"This Incredible Period of Chaos and Change" Alexandra Mae Jones on Why She Loves Writing Young Adult Literature

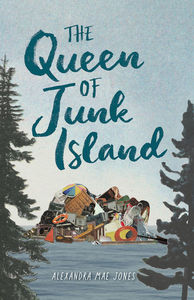

In Alexandra Mae Jones' debut young adult novel, The Queen of Junk Island (Annick Press), 16-year old Dell is dealing with adult-sized challenges, both internal and external.

In shock from the trauma of having her nude photos shared online without her consent, Dell finds herself shuffled away to her mother's remote cabin for the summer as if she's done something wrong. She finds a distraction in the form of her mother's boyfriend's obnoxious daughter, Ivy, who has been invited along. Ivy gets under Dell's skin in a way she doesn't totally understand, and as Dell begins to uncover family secrets in and around the cabin, she slowly realizes she is also uncovering secrets of her own, about desire and her true self.

The 2000s-set book captures its setting flawlessly while still feeling timely in its raw, smart portrayal of queer discovery, teenage social politics, and the legacy of family secrets. Jones' writing feels like a fierce love letter to queer girls and their depths and experiences.

We're speaking with Alexandra today about The Queen of Junk Island as part of our Bright Young Things interview series for young adult writers. She tells us about how young adult books speak to readers at a crucial time when they're deciding and discovering "how they want to move through the world", why she sees queer YA stories as more important now than ever, and how writing YA comes with a "higher degree of responsibility towards [the] reader".

Open Book:

Tell us about your new book and how it came to be.

Alexandra Mae Jones:

The Queen of Junk Island is the book that I have been wanting to write since I was a closeted bisexual teenager, even if I didn’t know it back then.

It’s set in the mid-2000s, and follows Dell, a 16-year-old girl who has been left reeling after her boyfriend posts nude photos of her online, causing huge strain between her and her mother, Anne. Spending the summer cleaning up the old family home after a previous tenant left garbage piled all over the property (including in the lake behind the house) seems like it’ll be a good distraction for Dell at first — until she finds out that Anne has invited Ivy to stay with them, the infuriating teenage daughter of Anne’s new boyfriend.

Add in a lot of confusing romantic tension and a quest to uncover secrets about a dead aunt who may or not be haunting Dell, and you’ve got QOJI!

This book was actually born at the University of Toronto way back in 2015 in a novel writing course which had very strict rules for what students could write: no genre fiction, literary realism only, past tense only. It languished as a sad first draft until I took an MFA in Creative Writing at the University of Guelph, and there I was able to actually think critically about why I was making certain artistic choices for the narrative, instead of writing to fit in a box. (Part of this resurrection of the story was being able to include the ghost storyline that I’d had to cut from the original idea!)

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

OB:

What, in your opinion, is unique about writing for young adults? What are some of the pleasures and challenges?

AMJ:

Writing YA means speaking to a time in a person’s life when they are starting to understand not just who they want to be, but how they want to move through the world. It’s this incredible period of chaos and change, where young adults are forming their values and their identity and everything feels hugely urgent and important to them. There’s so much material there, and the idea that my words could maybe play a small part in someone coming to understand themselves is amazing.

Also, considering the rise in homophobic and transphobic rhetoric that we’re seeing actively in the U.S. and the U.K. right now (and Canada as well, even if we think we’re immune), I think queer YA stories feel more vital than ever.

One of the big challenges of YA, I think, is finding the balance of art vs. teaching. There’s this idea that including didactic elements in writing somehow chips away at the authenticity or artistry, or cheapens the story somehow, but when you’re writing for children, the author has a higher degree of responsibility towards that reader, particularly if you’re writing about really heavy or challenging topics. So the question is, how do I write this story in a way that challenges the reader and makes them think, without abandoning a teenage reader in concepts that they may not have the life experience and perspective to consider fully? At the same time, talking down to a teen reader is the quickest way to lose their interest.

I think that balance of providing hope and guidance without sacrificing the nuance of the story is something I’ll always be trying to work out!

OB:

Is there a character in your book that you relate to? If so, in what ways are you similar to your character and in what ways are you different?

AMJ:

Dell, my chaotic mess of a protagonist, is definitely the character I gave the most of myself to. While she’s a different person with a different story, one of the big things I wanted to depict with her was this unique type of internalized biphobia and misogyny that I remember wrestling with as a teenager growing up in the mid-2000s. The lack of comprehensive sex ed and the fact that no one really talked about women and girls having desires meant that I grew up assuming that having sexual feelings or masturbating meant I was some sort of creepy monster. And since bisexuality was just a joke back then, when I started getting an inkling that I might like more than just boys, it just seemed like more proof of perversion.

Dell goes through a lot of the cruel and misguided thought processes I had at that time while she’s trying to sort through her relationship with her body, trauma, and sexuality. It’s one of the most difficult parts of the book, but one of the aspects that is the most important to me. Queer teens do make mistakes and I want readers to know happiness and self-acceptance can still be found after that struggle.

OB:

What was the strangest or most memorable moment or experience during the writing process for you?

AMJ:

Probably rewriting the whole manuscript from third to first person!

The first few drafts were in third person, and when I was trying to find my way back into the text during my MFA, I could sense that something was wrong in the overall framing of the story, but I was scared to rewrite it.

What gave me the push I needed was when Dionne Brand told me in an MFA fiction seminar that a short story I wrote in first person had a much stronger voice than the last piece I had brought to class — which, tragically, had been a chapter of my novel. So I rewrote the first chapter into first person and brought it to class, where it was pretty unanimous that first person was what the book needed. I’m so glad I changed it, as it really brought it back to life for me!

OB:

What’s your favourite part of the life cycle of a book? The inspiration, writing the first draft, revision, the editorial relationship, promotion and discussing the book, or something else altogether? What's the toughest part?

AMJ:

The most exciting part for me is the stage of the first draft when you’re near the end and finally getting to write some of the scenes that tortured your brain long enough to force you to write the book in the first place!

The toughest part is probably the lonely moments when it feels like no one but you cares if this story exists. But I just try to remember that every book I’ve ever loved was once a frustrating first draft that sat like an anchor in someone’s computer.

_________________________________________________

Alexandra Mae Jones is a queer writer based in Toronto. Her short fiction has been published in several literary magazines, and she is a freelance reporter for CTVNews.ca.