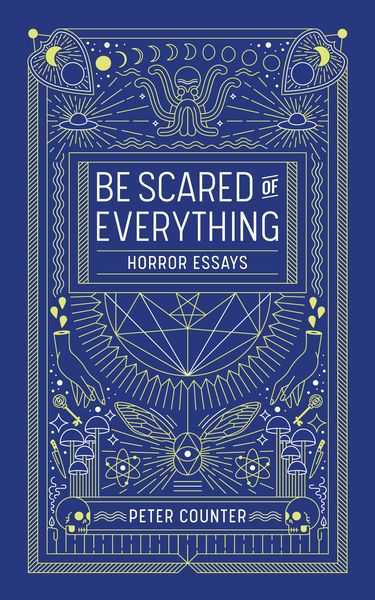

Book Therapy: Peter Counter’s Be Scared of Everything

By Stacey May Fowles

“Life is all we have and, because we can’t contrast our experience with its absence, its value is unknowable. That’s what makes life a horror show.”

—Peter Counter, Be Scared of Everything

Lately I’ve been having this recurring nightmare, particularly upsetting because of how true to life it feels. The dream features a pretty accurate facsimile of my bedroom and upstairs hallway, while the familiar sound of my daughter’s white noise machine drones away in the background, and our old grey cat sleeps curled up at the end of the bed. The pale light from the bedroom window illuminates the doorway, creating ominous shadows that creep all the way down the hall.

And then there is the man.

Dressed in an oversized army green raincoat, he stands just outside my daughter’s bedroom. His hood is pulled up over his head, partially covering his face, and he holds an indiscernible but obviously heavy object in his right hand. He stands there in the hallway motionless, rain dripping from his body and pooling at his feet, an imposing statue threatening the unspeakable.

He takes a step forward and I wake up.

Sometimes this dream feels so real that I will actually get out of bed and check to make sure all the windows and doors are securely locked. (They always are, of course, but I have to check.) After his late night visit it can sometimes take hours for me to get back to sleep—every errant sound from the floor below is, in my exhausted mind, that skulking stranger in the army green raincoat. If I let my guard down even for a moment, that’s when he will make is move.

I sleep with the bathroom light on. I pull the covers over my head. I seek reassurance like a toddler in footie pyjamas terrified of whatever monster lurks in the darkness of her closet. Even though I know, rationally, all of this is pretty absurd, the vision of him persists whether I am sleeping or awake—soaking and still, his mysterious weapon of choice clutched tight and heavy in his right hand.

As much as I am a therapy evangelist, I don’t think I need an hour long session to figure out what this dream is really about. A mysterious threat lurking in the shadows, looking for a way into the safety of my home, ready to harm my family at any moment? That feels like a pretty on the nose pandemic metaphor if I’ve ever heard one. Surely my anxious mind has manufactured this man in the army green raincoat, a faceless nighttime visitor to stand in for my real world worries—the kind I have and try to suppress every morning when I send my daughter off to preschool.

Horror, whether in our pandemic-induced anxiety dreams or on our small and big screens, is really all about working through things. My personal obsession with the likes of Halloween, Hannibal, Night of the Living Dead, or even the ripped-from-the-headlines horribleness that is Law and Order SVU (dun dun) is more about what I need to process about the world than what is actually happening in the plot du jour. When I see Laurie Strode attempt to defeat a menacing Michael Myers with little more than a coat hanger, I have renewed faith I can actually be the final girl in my own personal horror show. I can temporarily suspend my disbelief in myself.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

“Sometimes the world feels made of train tracks,” Peter Counter writes in his new essay collection, Be Scared of Everything. “A planet sized rubber band ball of iron, spikes, and wood, devilish engines, chugga-chugga-chugging along. Each of us anticipating the moment that distant whistle becomes a rumble, becomes obliterating locomotion, becomes our timely end. There is no escape from suffering, even behind closed eyes. There is only the wait.”

And because there is no real escape from suffering, no way to know if or how or when it is coming for us, when exactly it will take a step forward, we must find a way to cope. We must find safe ways of looking directly at the things we fear the most, if only so they won’t destroy us.

