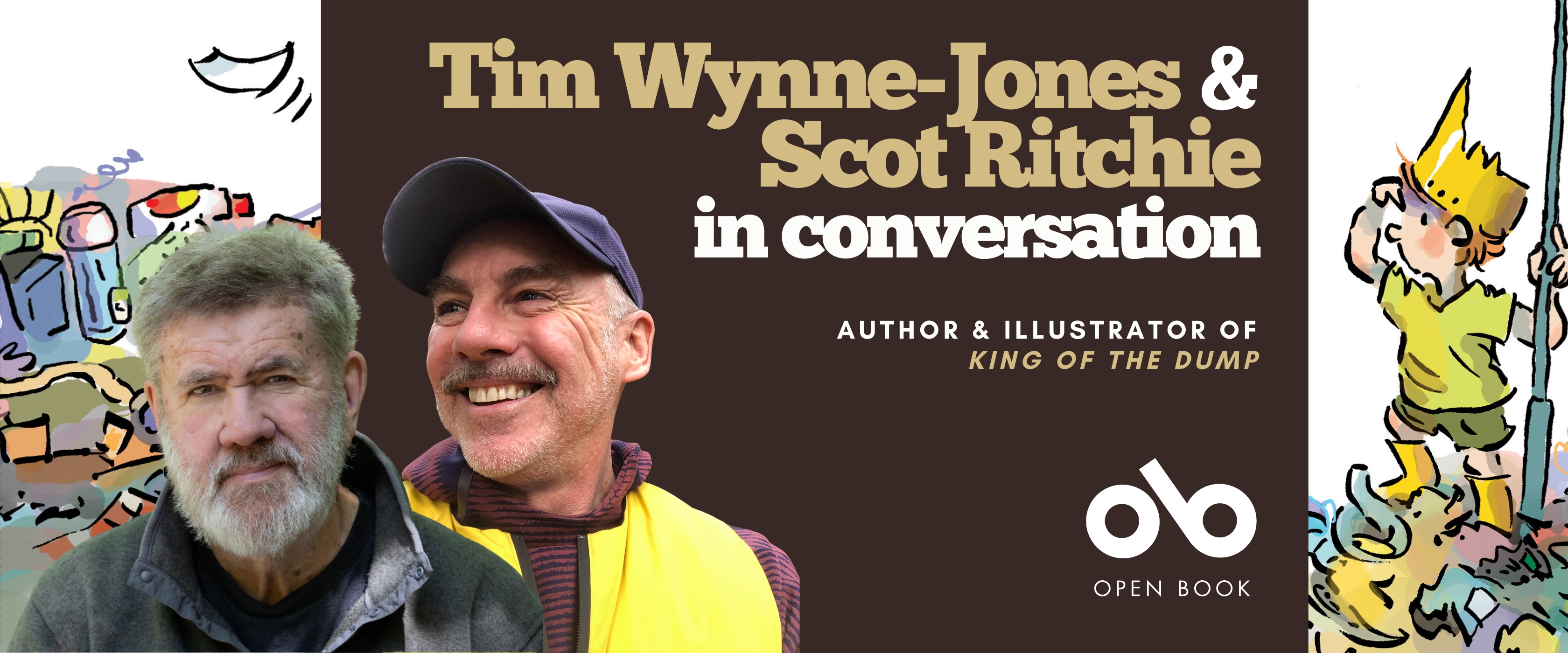

Tim Wynne-Jones and Scot Ritchie in Conversation About Their Brand New Picture Book, King of the Dump

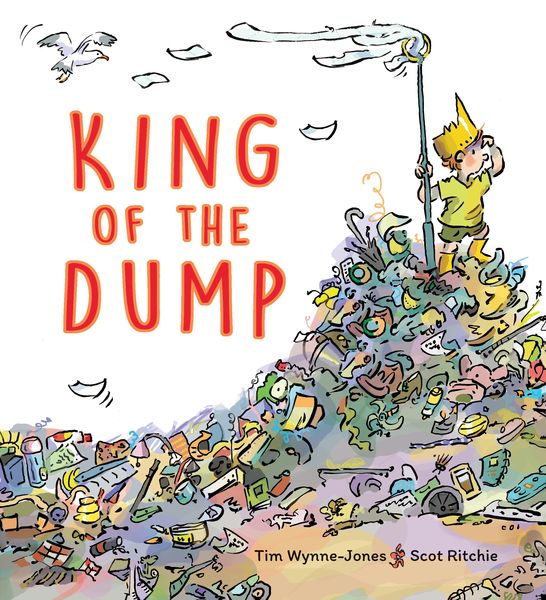

Today we're very excited to feature a new picture book from Tim Wynne-Jones and illustrator Scot Ritchie, two acclaimed and established artists with a long list of unforgettable titles under their belts. Their latest is the eye-catching King of the Dump (Groundwood Books).

