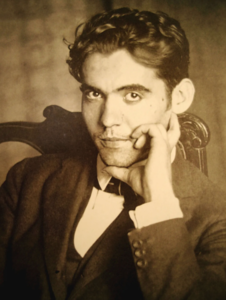

On Federico García Lorca's "Duende"

By Martha Bátiz

What immediate need of yours has to be satisfied before you can hit the keyboard? If I had to have a clean house before I sat down to write, I would never have written anything after I got married and became a mother. Having three children, two dogs and two cats (plus a husband) means that my surroundings are fully lived-in, and it shows. I have learned to make peace with that. A decently tidy desk, beds that are made, dinner cooking in the crock pot or consensus on what kind of take-out will be enjoyed for dinner are my basic requirements in order to peacefully occupy my chair in front of the computer. Other writers need to have a drink at hand, be in their slippers, or munch on potato chips. But that is only the beginning.

Do you write every day so that, as Picasso famously said, inspiration finds you working? Or do you patiently wait until the proverbial Muse descends from above and gently nudges you into action? Every writer approaches their work differently. The mental, emotional, and physical efforts behind a writer’s work are seldom appreciated, that is, unless a books sells well. Then people clamour to find out the magic formula behind such feat. But, as my godmother used to say, there is no magic: success is nothing more than very hard work disguised as good luck.

I grew up being very aware of what that kind of hard work looked like. My parents were both child prodigies. By the age of 10, my mother had already played a full concerto as a soloist with the Caracas Symphony Orchestra. At 13, she had graduated from Venezuela’s Conservatory and, at 14, on the recommendation of Arthur Rubinstein himself, she received a full scholarship to attend the prestigious Juilliard School of Music where she successfully completed her Bachelor’s and Master’s Degree in piano. It was there that she met my father who had followed a similar path to New York (sans Rubinstein) from his native Mexico. I know by heart those stories about how they survived on their own —on very tight budgets, and at so young an age— in the New York of the early sixties. They were talented, no doubt, but they also invested six to eight hours a day in their craft, sometimes more, by playing the piano, memorizing scores, or studying the great masters’ recordings and interviews. And while they did refer to Euterpe, the Muse of music, “giver of much delight” at home, I also heard about “duende.”

Duende means “elf,” “goblin,” or “leprechaun,” but Spanish poet Federico García Lorca used this term to describe “a momentary burst of inspiration, the blush of all that is truly alive, all that the performer is creating at a certain moment.” (García Lorca, Federico: In Search of Duende. New York: New Directions Books, 1999: viii) Duende is that spark, that divine and miraculous presence which becomes palpable when an artist’s performance on stage is entrancing.

No emotion is possible unless the duende comes, says Lorca. And unfortunately, “…there are neither maps nor exercises to help us find the duende. We only know that he burns the blood […], that he exhausts […], that he leans on human pain with no consolation.” (60) In short, and as I understand it: the duende is an inspirational force that wounds. That wound, in turn, never closes. And it is the attempt at healing said wound that produces an artist’s best performances. Duende is gift that cannot be summoned, but when it shows up on stage its light burns bright as fire.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

How does this apply to writing? I’ve been trying to figure it out for years. We don’t perform on stage, but many of us certainly have a fair amount of pain to work with, and portray that pain through our characters who, in turn, are on stage in front of the reader’s eyes. And the most powerful characters, those who stay with us long after we have closed a book, all have duende. Think about it for a moment. You’ll see I’m right. Forgive me, I must rephrase: Lorca was right.

No one can decide, late in life, that they want to become an opera singer, or a concert pianist, and be successful. Certain artistic disciplines have to be pursued since childhood, or from a young age, with complete dedication and devotion. But human beings have been practicing storytelling since the dawn of civilization. We tell stories to our children, to our parents, to our friends. We choose our words in order to attract their attention and, if possible, charm them. We repeat our family’s stories —how we ended up living here, which one of our ancestors fought in the war, or escaped occupation, or saved or lost the crops, and what happened next. We repeat our own stories —how we fell in love with someone, or had our heart broken; the time we rose to a particularly difficult challenge or had our most painful defeat. Everyone has been practicing to be a story teller all their lives, and while some people are more effective at it than others, the truth is that we, as a species, are all writers in rehearsal. And it is never too late to sit down and tell our stories in writing if we so wish. Literature is very generous that way, but it will still demand a lot of hard work and effort —and even pain, perhaps, especially if we are to write about what truly matter to us.

Allow me to reintroduce my opening questions: what propels you to write? Do you write every day?

It would be a dream for me to be able to write every day, but the truth is, I don’t. Life is too complicated when juggling a job, mothering, homemaking (all those endless chores!), commuting. I’ve made peace with my own limitations. As I go about my daily responsibilities, however, my mind is busy playing with different scenarios and characters until I find one whose ingredients slowly simmer and brew inside me until writing about them becomes a physical necessity. I have to sit down and let this character and its circumstances out because, otherwise, it hurts. When I finally sit down to write, I do so for long hours and with my senses fully open, welcoming all the emotions that stem from the process. In my case, it hurts to write, but it would hurt much more not to. Plus, I know duende likes to sit right at the edge of pain and, to be honest, his blade appeals to me way more than the gentle touch of any Muse.

The views expressed in the Writer-in-Residence blogs are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Martha Bátiz is an award-winning writer, translator, and professor of Spanish language in literature. She is the author of four books, including the story collection Plaza Requiem, winner of an International Latino Book Award, and the novella The Wolf’s Mouth, winner of the Casa de Teatro Prize. Her most recent publication is the story collection No Stars in the Sky (House of Anansi). Born and raised in Mexico City, she lives in Toronto.