love You by Didier Leclair, translated by Elaine Kennedy. Published by Mawenzi House Publishers. Copyright 2022 by Didier Leclair. Reprinted with permission.

Didier Leclair is a three-time finalist for the Prix Trillium and the recipient of both the Trillium and the Christine Dumitriu van Saanen book prizes. His second novel, Ce pays qui est le mien, was shortlisted for the 2004 Governor General’s Award for French-language fiction. Its English translation, This Country of Mine (2018) and was a finalist for the Toronto Book Awards. Didier Leclair was born in Montreal to Rwandan parents. He grew up in different African countries–Gabon, Benin, Togo, The Republic of Congo–and returned to Canada in the late 1980s. Since that time, he has been living and writing in Toronto.