Natasha Ramoutar: On Full Circles and First Books

By Sheniz Janmohamed

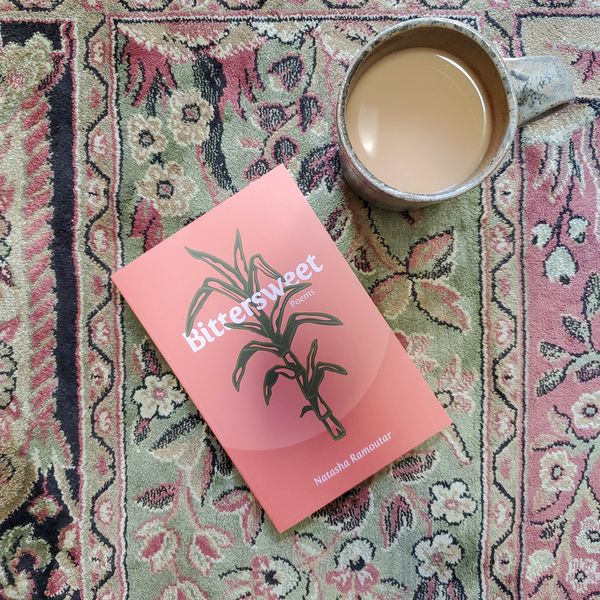

Less than a month ago, Natasha Ramoutar published Bittersweet, her first book of poems, with Mawenzi House. Less than a month ago, I celebrated the ten year publishing anniversary of my first book, Bleeding Light, also published by Mawenzi House. Natasha happens to be my mentee, and it has truly been a serendipitous full circle to mark my anniversary while celebrating her first steps into the world of being a published author. I recall, with fondness, the hours we spent organizing her poems on my sitting room floor, taking sips of homemade chai between edits. It brought me back to the time I sat with my mentor, the late Kuldip Gill, at an Indian buffet, where we brainstormed refrains for my first collection of ghazals. When Natasha asked me to mentor her, questions arose about my own experiences of being mentored: What did I need? What can I offer? How will this be different? What is the point if I don’t learn as much as I impart?

Through my mentorship with Natasha, I’ve been reminded of the discipline, courage and faith it takes to write. Through her passion to complete her work, I was given the opportunity to be held accountable for completing my own work. She has brought me back to the reasons why I began to write.

So, in light of the wonderful reciprocity we share, I invited Natasha to chat with me about full circles and first books.

SJ:

What does it feel like to finally have your book in your hands?

NR:

It’s really surreal. At times, it’s hard for me to believe that this collection went from being a bunch of unorganised Google Docs to this real, physical book. The cover was designed by my friend Sarah Lacasse which is really special to me. I was also so excited to put the book alongside my Scarborough peers on my bookshelf - next to Adrian De Leon’s Rouge, Téa Mutonji’s Shut Up, You’re Pretty, and Oubah Osman’s Hereditary Blue.

SJ:

What does it mean for you to all come up together, to be Scarborough writers? How has that impacted your writing/aesthetic?

NR:

Coming up together has been (and continues to be) a real delight. The writing world can often feel like a very competitive and intimidating space because of the business side of publishing and because of awards. I also feel like we’re often fed a myth of scarcity - that there are limited resources available for writers.

I feel really grateful to have my friends and fellow writers from Scarborough who unconditionally support each other. We celebrate everyone’s achievements. We offer feedback on each other’s writing. Before the pandemic, we would attend each other’s events. When we would go to these events, we would show up loudly for each other. It felt like we all gave each other permission to collectively claim that space.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

We do our best to make space for each other and for other Scarborough writers, which is a part of what Téa, Adrian and I are trying to do with our anthology FEEL WAYS and with any events or installations we can curate. I know that I just mentioned the “myth of scarcity,” but the arts scene in Scarborough (like many pockets across Toronto) did genuinely have a lack of resources for years. Now that we have funding and a spotlight on artists in this suburb, I feel that many collectives and arts leaders are trying to make programs or spaces so that the next generation has it easier.

We all write with very different styles and work in different genres. I haven’t felt that their feedback has drastically changed anything with my aesthetic or writing. Instead, they’re often able to bring out my best writing with their line edits and tighten up my writing. I’ve learned to lean into my voice or style more with their help.

SJ:

Where/when did the idea for Bittersweet take root in your heart/mind?

NR:

The idea for Bittersweet was a bit of an accident. I had been writing poetry for a number of years while I was a student at the University of Toronto Scarborough (UTSC), but I hadn’t shown the work to anyone. In 2017, I realized I had written a significant number of pieces as I organized and revisited my work. When I reread the pieces, I realized that there were several themes I had naturally gravitated towards. Working with you during our mentorship allowed me to consider what type of story I wanted to tell with the collection and allowed me to curate it in a certain way.

SJ:

I’m so glad you came to me with your beautiful poems.

What were some of the challenges you faced in getting the book to this stage? Where did you face barriers on your journey?

NR:

I was my own worst enemy when it came to getting the book to this stage. Although I had the privilege of taking creative writing classes at the UTSC, I didn’t have any formal training in poetry. I read a lot of poetry and I was surrounded by poets, but I constantly questioned whether I was “allowed” to take that title. I would often return to individual pieces and think that they weren’t worth anything, and then they would get shelved again. Working with you really changed my mindset around claiming that space.

That being said, it’s also important to acknowledge that this kind of imposter syndrome is fuelled by gatekeepers and barriers in the literary world who didn’t celebrate marginalized voices. We’re thankfully seeing a shift now with advocacy and work by organizations like the Festival of Literary Diversity and BIPOC in Publishing Canada.

