Fifth Business; First-Person Shooter - Whither the Great Video Game Adaptation?

By Evan Munday

When an author mentions a book adaptation, the next question the author fields is invariably about casting. The book adaptation is assumed to be a film or television series. After all, books have provided source material for filmic entertainment since the days of the Lumiere Brothers, and each year sees dozens of film adaptations of novels, nonfiction texts, short stories, and comic books. But rare is the literary video game adaptation.

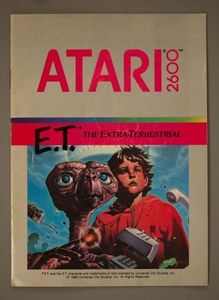

Video games, as an art form and industry, are no strangers to adapting other mediums. Many game enthusiasts will cite E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial, a largely detested Atari 2600 game from 1982, as an early example – one so heinous that the company buried 700,000 unsold cartridges in a New Mexico desert – but there were also early game adaptations of films like Tron and Fantastic Voyage. (There was even a 1976 arcade version of cult Roger Corman film Death Race 2000!)

Even corporate brands quickly got into gaming to spread their marketing messages, from Atari games like Kool-Aid Man and Pepsi Invaders, to later games for Nintendo like Yo! Noid (featuring the short-lived Domino’s mascot) and the infectious multi-platform Cool Spot (for 7-Up). One could even argue that music has been ‘adapted’ into video game form with the popularity of games like Guitar Hero, Rock Band, and the more questionable trailblazer, Revolution X (starring Aerosmith as kidnapped freedom fighters in a dystopian 1996 where ‘youth’ culture has been banned). Yet video game adaptations of books are rarer than a green 1-up mushroom.

There are, of course, exceptions. The most famous example is the video game of Dante’s Inferno, developed by Electronic Arts for the X-Box 360 and Playstation 3 (and soon to be required playing for all Medieval Lit majors). As in the epic poem, Dante descends into Hell, but unlike the text version, Dante is a Templar Knight, hacking and slashing both demons and the damned, in a quest to save his beloved Beatrice’s soul from Lucifer. (Why the game version Beatrice is in Hell, rather than Paradise, is a good question.)

There are a number of popular games that many gamers may not even be aware have books as their source materials. The popular Witcher game series is based on books by Andrzej Sapkowski and the Metro: 3033 series is inspired by novels by Dmitry Glukhovsky. The list of games based on written texts is short. Longer if you include the countless games based on comic books. But given that gaming has a proud history and tradition of text-based games like Zork and Adventureland, where are are all the games based on books?

It’s a valid question. As narrative game developer and author Kaitlin Tremblay (Ain’t No Place for a Hero, ECW Press) notes, “books, like video games, require carefully constructed worlds and universes, with starkly defined themes and atmospheres … World building is an integral part of narrative game construction.” (Perhaps this explains why there are, in fact, game adaptations of Frank Herbert’s Dune.) Literary agent and gamer, Kelvin Kong, agrees: “with a book, you have a developed setting, characters, plot lines – so much of the foundations are already laid. You’ll still need a writer to write the story and flesh out the world to fit the game, but it’s easier to fit a game into that established world.” Kong adds that if a book is already popular with readers, it also ensures some built-in buzz for the game adaptation. “If it’s a well known property, you’ll have more fans who are invested in it … you’ll have a segment of captured market.”

In a province like Ontario, which by most estimates accounts for 30% of Canada’’s gaming industry, there can even be economic advantages to adapting a book into a game – provided the author lives in Ontario. Manager of Industry Initiatives at the Ontario Media Development Corporation, Erin Creasey, notes the OMDC is committed to “enabling cross-sector collaboration across cultural media sectors,” including books and interactive digital media. “We work hard to create opportunities for Ontario content creators to meet and establish partnerships, through professional development and networking events like our Digital Dialogue Breakfasts, and events like From Page to Screen, where Ontario film and IDM producers meet with book publishers to learn about books they can option for screen-based development.”

There’s even a signature program, the IDM fund, that allows book and magazine publishers to submit projects for new presentations of their texts in interactive digital media. In theory, this fund could help fund future literary game adaptations: “Because book publishers are at the nexus of great storytelling, and are bringing so many interesting, diverse, and engaging characters into the world, the IDM Fund presents innovative ways to bring stories to light in new ways – be it through a game, an interactive storybook, or a web series.”

The fund has already been used to support a game adaptation of the TV show Orphan Black by local producation house Boat Rocker and the early-stage activities for the web series adaptation of Sara Taylor’s Boring Girls (ECW Press) by producers Coral Aiken and Hannah Cheeseman.

Books have the groundwork necessary for good game adaptation. The demographics of gaming (over 40% of gamers are women) and fiction reading (over 80% women) are converging. And there are even government initiatives to support literary game adaptation. Are we just a few years away from a Jane Austen dating sim? Maybe. Maybe not.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

For one, there is the issue of interactivity. Video games are all about changing the narrative – and a lot of classic fiction doesn’t lend itself well to readers rewriting the text. As Tremblay points out, “one of the excellent things the game industry is doing right now, especially indie games, is examining different viewpoints and filtering experiences through an explicitly interactive lens. What Remains of Edith Finch and Gone Home are both very successful indie games that explicitly tell stories through mechanics, through capitalizing on player interactivity, and what it means to have your audience controlling elements of your story. This isn't to say adaptations can't take advantage of this, but more to say there is a lot of original and creative work being done through thinking of stories intertwined with interactivity and game design.”

