L.M. Montgomery, Ontario, and Poetry

By Kate Sutherland

Today I gave a reading from How to Draw a Rhinoceros from the pulpit of the Historic Leaskdale Church, a somewhat unlikely location for my first public reading from this book. The occasion was LMM Day, an annual celebration of L.M. Montgomery organized by the Lucy Maud Montgomery Society of Ontario, the theme of which this year is poetry.

Given that Montgomery was best known for her novels set on Prince Edward Island, you might be wondering what she had to do with Ontario and with poetry. It’s true that all but one of her twenty novels were primarily set on PEI. But most of them were written in Ontario where she lived for three decades. In 1911, at the age of 36 and with four novels under her belt, she married Ewan Macdonald, and moved from PEI to Leaskdale, Ontario where Macdonald was minister of St. Paul’s Presbyterian Church (now the Historic Leaskdale Church). Though she returned to PEI again and again in her writing, she never moved back, living the rest of her life in Ontario, first in Leaskdale (1911-1926), then Norval (1926-1935), and finally Toronto (1935-1942).

Montgomery’s one novel wholly set in Ontario, The Blue Castle, is essentially a love letter to Muskoka, and her journals made clear that she found much else to love in the Ontario landscape. And she thoroughly enjoyed the extensive cultural life she had access to first near and then in Toronto, regularly attending plays and concerts, giving readings, and attending meetings of the various literary organizations with which she was involved. If this part of Montgomery’s life interests you, I recommend dipping into the essay collection L.M. Montgomery’s Rainbow Valleys: The Ontario Years 1911-1942 (I wrote a piece for it on Montgomery’s work with the Canadian Authors Association).

And what of poetry? Montgomery always averred that it was her first love and the genre in which she most enjoyed writing. But fiction paid better, particularly after the success of Anne of Green Gables, and she had to make a living. Only one collection of poems was published in her lifetime, The Watchman and Other Poems in 1916, and she had trouble even arranging that. Her first publisher, L.C. Page, refused the manuscript on the basis that poetry didn’t sell. Their relationship had already deteriorated significantly at this point, but the refusal of her poetry could be regarded as the final straw. They soon parted ways leading to more than a decade of litigation (the subject of a chapter in my book on writers’ lawsuits), and it was McClelland, Goodchild, & Stewart who published The Watchman and became the Canadian publisher of all of Montgomery’s books thereafter.

Poetry was chosen as the theme of LMM Day in Leaskdale because this year is the centenary of the publication of that book of poems, and I was honoured to be invited to read from my first book of poems as part of the celebration. My poetry aesthetic is very different from Montgomery’s, and given the rarity of The Watchman, I didn’t get the opportunity to read many of her poems until quite recently. But I count her as a formative influence nonetheless and said so before launching into my reading.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

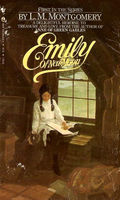

It was not Montgomery’s poems that influenced me, but her depiction of the writing of poems in her fiction, particularly in Emily of New Moon. Much of that novel is devoted to tracking Emily’s development as a writer from the moment when, aged eleven, she realizes that she can write poems. She weathers the disapproval of her guardian and the ridicule of some of her schoolfellows and a teacher. She is buoyed by occasional moments of validation. But mostly she just keeps writing because she loves to, because she can’t not. She experiences flashes of inspiration and feverish writing sprees. But she also works hard to improve. She reads all of the poems that she can get her hands on. She begins to figure out what makes one poem better than another. She keeps revisiting her own precious pile of manuscripts and reassessing them, recognizing that some poems she though wonderful scant months ago aren’t, indeed that some of them are downright silly. Eventually she finds a mentor, and heeds his message that if at thirteen she can write ten good lines out of 400, at twenty she might be able to write 100 good lines. But she’ll have to work hard and sacrifice to develop her art. All helpful messages to me too when I read and reread Emily of New Moon long ago as an adolescent aspiring writer.

And so I tip my hat to L.M. Montgomery on the occasion of the publication of my own first book of poems, and the centenary of the publication of hers.

The views expressed in the Writer-in-Residence blogs are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Kate Sutherland was born in Scotland, grew up in Saskatchewan, and now lives in Toronto, where she is a professor at Osgoode Hall Law School. She is the author of two collections of short stories: Summer Reading (winner of a Saskatchewan Book Award for Best First Book) and All In Together Girls. How to Draw a Rhinoceros is Sutherland’s first collection of poems.

You can reach Kate throughout the month of October at writer@open-book.ca.