Publishers and Awards

By Dory Cerny

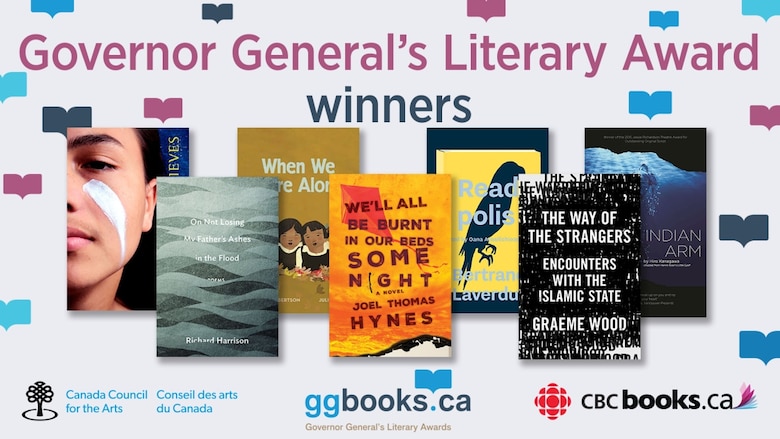

Though fall isn’t quite as busy a time for children’s literature awards as it is for the adult side of CanLit, the two most prominent prizes, the Governor General’s Literary Awards for text and illustration and the Canadian Children’s Book Centre Awards – including the coveted $30,000 TD Canadian Children’s Literature Award – were handed out in November. Now that the frenzy of the book award season is behind us, I thought it might be fun to talk to publishers about what awards and reading programs like the Ontario Library Association’s Forest of Reading mean to business. After all, the benefits to award-winning authors are clear enough: prize money, media coverage for their books and themselves, and a reputation that will serve them well in getting more of their work published, to name a few. But what of their publishers?

A big win is delightful, of course, and all of the publishers I spoke to said that first and foremost what they feel is pride in their authors and everyone who played a part in bringing the book to fruition. But once the Champagne (all right let’s be realistic, this is Canadian kidlit) sparkling wine has been downed and the hugs exchanged, the hard work of using the prize begins.

“We don’t often get money for an award, and when we do, the money is earmarked for promotion, so the best practical result of an award would be from sales,” says Dancing Cat Books’ Barry Jowett. “People assume that a prominent award like the Governor General’s Literary Award will turn a book into a cash cow, but it can’t sell a book on its own. When you look at the sales of GG nominees and winners, the award seems to have very little impact. But that doesn’t mean a GG nomination or win can’t sell books – you just can’t rely on the award to do its own magic. You have to work the award.”

Working the award can take various forms, but Jowett gives a couple of recent examples, including using the GG nomination of Deborah Kerbel’s Under the Moon a few years ago to fuel a promotion with schools, and working with sales reps to get more copies of Cherie Dimaline’s The Marrow Thieves into stores after its spot on the GG shortlist was announced. (It ultimately won.)

At Kids Can Press, Lisa Lyons Johnston says that a big win or even nomination sets off a protocol that includes checking inventory levels, creating new marketing materials, and alerting sales reps that a book has some additional selling features. The company also uses social media to spread the word, and even shares the news with parent company Corus Entertainment’s 2,000 employees via weekly newsletters produced by corporate communications.

Though winning an award might not guarantee a huge uptick in units sold, that lovely, shiny sticker on the cover will catch the eye of the grandparent looking for something to win over a hard-to-please tween or of the friend who is willing to be tempted away from Love You Forever when shopping for a baby shower gift. In other words, someone who knows nothing about kids’ books will gravitate to the stacks on the “Award Winners” table at Indigo, and that’s a sale the book might not have gotten otherwise.

Though the GGs might be the most glamorous and the TD Award the most lucrative for the author, according to publishers nothing beats the Forest of Reading for measurable impact on sales. “When you get on a Forest list, your sales spike by the thousands for the younger ages, and about a thousand for high schools,” says Jowett. Margie Wolfe of Second Story Press echoes this sentiment: “In Ontario particularly, we ship thousands of copies of the Blue Spruce and the Silver Birch books the day the nominees are announced. You don’t even have to win to win!”

We know that the school and library market are the backbone of children’s publishing in this country, so getting a title (or several across categories, if you’re lucky) into Forest of Reading is a huge boon, and can make a big difference to the bottom line. But more than that, the fact that the awards are decided by kids is meaningful to both publishers and creators. “We reach a wide audience of readers, which is so valued,” says Rick Wilks of Annick Press. “And both the publisher and author are financially rewarded for producing a publication that is embraced by youth. The Forest of Reading is to be commended for developing such a successful model.”

Beyond sales, awards bestow upon a publisher a certain level of credence. Having sat on a couple of juries in my day, I can honestly say that books with low production value, bad art (not just illustrations that weren’t to my taste, but bad art), or typos were almost immediately out of the running. The books that make it to shortlists aren’t there on the merit of story alone; we do judge the editing and yes, even the covers. The benefits of award-related cachet is twofold: not only does a track record of publishing award winners attract a higher calibre of creators, Wolfe notes it’s also useful on the rights front. “When I try to sell rights, many foreign publishers value prizewinners particularly and will sometimes print the Canadian award sticker on their foreign editions,” she explains.

It’s hard to argue with the value of recognition from the U.S. and, to a lesser extent, Europe. The reaction when Dimaline took home the $25,000 GG for The Marrow Thieves was expeditious and encouraging, but paled in comparison to the attention the author received when it was announced she’d also won the $50,000 (U.S.) Kirkus Prize. The double-whammy win for the book, a debut YA novel by an established Indigenous author set in a dystopian Canada of the not-so-distant future, sent book media here and in the U.S. into a tizzy. Which is great, of course, and well deserved, but it begs the question of why we still value recognition from outside our own borders more than we do within them.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

Perhaps part of it, as mentioned to me by a few publishers, is that we still don’t quite have a handle on celebrating YA in this country. Other than the GG, OLA’s White Pine, and the CCBC’s Amy Mathers Teen Book Award, most awards tend to focus on books for readers under 12 and, as Jowett laments, YA isn’t eligible for most “adult” awards either, meaning there’s a much smaller potential for really good books geared to teens to win awards, which translates to less promotion and fewer opportunities for authors to get noticed and, ultimately, make a living.

A similar conundrum exists for non-fiction. There’s the Norma Fleck, the Lane Anderson, and the Silver Birch, but comparing a biography for tweens to a STEM-based picture book on engineering to a title full of facts about bugs feels unfairly imprecise (trust me, I’ve done this). “It seems wrong for “information” books to be in the same mix as “narrative non-fiction,” says Wolfe. “I would create separate award categories.” And, given the way that books for young readers have shifted in tone, Wilks wishes for a prize that recognizes books that promote social justice, a category that is underrepresented among award winners.

The upshot is that while there are certainly a good number of awards in this country, there is room for more. After all, publishers love them.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Dory Cerny is a writer and editor living in Toronto. Before her recent return to the freelance life, she was the Books for Young People editor at Quill & Quire for six years. In addition to writing about the Canadian book scene and reviewing fiction, non-fiction, and kidlit for Q&Q, Dory also contributes book-related writing to The Humber Literary Review, The Hamilton Review of Books, Canadian Children’s Book News, and CBC.ca.