NR:

In an interview with Contemporary Verse 2 for their Emergence issue, you mentioned that some of the concerns of your mentees were your concerns when you were starting out. How do you feel about this and how does it inform your approach to mentorship?

SJ:

The scarcity mindset was alive and well back then, particularly because we didn’t see as many BIPOC writers in mainstream CanLit spaces. It was challenging to write and perform pieces about my identity without my voice becoming a sole representation for my community.

Interestingly enough, in talking to younger/new writers, I find that this is still a challenge. We are in more spaces, yes, but sometimes we’re the only ones from our community/background/faith tradition/gender identity in CanLit spaces.

The fact that this is still a reality is absurd to me.

I’ve been dealing with this for a while, and over time I’ve become more confident in writing what I want to write. What interests me. When I first started out, there was a feeling that I owed my community something, and that my work may not have been literary enough for the predominantly white gatekeepers of CanLit. While I am still deeply influenced by my culture and community, and while there are still gatekeepers in CanLit, I don’t hold myself to the same kind of pressure.

Giving mentees the validation that I needed when I started out-- that their voices are enough-- they don’t have to put the weight of representation on their shoulders-- that craft matters just as much as content-- perhaps this what I’m able to offer in mentorship.

SJ:

What helped you overcome or work through your barriers?

NR:

As mentioned earlier, our mentorship was a big reason why I was able to work through those barriers. Our frank conversations around the state of publishing gave me insight as to where some of these feelings stemmed from.

Beyond this, fellow Scarborough writers have always helped me find value in my own writing (as I mentioned earlier). I’m lucky to have friends like Adrian De Leon, Téa Mutonji, Leanne Toshiko Simpson, Oubah Osman and Chelsea La Vecchia. We’re constantly supporting and sharing each other’s work and are often first readers for each other. If one of us is feeling down about our writing, the rest of us will hype that person up.

NR:

In previous conversations, we've discussed this importance of peer-to-peer support in addition to mentorship. I wanted to ask you how peer-to-peer affected the creation and release of your two books of poetry? How does it continue to play a role in your writing process today?

SJ:

My first book was written during my time at Guelph-Humber, so my peers did provide feedback on some of my poems, particularly in the workshopping classes. It was important for me to have that, because while mentors are vital, so are peers. Peers understand the generational gist of your writing in a way that mentors may not. Your peers are struggling and celebrating in similar ways.

I have peers who I check in with on a monthly or bi-monthly basis, and we discuss everything from craft to the promotion of our work. We source opportunities for each other, provide support and feedback, and hold space for the kind of work we want to create or are creating.

Peers know where you’re coming from and it’s like having a shorthand language between you. You don’t have to explain yourself or defend your choices-- you receive the critical eye you need with the support you deserve.

SJ:

I find that the beauty of the first book is that you’re introducing yourself to a new readership, you get to determine how you debut— there is no expectation of staying within a specific aesthetic you’ve become known for— do you agree/what are your thoughts?

NR:

I agree to an extent. I think that in general, you are introducing yourself to a new readership and that most readers don’t have any expectations. At the same time, if you’ve published in certain literary journals or had worked displayed in exhibitions, there is already a precedent that people in those communities might expect.

I also think that introductions can feel terribly heavy. It’s exciting to have no pre-established style for readers to expect, but there’s also a pressure to carve out space for yourself with your first book. It’s scary to think that a debut might set the tone for the rest of your career, especially knowing that many authors are continuously exploring new ways of writing. One thing I worry about with debuts is that authors might get boxed into one label or style of writing and feel that pressure when working on subsequent projects.

NR:

Do any of these thoughts resonate with the way you felt about your debut?

SJ:

I completely understand the fear of being compared to your first book in terms of style, tone and aesthetic. My first book was an intentional nod to the ancestors of the form I was writing in. I felt that I had to pay homage in that first collection-- firm footing as it were. My views and beliefs have changed considerably since my first book. There are some poems that are too painful for me to read. Some adhere to ways of thinking that are outdated. Some things remain the same. I still write in the ghazal form.

I think it’s important to remember that the book you write at the time you write it is a snapshot of who you are at that moment. If you are evolving and growing, then you may change. Your books may change. Your style, content and aesthetic may change.

As long as you don’t box yourself in, people will have to adapt to the person you are becoming-- through your writing.

SJ:

So why did you go with Mawenzi House?

NR:

Finding a press that had a history of supporting BIPOC writers was important to me, and Mawenzi House has such an excellent track record. I had also spoken to both you and Adrian De Leon about your experiences with the press and was delighted that you two felt valued and cared for during the process. I needed a publishing house that I could trust with the editing and marketing of my work. During the editing process, the feedback I received was craft-based and the editor didn’t question my experiences.

SJ:

Can you recommend a poem from Bittersweet that is a current favourite, or perhaps one that speaks to the times we’re in?

NR:

“Like Makeshift Crowns” is one of my favourite poems in the collection. It doesn’t speak to the time we’re in, but it tries to distill a moment of joy from the past. It’s a celebration of friendship.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Sheniz Janmohamed was born and raised in Tkaronto with ancestral ties to Kenya and India. She has an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Guelph and an Artist Educator Mentor certificate from the Royal Conservatory. A poet, nature artist and arts educator, she regularly visits schools and community organizations to teach and perform. Her nature art has been featured across Turtle Island, including the National Arts Centre and the Art Gallery of Mississauga. She has performed her work in venues across the world and has three poetry collections Bleeding Light (2010), Firesmoke (2014) and Reminders on the Path (2021). She recently served as the Writer-in-Residence at the University of Toronto Scarborough Campus and is the founder of Owning our Stories, the first writing circle of its kind for South Asian women in Ontario.