Book Therapy: Sunny Days Inside

By Stacey May Fowles

“Is it safe?” “It’s safe now but when won’t it be safe?” “It’s not actually bad here.” “It’s not bad there either.” “What about the money.” “But what about the kids? They’ll be so disappointed.” “Should we go? “If it’s safe we should.”

—Caroline Adderson, Sunny Days Inside

One very cold weekday in late January I was out for a walk and ran into a friend. Standing six feet apart on the sidewalk, she and I exchanged the usual pleasantries, made the usual small talk, and then dove head first into complaints about pandemic living. A mother of two, she let me know her family had just recovered from a household-wide COVID diagnosis and had emerged relatively unscathed—if you didn’t count being existentially upended and completely exhausted.

“We’re doing okay,” she told me. “But the idea of what our kids have been missing out on is keeping me up at night.”

She went on to compile a list of things that were triggering her insomnia—maybe kids are falling behind, maybe all the countless cancellations will threaten their ability to swim or play the piano or become professional athletes, maybe years later they’ll find it hard to meet new people or chat at parties. Some of this was just casual banter, but as the list grew, a shadow passed over her face, like she was carrying the weight of what had been taken.

“Don’t go down that road,” I remember telling her. “It doesn’t help."

“I can’t stop myself. I just lie in bed and think about what they’ve missed out on. I mean, your daughter should be over at my house right now, playing with my kids.”

In the moment, I knew any reassurances I could offer would ring false. Of course I thought constantly about what children have been deprived of. Of course I thought about what the ramifications of that loss will be. I too had fear, and frustration, and anxieties, the kind that other people had told me to put out of my mind.

Early in the pandemic, when my daughter had just turned two and we had settled into our new locked down reality, a lot of people said, “don’t worry, children are resilient.” It was a phrase used over and over again by friends and colleagues, by my daughter’s grandparents (that she wasn’t allowed to visit,) by experts on television and in newspaper articles. I think I may have actually been buoyed by the sentiment at the time, watching my toddler laugh, play, and find joy in what I thought was misery, watching her marvel at the latest subpar craft project I’d put together, or the baking soda and vinegar experiment I had managed to scrounge up. I appreciated her ability to live in the moment, especially when I only felt capable of refreshing my news feed and obsessively looking up case counts.

“Children are resilient” was an idea I clung to desperately for a very long time, when the weeks and months dragged on and I started to tally up all of those things my daughter wasn’t experiencing—preschool, playdates, playgrounds, toy stores, restaurants, relatives, travel, the museum, the zoo, on and on and on. “Children are resilient” felt believable because, to be honest, she seemed to be handling the limitations of her world so much better than I was.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

But two years later, the idea that “children are resilient” doesn’t help all that much anymore.

In the author’s note of Sunny Days Inside, Caroline Adderson refers directly to that famous resilience. She writes of children’s ingenuity during a deeply terrifying time, and of her intention for the book to be “a tribute to children the world over.”

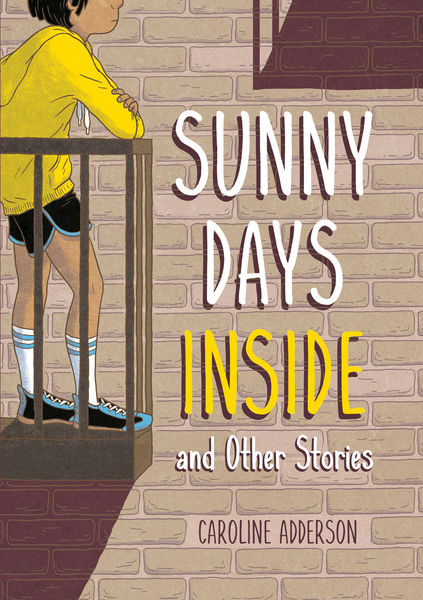

A collection of linked stories for middle grade readers, Sunny Days Inside thoughtfully depicts the lives of a group of kids in a single apartment building during the early pandemic days. (“The safest thing to do was to be afraid of everybody.”) Faced with a “grownup virus” and being severed from the people and things they love, we see how each family is effected, and how they cope.

“They were talking about the virus and how it was spreading so fast. Some families cancelled their holidays. There was a rumour that school wouldn’t start again after the break. The grown-ups talked in whispers so that the kids wouldn’t hear. But the kids heard them anyway.”

The collection depicts how children—despite their own fear, frustration, and anxiety—find ways to make the best of what they are given. A family cancels a much-anticipated trip to Mexico and decides to stage a resort-style vacation inside their apartment (complete with fruity drinks and ocean sounds.) A young entrepreneur rents out his dog to neighbours who need a sanctioned reason to go for a walk. An aspiring athlete risks having his dreams stolen and instead resorts to running laps on his balcony. Two residents form a connection by pretending to be meticulous, notebook-toting super spies.

In the background of their whimsy and magic, we witness everyday survival and inevitably see our past selves in their ways of getting by. These children play games to pass the time, bang pots to celebrate health care workers, see their parents’ personal strife and help the best they can.

Despite being set during a time of intense fear and suffering, there is something inexplicably charming about this book and its players. Sunny Days Inside reaffirms our connection to one another, and captures a very specific period of time where our world became impossibly small, but we still managed to find wonder within it.

***

My daughter, now four years old, goes to a dance class every Saturday morning. Once taught beginner ballet via a laptop screen in our living room, she’s finally moved into the studio, wears a pink mask to match her pink tutu, and dances with her new friends six feet apart. Protocol insists we’re not allowed in the room during her lesson, but instead have to watch a line of children disappear down a hallway and reappear forty-five minutes later, bursting with excitement.

When I think back on that conversation with my neighbour, this Saturday morning dance class feels monumental. It feels like a brave step into risk, a victorious leap forward. It also feels like far too much weight to be put upon a child’s relatively minor (and long overdue) extracurricular activity.

Children are indeed resilient—they have proven this fact by surrendering so much, over and over again, in so many different ways. Sunny Days Inside perfectly captures a very specific moment where their strength and sacrifice were on display, showcasing that gift of finding genuine joy in the smallest things. But while the resilience is certainly worth celebrating, the thing that hurts, the thing that keeps so many of us up at night, is the fact that their resilience should never have been necessary in the first place.

Book Therapy is a monthly column about how books have the capacity to help, heal, and change our lives for the better.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Stacey May Fowles is an award-winning journalist, novelist, and essayist whose bylines include The Globe and Mail, The National Post, BuzzFeed, Elle, Toronto Life, The Walrus, Vice, Hazlitt, Quill and Quire, and others. She is the author of the bestselling non-fiction collection Baseball Life Advice (McClelland and Stewart), and the co-editor of the recent anthology Whatever Gets You Through (Greystone).