In this lively story, we join Teddy and his dad on an epic adventure to the local dump (well, actually, the rural waste management center). There, Teddy finds himself sorting recyclables like a pro, snatching bottles with a garbage claw, chasing runaway paper, and taking in the size and scope of the whole operation as the noisy compactor squishes trash into tiny bundles. Giant machines like forklifts and bulldozers rumble by, stacking mountains of garbage as far as Teddy can see. But, at the end of the big day, it's time to visit the "As is" store to say goodbye to a beloved toy that Teddy has outgrown, if he can bear it...

It's delightful, big-hearted story filled with trucks, trash, and treasures, that celebrates what it means to grow up and let go. And, we're delighted to share a KidLit Convo interview with both creators of this new title, right here on Open Book!

Scot Ritchie:

What was the strangest or most memorable part of creating this book for you?

Tim Wynne-Jones:

The most memorable part of writing King of the Dump was taking my three-year-old grandson to our local waste and recycling centre in Tay Valley Township, Ontario. Felix lives in the city and hadn’t had the pleasure of visiting a real live country garbage dump but I was pretty sure he’d get a kick out of it. I love the place. I’m into sorting things and making sure they go in the right box. I’m just a wee bit anal about that kind of stuff. My grandson liked the dump for completely different reasons: all those big clanking vehicles — trucks and caterpillars, diggers and crushing machines! As I expected, he was in little-kid heaven with all that noisy industry going on around him.

And then there was the recycling shop, chockablock full of all manner of stuff people had thrown out but that still had life in it and, in some cases, miraculously just so happened to be exactly what you were looking for! For a small person, the As Is Store was kind of like Christmas morning without the tree or wrapping paper. The only difficult part was getting the boy out of there with only a few not-so-new toys.

So, the book kind of wrote itself.

The strange thing — well, the ironic thing — came later. A few months before publication date, Tay Valley changed how it recycles, and so, before the book was even on the shelf, much of the early part of the story was no longer what I had portrayed. But the effort was still there, and the story holds, especially the dramatic, and I hope, satisfying conclusion. Reduce, Reuse and Recycle makes for happy endings.

SR:

Do you relate to any of the characters in the book? If so, who and in what ways?

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

TWJ:

Sure. All of them! One of the great joys of being a writer is imagining your way into all sorts of lives. I relate to Teddy, having been a child myself. (At his age I ran away from home with a tea cozy on my head.) Childhood is a renewable resource. I relate to his dad, having been a father three times over. Weighing the emotional turmoil of having to give up a favorite toy, and hoping it’s not going to be too traumatic for your kid. Been there! But I also really enjoyed being Gord, the helpful guy at the dump, and Doris, the resourceful lady in the As Is store. And the couple with their little girl looking for … well, as it turns out, the very riding toy Teddy brought in. I can feel how proud he must be.

SR:

Is there anything you want to tell me about your experience working on this book?

TWJ:

As I said above, the story almost wrote itself. The first draft came easily and then it was only a matter of trimming, trimming, trimming, leaving room for you to bring the whole thing brilliantly to animate life.

Before I ever wrote a book, I was a book designer and, later on, a children’s book editor. So, I have the benefit, I think, of knowing what doesn’t need to be said in a picture book manuscript.

I like to think of a manuscript as a kind of love letter to an unknown artist. I want to charm them. I had never met you before, which is typical of the experience. Publishers usually choose who will illustrate a book and while they may give the author a say in the process, the author certainly isn’t expected to tell the illustrator what to do. Which is as it should be. A playwright doesn’t get to tell an actor how to interpret their words. Everybody’s working towards a singular product but each contributor brings their own training and craft — their inspired sense of what is required.

As a writer, you have to let go of the images you might have had in your head as you wrote and let the artist create what they see in their head. Which means that your manuscript has to woo the artist, intrigue them, leaving enough unsaid for them to want to fill in the blanks. Every illustrator I’ve had the pleasure of working with has added bits of story in their pictures which were not in my words. To me, that is a sure sign that they felt free to explore, to have fun, to expand the story. Reading your own book for the first time in its illustrated state should always be a bit of a discovery.

The difficult author to deal with is the one who can’t let go of any aspect of his or her story. “That’s not how I saw it!” is, I suppose, a reasonable reaction upon seeing the artist’s roughs. And that’s when you hope that you’ve gotten across in the text — and between the lines — what your vision really was well enough that the artist’s contribution builds on the story and makes it more than you conceived without losing the central heart of the thing. I was really lucky to get to work with Scot who made King of the Dump his own and in so doing made it a whole lot more than words can say.

TWJ:

What are the best, and the toughest, parts of collaborating on books, in your opinion?