That said, she thinks we may see more book adaptations than we have been seeing: “The more diverse voices we bring into the game industry, with varied backgrounds and frames of reference, we'll end up seeing different books being adapted into video games.”

Kong is similarly ambivalent about literary video games’ future. “It’ll always be the genre books (sci-fi and fantasy), children’s books, and hot properties with large crossover appeal that’ll be picked first. It’s difficult to make a game out of a literary property – a literary setting is harder to build a game around.”

He does, however, foresee more interactivity in future novels. “I can see someone doing the transmedia thing and making a sort of visual novel (think Choose Your Own Adventure with more pictures), and maybe some sort of additional mechanic like resource building (big thing in Asia, becoming a bigger thing here in North America) out of a book, with the same characters, maybe different story.”

The other factor is that often the most creative game developers – the ones who could, say, turn the Dick Francis novels into a thrilling horse-race/puzzle game – are often working on their own brilliant and engrossing interactive stories that rival acclaimed works of fiction.

While it remains to be seen if games like Dante’s Inferno and S.T.A.L.K.E.R. (based on the Strugatskys’ novella Roadside Picnic) will be curious anomalies or leaders in a fruitful new genre, the elements and resources are there for a literary video game renaissance. But whether game makers and players are interested is – like most things in gaming – endlessly debatable.

FUTURE POSSIBLE CANLIT GAMES

Kait’s Idea:

I was going to say The Collected Works of Billy the Kid by Michael Ondaatje, but Call of Juarez: Gunslinger is already such a perfect video game example of what makes Collected Works so good: it's an interrogation of heroism in the Wild West through an unreliable narrator and historiographic metafiction. Otherwise, I'd love to create a narrative-driven, body horror adventure game based on The Tracey Fragments by Maureen Medved. The gameplay would echo the detective-like quality that Tracey embodies as she interrogates her own memories in order to form a complete picture of who she is and her trauma, having players discover bits about Tracey's character through vignettes and completing puzzles in a non-linear fashion.

Kelvin’s Idea:

Oh my god, maybe Publishing Tycoon. There’s a business simulation genre of game where it’s all about building a business and making decisions around it (logistics, marketing, etc). Those games have covered things like a lemonade stand, a farm, a prison, a theme park, and even the video game industry. No one’s done Publishing Tycoon and it would probably be a hilarious game to play. Like BookNet Canada’s Pubfight but with even more levers to pull.

How much office space will you devote to your publishing house? How much will you spend on this author’s tour? How nice will you be to this agent, which may decide how much they play hardball during negotiations? Will you spend an additional $50 per night for free drinks for the author and their mates? How big a stand will you rent for a book fair? How many nights do you stay at the fair? Maybe a little mini-game like an Arkanoid-type game that sets how easily you’ll fill out your grant applications, and the chances of the grant website crashing on you when you hit ‘submit.’ The game can be done in all pixel art so it’s funnier when the characters in the game constantly run around with little sweat drops popping out of them.

Or maybe an adventure game called CanLit that’s set in the woods somewhere, with a character living in a cabin to “find themselves,” and every day they go chop for wood (mini-game: press the correct sequence of keys displayed on the screen to match the rhythm, and you chop more wood), and at night, contemplate life (by clicking on various objects on the screen that will bring up more narrative). Oh man, everyone’s going to hate me for even coming up with that, aren’t they?

Other Free Ideas:

Fifteen Dogs (by André Alexis):

Choose one of fifteen playable breeds (poodle? Jack Russell?) and explore downtown Toronto, avoiding menacing fellow dogs, dangerous motor vehicles, and poisonous hot dogs in the Garden of Death in your quest to achieve happiness.

Shoeless Joe (by W. P. Kinsella):

A three-part game in which you, as Ray, must first successfully build a baseball diamond in your wheat field, Minecraft-style. Then, you must best the 1918 Chicago White Sox in a nine-inning game of baseball. And finally, you must, detective-style, track down J. D. Salinger. Three tasks, each more difficult than the last.

Brown Girl in the Ring (by Nalo Hopkinson):

As Ti-Jeanne, you must use your magic to protect your baby and Tony, the baby’s father, from gang leader Rudy, the duppies he has at his disposal, and the ruthless Premier of Ontario, who is on the hunt for a healthy human heart, in a dystopian Greater Toronto Area.

No Logo (by Naomi Klein):

A simple shooter reminiscent of Space Invaders, where the player (or adbuster) must destroy a seemingly unending supply of corporate brands before they overwhelm the gaming space.

They Left Us Everything (by Plum Johnston):

Roam the cityscape, as in Pokemon Go, collecting objects belonging to your dead parents and amassing the bittersweet memories that accompany each. When you max out your grief experience points, look for red wine to replenish your health.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Evan Munday is the author and illustrator of the acclaimed book series for young readers, The Dead Kid Detective Agency. Both The Dead Kid Detective Agencyand its sequel, Dial M for Morna, were nominated for the Silver Birch Fiction Award.

Evan has worked in book marketing and publicity for ten years, eight of which were as publicist at Coach House Books, and he has since worked as a freelance illustrator and ebook designer.

Find out more about Evan on his website, idontlikemundays.com or follow him on Twitter at @idontlikemunday.