Part memoir, part criticism, Be Scared of Everything smartly asserts that our love of being terrified is certainly not to be taken lightly. Aliens, zombies, homicidal maniacs, man-eating sharks, haunted houses—they all help us unpack and explore who we are, where we’re at, and what we need to get through. Like voices summoned on a Ouija board, they give us what we’re subconsciously seeking, the answers we didn’t know we needed.

Counter uses his own history of trauma to explore how horror can actually be deeply healing, the genre generously stewarding us through what scares us the most to a place of actual acceptance. “Scary movies gave me something else to have nightmares about,” he writes of his own journey, crediting his submersion as a way of coping with a terrible event and its subsequent effects.

An essay about Hannibal, for example, asserts that the television show’s glamorous (if thoroughly blood-soaked) terror acts as a balm for those who, like himself, suffer from PTSD. Its unfolding drama subtly normalizes the hyper-arousal and ever-present fear that comes along with the all too common diagnosis, making the show so much more than a mere over-the-top gore-fest about a sophisticated cannibal with excellent taste.

Counter’s in-depth discussion of a hypothetical Zombie apocalypse actually feels painfully applicable to our current pandemic lot; “It only takes a few minutes to realize that survival is about creatively cooperating to make the best of the worst possible situation.” In discussing what each of us might bring to a battle against the shuffling, undead hoards, we have the potential to learn about what we are capable of, and how we might cope with strife.

“By treating the zombie apocalypse as real in our conversations, we tacitly give ourselves permission to associate real disasters like bombings and climate change and economic collapse with fiction.”

And that is precisely the point—despite the keep-you-up-at-night scares, the fiction of horror actually makes us feel safer. We pop our popcorn, settle in on the couch, and embrace the genuine cathartic scream we’re so desperate for. We court the necessary release and relish in the tidy closure narrative generally brings. We get the renewed perspective we’re seeking (I mean, it’s a low bar, but at least this isn’t Dawn of the Dead?) Filmic horror provides a shot of strength to endure the horror that is real life, however unrelated it may seem on the surface.

Ultimately it buoys and inspires us to see people strive for survival in the worst of possible circumstances. There is something very human about wanting to see people hang on so desperately, to fight their way into the light as the darkness seeps in.

As Counter so aptly puts it, “(N)othing says ‘I love life’ like desperately clinging to it as you hide, cry, and bleed.”

So often painted with a derisive brush, the horror genre is commonly dismissed as morbid, or profane, or even meaningless. But I would argue—and I assume Counter would agree with me—that despite all the rampant death and destruction, horror is actually a way to celebrate human perseverance, resilience, and existence itself. I am afraid of the man in the army green raincoat precisely because I am lucky enough to feel safe, to feel loved, to have been given something worth protecting from harm. I am afraid because the threat hasn’t arrived yet. I am afraid because I am grateful that I live.

Be Scared of Everything successfully conveys that horror is much more than trashy escapism, and that a good scare is not always just a cheap thrill. Entertaining ourselves via what we recoil from is often a viable way to safely—and even therapeutically—swim in real life terror writ large. It’s a way to endure and soothe our real world anxieties, looking directly at them while comfortably looking at a screen. It’s a way to celebrate being alive.

This Halloween night, I’ll prepare some of my favourite snacks, wrap myself in a cozy blanket, and settle in for a good scare. Maybe something about a group of surly teens confronting an unknown mad man, or a family terrorized by a creepy dilapidated house and all its dark secrets, or a supernatural monster-type villain pulled from the depths of hell. Though it could be argued I’m fuelling the nightmares by filling up on horror classics, I prefer to think I’m purging myself of the rampant real world anxiety that conjured them in the first place, thankful for the safety on this side of the screen.

If teenage babysitter Laurie Strode can successfully subdue her relentless monster, if Sidney Prescott can lift the mask off a knife-wielding Ghostface, if Martin Brody can dramatically blow up a man-eating shark—then surely we can quell what stalks our minds at night. Surely we can face what terrifies us.

Book Therapy is a monthly column about how books have the capacity to help, heal, and change our lives for the better.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Stacey May Fowles is an award-winning journalist, novelist, and essayist whose bylines include The Globe and Mail, The National Post, BuzzFeed, Elle, Toronto Life, The Walrus, Vice, Hazlitt, Quill and Quire, and others. She is the author of the bestselling non-fiction collection Baseball Life Advice (McClelland and Stewart), and the co-editor of the recent anthology Whatever Gets You Through (Greystone).