SR:

Collaborating is the essence of what children’s books are but it occurs in different ways and to different degrees. I have worked with authors in the early stages of writing a story, before a publisher is on board. There is a great freedom at this stage but ultimately your goal is to make a book a publisher wants to print, so you have to be practical too.

The toughest part of the creative process can be when the people involved aren’t on the same page. I’ve had a few books like this over the years (which shall remain nameless). The joy of creation is often dulled here but, looking on the bright side, you are also forced into seeing things from a different angle which I’ve found often turns out to be a good thing — once the grumbling is over. Being a freelance creator requires being able to shift and jump as needed.

By far the most common way to collaborate is to receive the finished story from the publisher. As an illustrator I begin my contribution then. When I received the manuscript for King of the Dump, I was very happy. Tim’s an amazing writer. In this book there isn’t a lot of writing but the location and emotion he invokes was a gift for me. I fell into the story so easily. I also knew I’d be working with an amazing team at Groundwood. One of the best things about making books is that it continues to be fresh each time because it always involves new people. I may like a certain approach, but the publisher, author, art director or editor may like a different approach — and you have to be able to roll with that.

I’m in the middle of a book now where, after sending in my rough illustrations, I discovered that the author had intended something else for a certain spread. In this case, I’m sticking to what I’ve drawn because my illustrations follow their own story arc. It’s important for illustrators to explain why they want to focus on a certain angle of the story or image. For King of the Dump, I received suggestions in the manuscript and found those hugely helpful, but I very much consider this my time to do my half of the book.

TWJ:

What advice would you give to someone working with a co-creator on a book for the first time?

SR:

Respect your co-creators. I’ve done over eighty books (as author/illustrator or illustrator), and each one is different because each story is different and each team is different. There can be bumps along the way, but I am always reminded that there are thousands of illustrators out there who want this gig.

I have two obligations: to do my job (I was hired because the publisher likes my work) and to remember I’m not working alone. Books aren’t too different than movies in that regard. There are less players involved but to make a winning book, each player has to do their bit while listening to the other players. Ultimately the publisher is paying the tab so they decide what direction we go if we’re at an impasse. It’s worth saying that in this business, I’ve found publishers to be very respectful of their creators. For longevity in the business, you want the reputation of being helpful, respectful and knowing how to draw well. I’m aware that a good portion of what makes anyone appealing is their professional attitude.

TWJ:

Is there another co-creator team whose books you find inspiring? (I’m particularly interested in what/who inspired you to become an illustrator.)

SR:

In kids’ books the most famous team is Munsch and Martchenko. We both had the same publisher when we were starting out, Annick Press. Munsch and Martchenko were a bit ahead of me, so I was able to watch their progress. I even did some of their promotional material, drawing a paper bag princess and dragons for their new book’s POP displays. It was fairly humbling, as I was starting out with my own style, to be asked to draw in Mr. Martchenko’s style, but it taught me I could do that and actually increased my self-confidence as an artist.

It was an exciting time as we were all new to the business and learning as we went. I kept an eye on them as my career began but soon realized I needed to focus on my own style if I wanted to be successful. I’ve been hugely inspired looking at books by authors and illustrators I enjoy, but I’ve found focusing on their work to often be more of a distraction than a help.

To find your own voice you have to carve out your own style. An author talks with words and an illustrator talks with images. Studying Renaissance painting, Pacific Island tattoos or cartoons by Tintin or Sempe, can all inform what you do.

Every year that I could afford it I would go to the Bologna Book Fair in Italy to try and drum up business. An extra bonus was that I saw how illustrators in other parts of the world worked — how they would draw face or animals, shading or light. This inspired me, and although not planned, helped my books to sell worldwide.

In terms of what inspired me to illustrate, it was more a case of there not being anything else that interested me as much. Art is the most amazing thing in the world to me and I have always drawn or sketched or painted. I consider myself lucky that every new project I am hired to do continues to excite me.

_________________________________________________

Tim Wynne-Jones is the author of more than 35 books and is a two-time winner of the Governor General's Award, as well as a two-time winner of the Boston Globe–Horn Book Award and of the Arthur Ellis Award. His recent books include War at the Snow White Motel and The Starlight Claim. Tim is the recipient of the Edgar Award, the Vicky Metcalf Award for a Body of Work and is an Officer to the Order of Canada. He lives in Perth, Ontario.

Scot Ritchie is an award-winning illustrator and author with more than seventy books to his credit, including Tug, P'ésk'a and the First Salmon Ceremony, Federica and Owen at the Park. His books have been translated into French, Korean, Indonesian, Polish, Finnish, Arabic and Dutch. Scot has worked with the National Film Board of Canada and has exhibited his illustrations at the National Gallery of Canada. He lives in Vancouver, British Columbia.